Jonathan Schofield continues his online tour with the city's defining building type

THE nineteenth century is perhaps the century that seems to define – in the popular mind anyway - Manchester's architecture. This was the age of the triumph of cotton, the making of British engineering, the century where the great urban/rural population shift took place. Here, we look at the first 50 years of the century.

If you walk among these buildings, recall when you have been on your own travels around the world and felt utterly overwhelmed

This was Manchester for the world...

Let's start with a completely new form of building: the factory. More pertinently for Manchester, the cotton factory, especially in Ancoats and Chorlton-on-Medlock. This was the Mancunian building form that chiselled itself into the imagination of the world. These buildings put the ‘shock’ into the expression ‘the shock city of the age.’ To visitors the scale of the new industrial processes was beyond their range of experience. ‘Here are buildings seven to eight storeys, as high and as big as the Royal Palace in Berlin,’ said the German architect Schinkel in 1825, who couldn’t believe they were factories working night and day.

The mills dramatically underlined how a change had taken place that would eventually transform the globe. For some like future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, it was exciting, ‘a new world, pregnant with new ideas, and suggestive of new trains of thought and feeling,’ for others such as French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville it was terrifying. ‘Everything in the exterior appearance attests the individual powers of Man: nothing the directing powers of Society.’

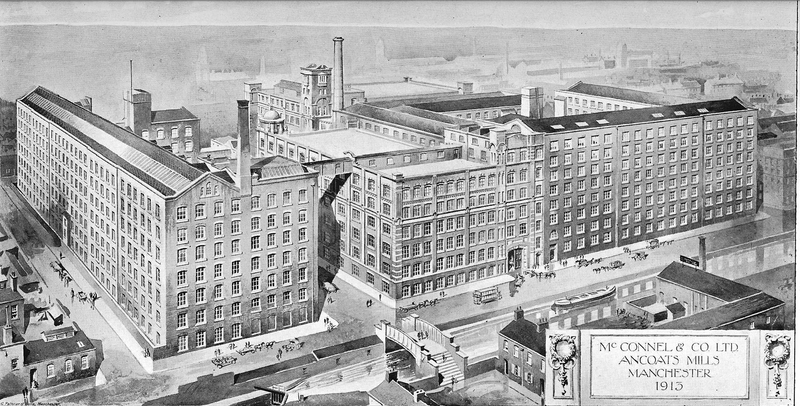

Superb, impressive and exhilarating examples of factories remain in Ancoats with Murray’s Mill, the McConnel & Kennedy complex (including Royal and Sedgewick mill). These have been splendidly restored and cover all the dates of mill development from 1798 until the 1920s. Similarly excellent examples are Chatham Mill, Chorlton New Mills and Macintosh Works in Chorlton-on-Medlock.

If you walk among these buildings, recall when you have been on your own travels around the world and felt utterly overwhelmed by the buildings around you. If you can do that, you will re-capture something of the impact of these structures.

Other industrial buildings of the period are all about infrastructure, whether it’s Benjamin Outram’s skewed (crossing the road at an angle) Store Street Aqueduct for the Ashton Canal, 1798, or the similarly ground-breaking Stephenson Viaduct from 1830, between Castlefield and Ordsall, by George Stephenson for the first true passenger railway system, the Liverpool to Manchester Railway (LMR).

Speaking of the LMR, the Liverpool Road Station building is revealing. This first station doesn’t look like what we came to know as the ‘station-look,’ big iron engine sheds, grand facades and all that. This was because the designers had no idea how a railway station was supposed to look. The result is essentially a building that resembles a terraced row of townhouses.

Indeed, in genteel domestic architecture, in the first half of the nineteenth century, adaptations of the late 1700s townhouse remained the norm. For workers in the new factories regiments of decoration-free, purely functional terraces became the norm. They were beyond grim. The ‘Coronation Street’ model was born, although the later terraces, such as Coronation Street, were big improvements on the first examples.

Gothic makes a return

Now, to churches. In the first part of the nineteenth century the fashion had returned to the Gothic style, but to begin with only as a species of Gothic dreamed up in the architects’ heads without the principles developed in true medieval buildings - it was a period of time that also led to the Gothic novel such as Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. In this instance Gothic was spelt Gothick and was great fun, and is still with us in a zillion TV series and films.

Gothic with its soaring vaults and pointed arches, its spires and pinnacles, appealed because it felt more emotional and human, less coldly rational than the severe disciplines of Classical architecture.

Charles Barry’s All Saints (1826) at Stand near Whitefield, with its tall, Gothic-horror porch, is a classic example. It’s a scandal that Barry’s glorious St Matthew’s Church in Castlefield was demolished as late as the 1950s. Barry crops up again in this section and would later rebuild the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) into every tourist's favourite photo opportunity in London. Another fine example in the city is the more restrained St George's in Castlefield/Hulme by Francis Goodwin – now apartments.

A crucial building nationally is the much messed about with St Wilfred RC (1842) in Hulme by AWN Pugin. This was one of the first ‘archaeological’ churches, harking back to the principles of the Middle Ages. It was a bit dull but it was ground-breaking. After it, everything with churches had to be done correctly according to the dictates of true Gothic architecture and the various accepted styles within the canon: Early English, Geometrical, Decorated and Perpendicular. A beautiful example of the new mood of architecturally correct churches is the stunning St Mark's, Worsley, from 1846 by George Gilbert Scott.

A curiosity is Edmund Sharpe’s church, Holy Trinity, Rusholme, (1845) built entirely out of terracotta in the Decorated style. It’s lovely but also a huge advertisement for his brother-in-law, John Fletcher. The latter owned collieries in Bolton and had access, next to his coal seams, of good fireclay which is used for the making of tile. In effect the church is a billboard saying 'use terracotta, look you can build whole buildings with it.'

Gothic was making an impact with institutions. The Lancashire Independent College, on College Road, is a striking survivor, with its impressive facade. It’s by Irwin & Chester from 1843 and is now the British Muslim Heritage Centre. It’s a crying shame that Richard Lane’s Henshaw’s Blind Asylum was knocked down in 1972. This 1837 building had a thrilling facade. The site in Old Trafford is now a rubble-strewn wasteland.

There’ll be a lot more about Gothic in the next chapter of this architectural story.

Here come the Greeks and the Italians

Another prominent style was Greek Revival in the early part of the nineteenth century.

Travellers were discovering the purities of original Ancient Greek architecture, particularly as the Ottoman Empire in the eastern Mediterranean declined. Previously the Roman interpretation of Classical architecture had been the big influence.

Thomas Harrison was one of the first to bring the Greek Revival to the city with the Portico Library (1806) whilst Charles Barry added the grandest of these buildings with what is now Manchester Art Gallery. Barry’s motto for the building was 'Nihil Pulchrum Nisi Utile' – nothing beautiful unless useful, a very Manchester sentiment, easily as good as the more recent strapline by Peter Saville of ‘Original Modern.’ The powerful simplicity of the portico with its bold Doric columns in the centre, balanced by the symmetry of the wings, shows how so much of Greek Revival architecture was about the 'massing' of the building - the way the overall shape of the structure holds together. The main picture, above, is of the Art Gallery.

The most individual take on this style was Charles Cockerell’s Bank of England (1845), now offices on King Street. Across Pall Mall, also on King Street, we have Richard Lane’s former Manchester & Salford bank (1842) which is similarly Greek inspired. It’s Lane’s Town Hall’s for Chorlton-on-Medlock, Grosvenor Street, All Saints, and Salford, Bexley Square, plus his Friend’s Meeting House on Mount Street, which really underline his use of the simplicity and power of the Greek Revival.

But we have to return to Charles Barry for a real game-changer, and one that would prove to be an inspirational building. This was the Athenaeum from 1837, for a society devoted to arts and learning. Barry based his design on Italian Renaissance palaces. The dignified, grand appearance was adopted by cotton barons as the style of choice for their warehouses. The so-called ‘Manchester Palazzo’ had arrived, more of that in the next chapter. The Athenaeum is now part of Manchester Art Gallery.

The final building in this section is one of the best examples of the ‘palazzo’ style and that’s John Gregan’s elegant Heywood’s Bank from 1848 on St Ann’s Street. It’s now the Royal Bank of Scotland and is a delight, perfectly proportioned, with lovely stonework, sweetly attached to the former bank manager’s house, largely made of brick.

Not everything has to be grand in architecture and this modestly scaled building is one of the best in all the city’s history.

Jonathan Schofield offers regular tours of the city. Gift vouchers can be purchased for the second half of 2020. The tours cover a huge range of themes and topics - here's a list. With every voucher people receive a daily weekday gift. Gift vouchers can be purchased via this link.