Jonathan Schofield talks us through some of the characters we pass almost every day

Yesterday, we published an article examining why removing the statue of Robert Peel in Piccadilly Gardens is not a sound idea.

If we are talking specifically about slavery, few of the old Victorians in Manchester could be said to be directly tarnished. These include John Bright, Richard Cobden, Abraham Lincoln, Bishop Fraser, Prince Albert, James Watt, John Dalton and Joseph Brotherton.

Of course this is not to say they didn’t have aspects of their lives that might be judged ill by many today.

The tentacles of that trade in our fellow humans reaches out from the past into a bewildering number of nooks and crannies

The Duke of Wellington in Piccadilly Gardens was a soldier and later a deeply unpleasant Prime Minister. He extended British rule in India, which might condemn him as an Empire builder, but he was no slaver.

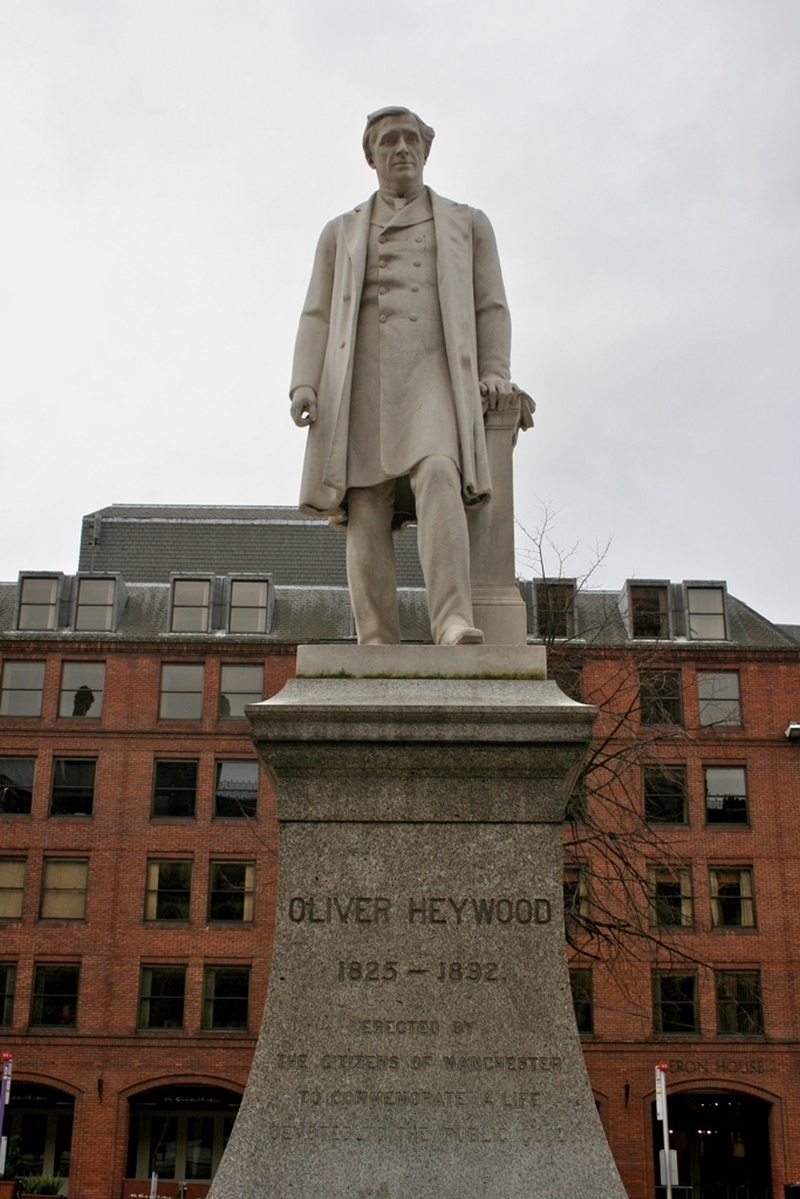

There are two much more problematic statues. Oliver Heywood, born 1825, who has a statue in Albert Square, was one of the great Manchester philanthropists, and again might be judged by the sins of the father or, in his case, the grandfather, if people want to strain for attributing guilt. The grandfather, Benjamin Heywood, had been part of a partnership which traded in African slaves from Liverpool and was involved in 133 slave ship voyages.

By the 1780s the Heywoods had settled in Manchester and set up a banking business. Their ties with slavery were cut. Oliver’s dad, Benjamin, who joined the bank in 1814, was an abolitionist. Indeed the father and the son were great supporters of workers’ education and generous donors to all manner of worthy causes. Yet there is no doubt that the money behind the initial setting up of Heywood’s Bank had blood on its hands.

The link with slavery and William Gladstone is much clearer, but the failing again lies with a relation, his father, not he. His statue stands next to Oliver Heywood’s in Albert Square. Gladstone’s father John was a Scot who moved to Liverpool with his wife as he saw great wealth could be made in the city as a merchant. To this end he acquired plantations in Jamaica and British Guyana and he kept on acquiring them until he became one of the world’s largest slave-owners. He held 1309 slaves in British Guyana alone.

By the 1830s the demand for the abolition of slave labour in the British Empire was growing (the trade had been abolished in 1807). Liverpool-born William, in his maiden speech as an MP in 1833, the year of abolition, did not defend the institution of slavery but was hardly loud in his condemnation of the vile practice. Worse, he argued that plantation owners such as his father should be given a fair deal in compensation.

His daddy got a very fair deal - the largest pay-out of all, £93,526. This (according to the money converter I used) would be over £10m today. Having a father with that amount of capital behind him was a leg-up for the young politician. By the end of his life, the four-time UK Prime Minister was GOM, the Grand Old Man of Liberal politics. And, since Manchester was a liberal city, he was honoured with a statue in Albert Square.

By then his connection with slavery had been conveniently forgotten; instead his reputation of standing for reform and progress, for promoting Irish Home Rule, the widening of the franchise and fair conditions for workers were emphasised.

He had certainly become forcefully anti-slavery himself by 1850, when he gave a speech in the House of Commons. He said: "With regard to the slave trade, I can find no word sufficiently strong to characterise its enormous iniquity. I believe the slave trade be by far the foulest crime that taints the history of mankind in any Christian or pagan country."

Back to Heywood.

It’s the ripples that spread from slavery and the money it made that makes the whole issue so complicated. Heywood’s Bank was acquired by the Manchester & Salford Bank, then William Deacon’s Bank and then the Royal Bank of Scotland which, of course, still exists.

Meanwhile Benjamin Heywood had been a founder of the Mechanics Institute in 1824 to assist workers gain new skills. The Mechanics Institute is the ancestor of the Technical School, which became the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology which merged with the Victoria University of Manchester to become the present University of Manchester in 2004.

So, the logo of the university bears the date 1824, the founding of the Mechanics Institute, which was undoubtedly a good thing, but was partly set up by money from Benjamin Heywood who owned a bank which had been set up with money which had been involved with slavery. More, the People’s History Museum, a museum dedicated to social justice and equality, rents part of the Mechanics Institute on Princess Street and was once located there.

So it could be argued that the Royal Bank of Scotland, the University and the People’s History Museum all have the blood curse of slavery.

The tentacles of that trade in our fellow humans reaches out from the past into a bewildering number of nooks and crannies. Yet, of course, it would seem that by any measure both Oliver Heywood and his father Benjamin Heywood were good and kind men. The fact their ancestor, that other Benjamin, felt it right to make money through human misery and bondage condemns him but does not change the fact that his descendants were different.