Jonathan Schofield continues his Manchester history series with stories from the 18th and 19th centuries

On 28 October 1787, Thomas Clarkson, a man committed to the abolition of the Africa slave trade, gave a sermon in what is now Manchester Cathedral. This is an account from his book, The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament, published in 1808.

‘When I went into the church it was so full that I could scarcely get to my place; for notice had been publicly given, that such a discourse would be delivered. I was surprised also to find a great crowd of black people standing round the pulpit. There might be forty or fifty of them. The text that I took was the following: Thou shalt not oppress a stranger, for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt’.

During his sermon Clarkson said: ‘If, then, we oppress the stranger, and if, we find that he is a person of the same passions and feelings as ourselves, we are certainly breaking, by means of the prosecution of the slave-trade, that fundamental principle of Christianity, which says, that we shall not do that unto another, which we wish should not be done unto ourselves. We come into the temple of God; we fall prostrate before him; we pray to him, that he will have mercy upon us. But how shall he have mercy upon us, who have had no mercy upon others! How shall he deliver us from evil, who are daily invading the right of the injured African, and heaping misery on his head!’

Clarkson was part of a growing campaign involved in removing the stain of the slave trade. Other famous campaigners included William Wilberforce. It was Clarkson’s decision to discover the dreadful facts of the trade by visiting the slaving ports of the UK that provided clear and terrible evidence for the abolition of the trade. This happened in 1807, although possession of slaves in the British Empire wasn’t abolished until 1833. Prior to visiting Manchester Clarkson had visited Liverpool where he’d received numerous death threats, before escaping an actual attempt on his life.

This first petition organised through brave radicals such as Mr Walker, Mr Phillips and Mr Bayley, was signed by more than 10,000 people, close to half the adult population of the town at the time. It was a proud moment for burgeoning Manchester.

The American Civil War starved Lancashire and it was the Union's fault

The anti-slavery campaigns in Manchester continued through the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 long into the 19th century. There was an inherent contradiction in this, an in-built hypocrisy, as from shortly after Thomas Clarkson's sermon slave-picked cotton started to feed Manchester's mills. So while many of the abolitionist mill-owners wanted slaves liberated in the southern states of the USA they still sourced raw cotton from people who kept other humans as chattels, brutally so. Of course, not everybody who supported abolition were mill-owners.

This uncomfortable hypocrisy is part of the story. So while families in the area are only in very very rare occasions slave-owners, Gregs of Styal for instance, much of the textile wealth produced in the area was underpinned by slave-picked cotton.

Black campaigners played their part too, let's not fall into the danger of thinking this was just a worried whites in the side of this Manchester story. Major and important visits from Frederick Douglass and Sarah Parker Remond reinforced abolitionist support in the region. The words they spoke at the many meetings they attended are moving and need to be part of another article. It was money from the region, particularly famous radical JOhn Bright, that helped pay in a great part for escaped slave Frederick Douglass' liberty in the USA.

It was no surprise then that Manchester supported the Union and not the Confederacy during the American Civil War. In some ways, despite sending that petition in 1788, this was odd. The American Civil War starved Lancashire and it was the Union's fault. Abraham Lincoln’s side had blockaded the cotton grown in the Confederate states from coming to Britain. Factories, without the raw material, closed, and with them went the work. There was no welfare state so people went hungry. They died. Eventually a relief programme alleviated the situation. Yet for the most part the cotton-producing areas of the county remained solidly behind ‘the war against slavery’. The Mayor Abel Heywood wrote to President Lincoln and Lincoln wrote back, both with grand words.

Years after the war the Anglo-American Committee donated the statue of Abraham Lincoln (orginally to London) we can see in Lincoln Square in Manchester, noting that: ‘“The sentiment of London was quite against the Northern States, but Lincoln found in Manchester warm friends. It is owing not a little to the way in which the English cotton spinners stood by us which enabled us to preserve the Union. For this reason we are very grateful.”

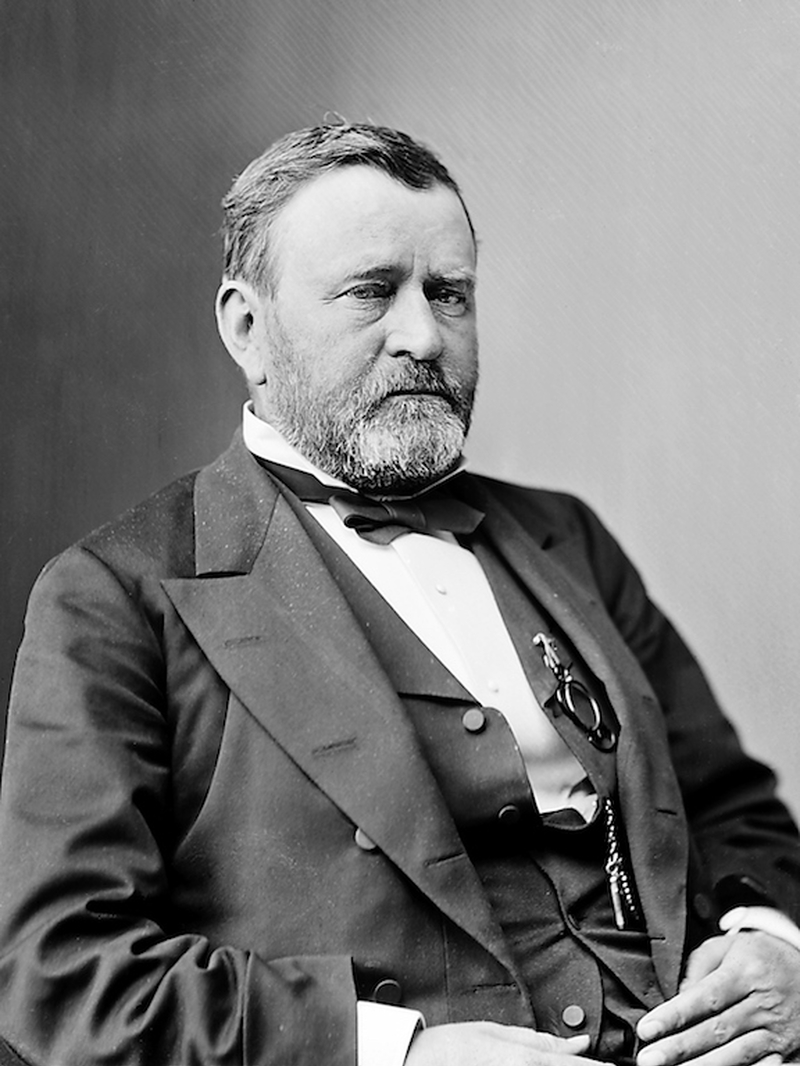

The first guest to stay over in Manchester Town Hall was intimately connected with Lincoln. He was the 18th President of the USA and the man who had commanded Lincoln’s army during the American Civil War. Ulysses S Grant arrived in Manchester in May, 1877, just a few months after leaving the White House. He was on a tour across the globe, looking for private rest and financial reward after his years of public service. On May 30 it was reported 'he remained during the night at the Town Hall as a guest of the Lord Mayor.'

Because of the status of the visitor the council had decided to use the building before the formal opening in September. At his reception Grant said: "I was very well aware during the war...of the sentiments of the great mass of the people of Manchester towards the country to which I have the honour to belong, and of your sentiments with regard to the struggle in which it fell to my lot to take a humble part. For that, and for further expressions of the kind which took place during our great trial, there has been on the part of my countrymen a feeling of friendship towards the people of Manchester, distinct and separate from that which they feel for all the rest of England."

Grant’s host was Abel Heywood who had sent those letters to Lincoln more than a decade before.