Part One: Some of the amazing structures that used to stand in the city

HERE's a personal selection of twelve lost buildings of Manchester. There are many more where these came from.

These aren't necessarily the biggest lost buildings of Manchester - although there's a lot of that too, but they are representative of the various periods of Manchester's built history and its variety.

Assize Courts

Date: 1864

Architect: Alfred Waterhouse

Manchester Assize Courts on Bury New Road is acknowledged as one of the great 'lost' buildings of Britain. Alfred Waterhouse (architect of Manchester Town Hall, the main University of Manchester block and Strangeways Prison, which lies immediately behind the site of the Assize Courts) won the competition to design the building at the tender age of 29. His largely Venetian Gothic design popularised the style nationally.

The fantastical skyline of the buildings, the clever interior planning, the quality of finish and the rich detail in applied arts - the building was filled with sculpture for instance - all made it an immediate hit. The main criminal and civil courts could hold 800 people each and were spectacular, see the main image at the top of this page.

Heavily damaged in World War II this stunning building was demolished while other shattered buildings such as the Free Trade Hall were restored and re-opened. It was a terrible shame.

Demolished or destroyed: 1957 (after standing empty and gutted for 17 years following WWII bomb damage)

Bernard House, Piccadilly Plaza

Date: 1965

Architect: Covell, Matthews and Partners

Yeah, yeah I know what you're saying, how can I include this? The vast, futuristic (when it went up) Piccadilly Plaza quickly moved from exciting the Manchester public to annoying them as the upkeep of the vast structure lapsed and the concrete became increasingly stained.

Still, most of Piccadilly Plaza survives when so much concrete Brutalism of the sixties has been dropped. Unfortunately Bernard House, in many respects the liveliest element of the whole ensemble, was the part sacrificed in 2001. Thus Manchester lost that crazy roofline that curved up and stabbed out like a fancy dress hat.

Technically Bernard House has been described like this: 'The building, a popular landmark in the centre of Manchester, has a unique roof which makes it a striking feature of the skyline. It is a timber structure of hyperbolic paraboloid form, comprising of a main rib element on each of the four axes of twin Glulam Beams.' Curiously that loving description came from the demolition contractors. Did they feel guilty?

The replacement by Leslie Jones Architects brings shame on them. How could they have designed this bland, grey, sub-trading estate building for this key site? The person who came up with it should be made to run naked around Piccadilly Gardens once year as an example to other architects. What an idiot. What an example to cities of 'be careful what you wish for'.

Demolished or destroyed: 2001

Botanical Gardens and Palm House

Date: 1854

Architect: Thomas Worthington

I love the look of this daft palm house by Thomas Worthington, designer also of Albert's Chop House (originally The Memorial Hall), Withington Hospital and many other Manchester buildings plus the Albert Memorial itself in Albert Square.

The sixteen acre Botanical Gardens at Old Trafford, the site of the Manchester Royal Jubiliee Exhibition (see separate entry below) was apparently superb, a well-tended flower filled haven for Mancunians and visitors that was stuffed with exotica too. As Manchester lacks a proper botanical gardens, unlike most other major European cities, we could do with it back.

The gardens got into financial difficulties in the 1880s. As the archives of the Royal Botanical and Horticultural Society of Manchester reports: 'Wealthy Mancunians had moved out of the city to the suburbs and to outlying villages such as Didsbury, Bowdon and Alderley Edge, where they could indulge their horticultural interests in their own extensive gardens. By the end of the 19th century interest in the Old Trafford Gardens had declined steeply. After attempts to persuade Stretford District Council and Manchester City Council to purchase the Gardens had proved unsuccessful, in 1907 the site was leased to the White City Limited, part of which was to be used as an amusement park.'

The amusement park became a dog track and then White City Retail Park. The entrance to the Botanical Gardens has been preserved on Chester Road.

Demolished or destroyed: 1907 or shortly after

Dr Charles White's House

Date: Early 1700s

Architect: Unknown

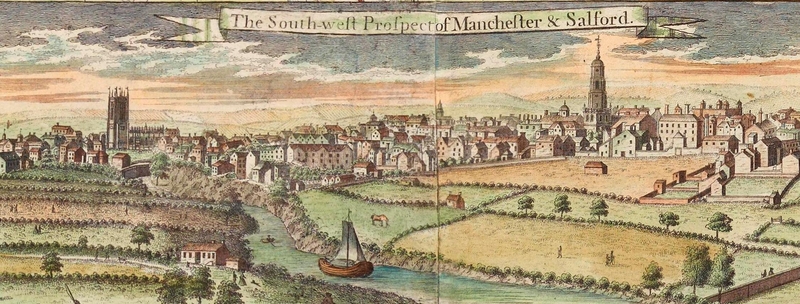

The junction of King Street and Cross Street once contained a beautifully harmonius range of buildings propped up on an arcade of Doric columns.

These buildings are included for their charm. We still carry many traces of early Manchester in the city centre but this range provided perhaps the sweetest collection of domestic architecture. Remember before the industrial revolution changed everything Manchester was a famously handsome town of good-looking buildings (Think Ludlow or Kirby Lonsdale) and interesting personalities.

The main house shown here was owned and run as a surgery by Dr Charles White. This man was a 'brain' and a founder of Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, the oldest surviving society of its nature in the kingdom, and an institution that has made a remarkable contribution to science and medicine. He also helped establish Manchester Infirmary and later St Mary's Hospital. He was a pioneer in obstetrics.

Presently 53 King Street offices (a conversion of a former Lloyd's Bank) occupies the site, a very handsome structure in its own right and designed by the prolific late nineteenth, early twentieth century architect, Charles Heathcote.

In between the house and the bank the site was occupied by the original Manchester Town Hall.

Demolished or destroyed: 1821

The Hippodrome

Date: 1904

Architect: Frank Matcham

Frank Matcham, aka 'Matchless Matcham', was one of the world's great theatre designers a hundred years ago. His buildings were essays in escapism, palaces within which people could lose themselves in the bright lights and the fantasy of music and performance. Blackpool Tower Ballroom, The London Palladium, even County Arcade, Leeds, (flexible chap, our Frank) are his. But The Hippodrome on Oxford Road was something else.

'It was a tour-de-force of theatrical architecture. The principal entrance was through a colonnade, approached by marble steps. Walls, staircases, balustrades were also marble. The architecture was Arabesque style. Hidden from the audience beneath the auditorium was stabling for one hundred horses and a lion's den.'

The present flamboyance we see in the Palace Theatre and the Opera House in Manchester was far exceeded by The Hippodrome. It's a crying shame that no pictures of the interior remain - unless someone can tell me differently.

The venue held 3,000 people in comfort and was capable of putting on music hall, circus and water spectaculars as well as regular theatre. Performers who strutted its boards included Sarah Bernhardt, Ellen Terry, Lily Langtree, Pavlova, Gracie Fields and George Formby. According to Terry Wyke's superb Manchester Theatres book Formby 'was so fond of the theatre that a reproduction of the proscenium arch was placed over his grave' during his funeral.

By the 1930s the writing was on the wall for these vast live performance spaces, cinema was all the rage. In 1935 the Hippodrome was demolished and the Gaumont cinema built, another 'lost building' for a later column.

Demolished or destroyed: 1935

General Post Office

Date: 1887

Architect: J Williams

Nikolaus Pevsner, the famous architectural critic of the 1960s, in his 'Buildings of England' series, wrote this: 'Doomed to disappear. It was a tremendous palazzaccio, like Ministry building in Rome'. Its 1969 replacement by Cruickshank and Seward reveals the International Modern style's frequent failure in tight urban corners.

The General Post Office is truly one of our great losses.

It was a monumental block yet one that still talked to the street. That was its skill.

Behind the grand upper portico were generous spaces and elegant halls that made the act of communication seem heroic. A sculpture once housed in the building and shown in the interior picture below is now located outside the Oldham Road sorting office.

Demolished or destroyed: 1968

Heaton Park bandstand

Date: 1906

Architect: unknown, possibly the city architect Henry Price

When the Heaton Park bandstand was built it was called a 'curious structure' by the Manchester Guardian. It was a bit mad but it was magnificent as well, more an outdoor stage under a proscenium arch as in any proper theatre rather than a mere bandstand. It can claim to hosting Manchester's first DJ as well.

William Grimshaw, from nearby Prestwich, was a bicycle retailer on Bury New Road. He loved music too and expanded his nascent empire with the brand new technology of the day, the gramophone. In a single leap he became the UK’s first superstar DJ playing to vast crowds in Heaton Park.

This followed a visit by Grimshaw to the Free Trade Hall on 13 September, 1909, and a concert by the famous tenor Enrique Caruso. Grimshaw was deeply moved. So much so, he got hold of a huge gramophone and took it off to the great bandstand of Heaton Park, not so far from his shop, and let the needle work its magic blasting out the ‘charm and power’ of Caruso.

The local papers reported how trams to Heaton Park became filled and queues formed at stops all along the rail line between Manchester and Bury. It was reported a crowd of 40,000 gathered in their best outfits to listen to the concerts, and, ‘they remained as if spellbound from the moment of arrival to the close of the programme, which, it is hardly necessary to say, was intensely enjoyed.’

Caruso became aware of the concerts and wrote to Grimshaw to say thanks at the way his reproduced voice had been given an extended audience through the magic of the gramophone. It’s interesting he didn’t also have his agent contact Grimshaw and demand a royalty, and amusing that without being asked Caruso included a signed cartoon of himself.

Demolished: by the 1960s

Kardomah Café

Date: 1939

Architect: Misha Black

The Market Street Kardomah café was one of the smoothest and loveliest internal fit-outs in the city’s history. Inserted inside a Victorian building, it's entrance was also transformed into one of the slickest of external designs, especially at night when it shone like a Modernist jewel.

The Kardomah was designed by Misha Black (1910-1977). Black was born in Azerbaijan and came to England at the age of two. He began designing posters at the age of 17 and in 1934 joined the Bassett-Gray design consultancy, later named the Industrial Design Partnership. During this period, he contributed to designs for a number of exhibitions including the interior for the British Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

He also designed various Kardomah’s including this delicious sweetheart on Market Street in the Streamline Moderne style. It was completed in 1939. The interior featured a glorious, sweeping, feminine staircase as smooth, in this golden age of Hollywood, as Dorothy Lamour’s complexion. There was a mural on the wall and gleaming tables and polished wooden fittings. The Market Street Kardomah (there were several Kardomah’s in Manchester although this was the best designed) was the place to see and be seen on the city’s busiest shopping street, a futuristic promise of a hi-tech, cleaner world, with, as people said back then, ‘all the mod-cons’.

The Kardomah on Market Street is featured in novels and books by two of Manchester’s literary giants, Anthony Burgess and Howard Jacobson.

As fashions changed and as Market Street became a retail desert rather than a street with shops, pubs and cafes, the Kardomah closed and that lovely interior was ripped out, gone by the 1970s, a sad loss on a street that could really do with it back.

Demolished or destroyed: 1970s

Manchester General Cemetery Gates

Date: 1837

Architect: William Lambie Moffat

There's something very evocative about Manchester General Cemetery in Harpurhey. On the little hill above the steep drop to the River Irk Valley the tombs clump and gather like a mini-Mancunian Highgate Cemetery.

But something major is missing from the entrance on Rochdale Road.

The gateway and side chapels from the 1830s were the finest neo-Greek buildings in the Manchester area. As good as the Art Gallery, as austerely powerful and exquisitely modelled as The Oratory in Liverpool.

Why they had to go is now lost in council records from the post-War period. Probably something sneary to do with them being old-fashioned and impractical for the modern age: the snears excusing and disguising a cost-cutting, penny pinching attitude and an astonishing lack of vision.

This magnificent set piece architecture by Moffatt would now be a source of pride for North Manchester, somewhere for people to visit - instead we have a low wall where the buildings once stood.

In a way these chapels and gate are Manchester's Euston Arch.

Demolished or destroyed: Early sixties

Manchester Royal Jubilee Exhibition Building

Date: 1887

Architect: Maxwell and Tuke (also architects of Blackpool Tower)

This building was constructed for the Manchester Royal Jubilee Exhibition of 1887. It had a dome 150 feet high - almost as wide as St Paul's dome - and murals by renowned artist Ford Madox Brown. Brown, during the same period, was painting his celebrated set of murals in Manchester Town Hall. Next to the main building at the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, there was a re-creation of 'Old Manchester', in otherwords a sort of proto theme park.

The Exhibition was a total success with more than 4m people visiting the event in its 192 days of operation. It provided a showcase for Manchester and its region contained within a 300ft main chamber opening into lots of side rooms. There was a 32ft long model of the route of Manchester Ship Canal for which the exhibition operated as a fund-raiser - the first sod of the Canal was cut the day after the Exhibition closed.

On the opening of the Exhibition in 1887 the Lord Mayor WH Bailey had said: 'If when the Exhibition terminates it should be the good fortune of the Executive Committee to have a surplus, it may not be an improper thing to indulge a hope that some portion...of the profits may be used to promote technical education and that as a survival we may have a permanent Exhibition in the interests of utility and beauty'.

Demolished or destroyed: 1888

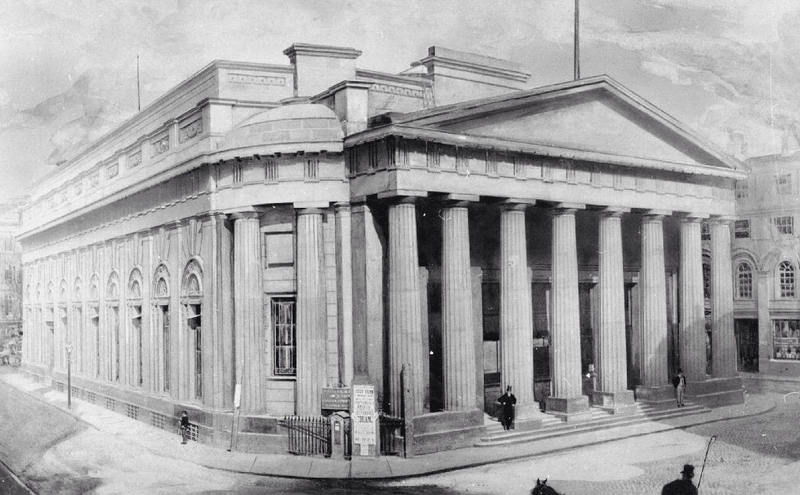

The Royal Exchange - third building, first stage

Date: 1864

Architect: Mills and Murgatroyd

The first exchange in Manchester was a humble but handsome affair of 1729 where Marks & Spencer, Market Street, now stands. It was replaced in 1809 on the present site, and then enlarged by Alex Mills in 1849. This was the most elegant of the Exchanges which by the latter date was the most important textile Exchange in the world.

More room was needed a few decades later and this was delivered by Mills and Murgatroyd in 1874. Suddenly Manchester had one of those heart-stoppingly epic giant order classical porticos that always add power and authority to any street scene.

By World War One optimism about on-going trade (total production in UK of finished cotton through the Royal Exchange 6.6bn linear yards, nearest rival Japan, 56m linear yards) meant another extension. This resulted by 1921 in the building we see today.

To extract every scrap of available space, the grand portico was demolished and the building pushed out to the pavement line. Thus Cross Street lost its stop-in-the-street-and-stare architectural motif.

Demolished or destroyed: 1917

York House, Major Street

Date: 1911

Architect: Harry S Fairhurst

This building was a textile warehouse designed by Harry S Fairhurst, a prolific architect in the first years of the 20th century, Lancaster House, Ship Canal House and many other buildings are his work.

York House shows his skill in extracting the best he can from awkward sites.

Nice car park isn't it? The back of the building is as faceted as cut diamonds, with glazing stepped back to bring in as much light as possible.

In the sixties Manchester decided the modern thing in the sixties was an inner ring road like Birmingham's. This a huge swathe of warehouse Manchester was condemned.

But people admired York House and its anticipation of much of what was standard in the modern architecture of its day.

Campaigns were launched, the university wanted to step in, Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius commented, there was even a 1968 modernist exhibition in New York's MOMA which underlined the value of York House.

But the council and the planners weren't to be thwarted and York House was demolished. The sad, almost hilarious, irony is that instead of a sleek throughfare, the money ran out and we have the very opposite of a road where York House once stood. We have a car park.

Demolished or destroyed: 1974

This is a republised and repurposed article from the archive. The buildings are also featured in Jonathan Schofield's books, Lost & Imagined Manchester and Illusion & Change Manchester (£16.99) - they can be bought here. Or you might want to attend one of his regular tours. You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter and Instagram on @jonathschofield

Also read:

The story of Manchester architecture: Part one

The story of Manchester architecture: Part two 1800-1850

The story of Manchester architecture: Part three 1850-1894

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!