Jonathan Schofield and the battle of the styles

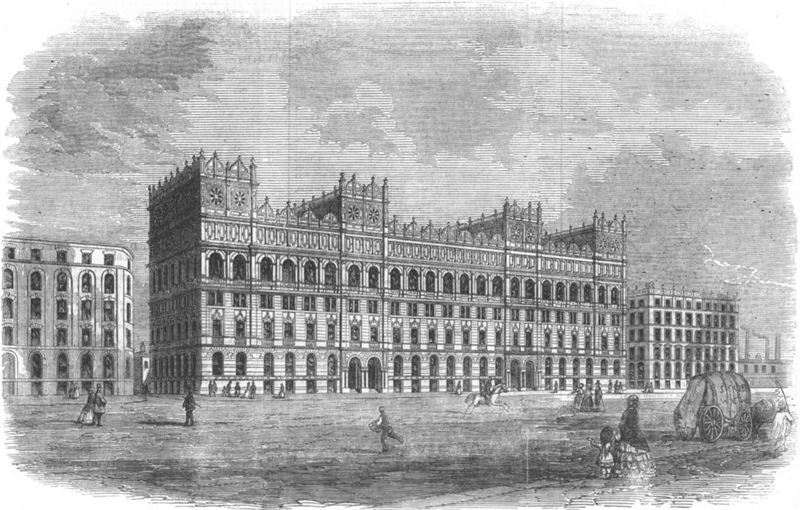

We finished off the last chapter with the creation of the ‘Manchester palazzo’ style by Charles Barry and we need to continue with it a little longer. In that instance we talked about a club, The Athenaeum, where it began, and Gregan’s beautiful bank on St Ann’s Street. However perhaps the most pertinent given Manchester’s trading status was the use of the model in textile warehouses.

Whether you look at the proportions outside or the internal decorations… there is nothing like it… in any part of Europe

The simple but stately design of the Renaissance model allowed plenty of light into buildings whilst not wasting too much space on decoration. The main salesrooms with cotton samples were on the upper floors, the first floor provided the counting house and the administration, whilst the lower basement contained the machinery, the steam engines and the boilers. A large iron gateway led from the rear or side through which laden cotton carts left. The heavy carts cracked stone kerbs so iron kerbs are a feature in Manchester streets, especially in the warehouse areas.

This picture below shows one of the elegant Princess Street buildings by Clegg and Knowles, 1869. As C.R. Reilly (1924), described: ‘(the) warehouses represent the essentials of her trade, the very reason for her existence. They are too near to her heart, for any light treatment. Hence their simplicity, strength, and sincerity, and consequently their real beauty.’

Much of central Manchester is still defined by warehouse architecture from the Northern Quarter down Mosley Street, Portland Street and Whitworth Street to and including Oxford Street and Great Bridgewater Street.

The ‘palazzo,’ as with all art and architectural fashions, was never a pure ideal and often was simply a frame from which to hang off a variety of designs: an essay in showmanship. This led to remarkable structures such as Travis and Magnall’s Watt's Warehouse (1858), now the Britannia Hotel, the greatest in scale of the textile warehouses occupied by a single company and a cocktail of architectural styles including Italian, French, Elizabethan and even Egyptian motifs. The present occupant, the seedy Britannia hotel doesn't do it any favours, but an idea of the ebullience of the Manchester cottontots (the nickname for the textile millionaires) is in evidence with the gorgeous grand staircase that climbs, turns and then rises over itself in a series of Venetian bridges.

Edward Walters was a fine ‘palazzo’ architect, building some lovely warehouses on Portland Street and Charlotte Street but we leave warehouses again for his two best ‘palazzos.’ His masterpiece was the Free Trade Hall (1856), the main façade of which survives in the Edwardian Hotel. The balance and grace of this building have rarely been equalled in the city. The Manchester and Salford Bank (1860), now the Royal Bank of Scotland, on Mosley Street, isn’t far behind but here there’s more commercial bombast.

By the late 1850s Manchester had changed completely from the place it had been in 1800, even 1840. Industry had already arrived by 1800 but it was still recognisably a town of the eighteenth century – it was still a product of the old ways. By 1850 Manchester could not have been confused for anywhere else, in effect it was a city state - confident of its place in the world and attempting to control its own destiny.

The change is graphically illustrated in William Wyld's 1852 painting Manchester from Kersal Moor, where the foreground shows a traditional English country scene but the background is Manchester and Salford and a world changed with the old ways scorched away in the furnace of industry.

The sense of city confidence and pride in its position was reflected in the pioneering Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, the first major temporary blockbuster art show and arguably still the biggest ever, with 16,000 works placed in an exhibition hall in Old Trafford.

The pride was also reflected in the architectural practices. Manchester begins to get dynasties of designers. The most prominent nationally was that begun by Alfred Waterhouse and continued by his sons (although Waterhouse did decamp to London). In 1859, at the age of 29, the Liverpool-born, Manchester-trained architect won the commission to build the Assize Courts in the city. This essay in modern Gothic was a total success. The Courts were sadly demolished after bomb damage during WWII. It was followed by Manchester Town Hall (1877) – described as ‘a classic of its age’ - and the Victoria University (1887), now the University of Manchester, both in Gothic plus numerous other buildings.

Manchester Town Hall remains the poster-boy of the city's Victorian architecture, it is a candidate for the Victorian building par excellence – the whole age summed up in one: the extravagance, the energy, the self-belief and the achievement.

At the opening banquet in 1877, MP John Bright described the way the city felt about the new building: "With regard to this edifice, it is truly a municipal palace. Whether you look at the proportions outside or the internal decorations… there is nothing like it… in any part of Europe."

The main picture at the top of the page is of the Great Hall in Manchester Town Hall.

Waterhouse’s contemporary was Thomas Worthington who began a practice which still survives in the city. His contribution straddles both buildings and monuments in a variety of Gothic styles such as the Albert Memorial (1862), the Memorial Hall (1866) and the City Police and Sessions Court (1875), Minshull Street, now Crown Courts.

The middle years of the nineteenth century have been called the Battle of the Styles in Britain, an often passionate debate between those who favoured Gothic architecture and those who favoured the Classical, and its various offshoots. In public buildings in Manchester, unlike in Liverpool, the Gothic boxed the ears of Classical.

No doubt the new money industrialists and businessmen found it warmer and more charming than the colder purities of the other style. Edward Salomans, Manchester’s most prominent Jewish architect (who had designed the Art Treasures building pictured above), must have felt the same, or at least his clients did. His best building the Reform Club (1871) is in splendid Venetian Gothic. Gothic still cast a shadow over the end of the century when Basil Champneys designed the last great flowering of Gothic in the UK with John Ryland’s Library (opened 1900), a tour-de-force in red sandstone.

This extravagant building is a virtuoso performance in Gothic, capturing again some of the freedom and flair of the Gothick buildings of the early part of the nineteenth century (see chapter two) within, of course, a scholarly discipline. John Rylands Library is the firework display at the end of the whole British neo-Gothic revival. It's an astonishing way to bow out.

Manchester Ship Canal had opened in 1894 and with a general upturn in business a building boom hit Manchester. The steel framed building hit the city at the same time. The buildings in the late 1890s until the outbreak of WWI in 1914 are some of the most bombastic in the city. We’ll cover the years from the Ship Canal opening and also take a look at what was happening in domestic architecture and planning in the next chapter.

Jonathan Schofield offers regular tours of the city. Gift vouchers can be purchased for the second half of 2020. With every voucher people receive a daily weekday gift. AND NOW there are Zoom tours including one looking specifically at architecture. These are witty, fact-filled and allows you to see the city from your sofa. For more details click here.