Part three of Jonathan Schofield’s history of the city (1600-1660)

Don't forget to read - Part one: the Romans cometh and goeth and Part two: charters, American states and drinking rules

The city has been lucky in hosting not just lots of interesting characters and eccentrics, but also truly significant people. John Dee was Warden of Manchester from 1595 to 1605, from the age of 68 until three years before his death.

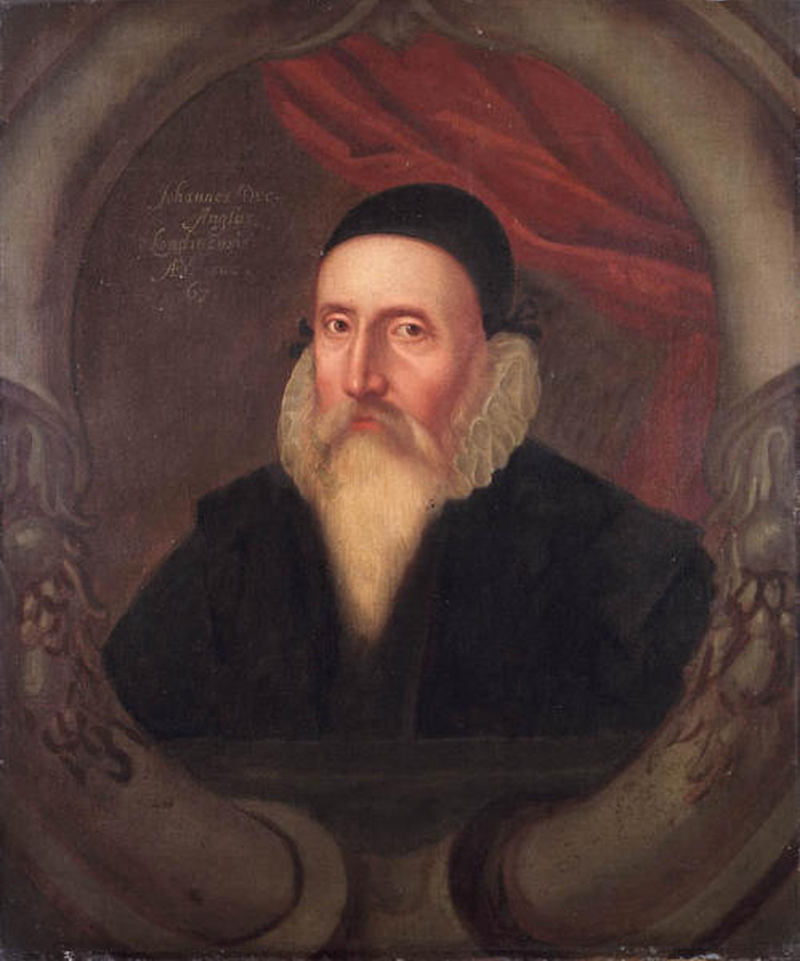

Dee was a polymath and then some. He was an astonishing mathematician and scientist, a leader in his field and internationally famous. But nobody really remembers him for that. They remember him as an alchemist and enchanter, as the inspiration for Shakespeare’s Prospero in The Tempest. He looked the part, certainly as he got older, with his long cloak, white beard and skullcap. The popular image of a wizard may stem from Dee.

Alchemy costs a lot of money however, especially as it’s a complete waste of time. In the end you simply can’t turn base metals into gold. It doesn’t even help much to have the most famous scryer of the day as your assistant. This was Edward Kelly, who convinced most people he met he was the world’s best crystal ball gazer, on chatting terms with angels and demons. Some thought he was a necromancer, a man who raised the dead. One Lancashire story says he was from Chorley, and if you go out in that town on a Saturday night you’ll see it still happens there.

Unfortunately for Dee, Kelly was possibly the greatest occult charlatan that ever lived, and while the pair were trying to achieve alchemy abroad in the Holy Roman Empire and running short of ideas, Kelly told him the spirits were saying that the pair needed to share wives if they wished get anywhere.

They may well have done so for a short time, Dee taken in by Kelly’s twisted reasoning – after all, it was a spirit guide telling Kelly that this was necessary. Dee hated the arrangement, as did his beloved wife, Jane, who’d married Dee at the age of 23, when he was 51. The despised bed-hopping led to a break-up of the Kelly alliance.

Dee turned up in Manchester because he was broke and needed a job. By this time Jane had borne him at least eight children – although one may have been Kelly’s. The Wardenship of Manchester gave Dee an income as the spiritual leader of the town and a role as an administrator and arbitrator. Not that it turned out well. Dee was unpopular in the town through his supernatural investigations and was also cheated out of cash. Worse still, the plague struck and Dee’s beloved wife died along with as many as four of his children.

His official residence and workplace remains with us, Chetham’s medieval buildings, now the Library and the Music School. The library holds a few examples of Dee’s once famously extensive book collection including a tome signed by him in which he’s drawn a little topless woman. This is in a book of remedies by Conrad Gesner from 1555, and in this case gives advice on how to maintain pertness in a woman's breasts as she gets older (cinnamon paste apparently). Clearly Dee couldn't help joining in with an artistic rendering of his own.

In March 1996, on the anniversary of Dee’s death, a local paranormal group, Manchester Area Psychogeographic, attempted to levitate the Corn Exchange. The group believed Dee had lived for several years on the site while in Manchester. A member of staff in Harry Hall’s Cycles, then in the Corn Exchange, said a bike might have fallen off the wall. Architectural levitation, like alchemy, remains elusive.

Thirty seven years after Dee's death, in 1642, Manchester was one of very few towns in Lancashire to support Parliament against King Charles I. The dispute, that led to 200,000 deaths in England and Wales, and more again in Scotland and Ireland, was principally over whether the King ruled through Parliament or by divine right. In other words, was Charles I’s power absolute? Parliament said no, the King said bugger off.

Mercantile towns and cities generally sided with Parliament, after all they were big tax payers and wanted a degree of control over the revenues they raised.

Manchester bears the dubious distinction of claiming the first casualty of the war. In a skirmish on Market Street during the hothead months leading to open war, Richard Perceval, linen weaver, was shot dead. The town was also, perhaps, the second town or city to be besieged after Hull.

On 25 September 1642, Lord Strange, in command of several thousand Royalists, attacked the town along Deansgate and across Salford Bridge. Strange was the first son of the Earls of Derby, now the proud owners of exotic global beasties at Knowsley Safari Park. Traditionally, first sons of the Derbys were entitled Lord Strange. Strange became the full Earl during the siege when he received news of his father’s death.

When Strange demanded the town give up its store of gunpowder and its weapons, he received the reply that he would get ‘nothing, not even a rusty dagger’. The defenders were led by Robert Bradshaw and William Radcliffe under advice from Colonel Rosworm, a German mercenary, who’d been hired by the Parliamentarians for £30. The Royalists then offered him £150, but he refused as ‘honesty is worth more than gold’.

It rained every day during the seven days of the Royalist presence. As assault after assault broke on the barricades Rosworm had erected across streets in an unwalled town, the make-shift soldiers gathered by Strange began to lose heart. On 29 September, the popular Captain Standish was killed by a lucky sniper’s shot from the church (now Cathedral) tower. Another desperate attack came on 30 September. At the battle's height two barns caught fire, the smoke from which caused confusion. It was raining more heavily than ever. As the smoke cleared it became clear the assault had failed. Strange lifted the siege, still in the rain, on 1 October. ‘You came with fire, but God gave us water’, the Parliamentarians wrote.

The Royalists apparently lost 200 men, the defenders a mere four, plus ‘a strange boy’ who was ‘gazing about him’. These figures may carry poetic licence as they were declared by the victors. It seems likely there were far more Parliamentary deaths. It would have been nice to find out a little more about the ‘strange boy’ as well. Why was he ‘strange’, why was he ‘gazing about him’ during a battle?

What is clear is that the Royalist commander was a useless soldier. He ignored basic principles of warfare by attacking uphill over the bridge between Manchester and Salford, or along level ground on Deansgate, when he could have attacked down the steep lanes (much steeper than at present) of Market Street and Shudehill. He went on to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that he was useless in just about every one of his subsequent actions. He was brave but daft, the cliche of the cavalier. As the Earl of Derby he would lose his head, executed for his command of Royalist forces in the massacre at Bolton in 1644.

After the victory Manchester became the headquarters of Parliament in the North West, and following the triumph of Parliament and Charles I’s execution, eventually gained its first Member of Parliament as a reward. The new MP was one of the local gentry: Sir Charles Worsley from Platt Hall in Fallowfield.

The situation changed rapidly under the austere republican dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell. The town, like so many places in the country, was more than ready for the return of a monarch, in this case Charles II. His coronation in 1661 was extravagantly celebrated and the conduit, the main water supply to the town, was said to run with claret. Not that the Royalists had forgotten Manchester’s support for Parliament, and the town’s right to have an MP was removed in a act of petty vengeance. Manchester wouldn’t have a representative in Parliament again until 1832.

Just for the record, it stopped raining on 2 October 1642, the day after Strange had lifted the siege.