THE first guest might as well be a notable one.

There has been on the part of my countrymen a feeling of friendship towards Manchester, distinct and seperate from that which they feel for all the rest of England

While researching the second Lost & Imagined Manchester book I came across something I wasn't looking for. This is the serendipity of research and also its risk. The job you intended to do is forgotten as you pursue an intriguing but diverting lead.

Thus while researching the area of the city demolished to create the Arndale I came across a reference to a distinguished guest staying in the Town Hall. But I assumed it was the old Town Hall not the one we have presently.

The guest was the 18th President of the USA and the man who won the American Civil War for Abraham Lincoln: Ulysses S Grant.

Grant arrived in Manchester on Wednesday 30 May, 1877, just a few months after leaving the White House. He was on a tour across the globe, a private rest and reward after his years of public service.

There were the usual rounds of speeches and visits to classic Manchester institutions such as the Royal Exchange. There were also endless toasts which Grant probably didn't mind as he famously loved a drink. On May 30 it was reported 'he remained during the night at the Town Hall as a guest of the Lord Mayor.'

The present Town Hall didn't open until September of 1877. It included a residence for the Lord Mayor. In a mealy-mouthed, penny pinching, moment in the 1980s the five bedrooms and spacious bathrooms were converted to offices. It was tantamount to civic vandalism.

The Lord Mayor's apartments occupy this corner of the Town Hall

The Lord Mayor's apartments occupy this corner of the Town HallThe Lord Mayor's offices still exist of course, grandly occupying the north west corner of the building, but the residential element has been ditched. Shame that. Still, given the disparity between the date of the opening and the date of Grant's visit I thought he must have stayed the night at the old Town Hall. But something was bothering me, after all nobody had recorded any living accommodation in the old Town Hall, so I looked up the Manchester Guardian archive for May 31 and June 1, 1877.

The paper confirmed the rediscovery of a happy historical fact. It reads: 'Grant is the first visitor who has been received at the new Town Hall, and Manchester is now, for the first time, able to welcome and provide accommodation for its guests in a manner befitting the position which it holds among the cities of the world.'

Because of the status of the visitor the council had decided to use the building before the formal opening. So not only was Ulysses S Grant the first visitor to the building, his formal reception and the speeches surrounding his visit were the first in the present Town Hall as well.

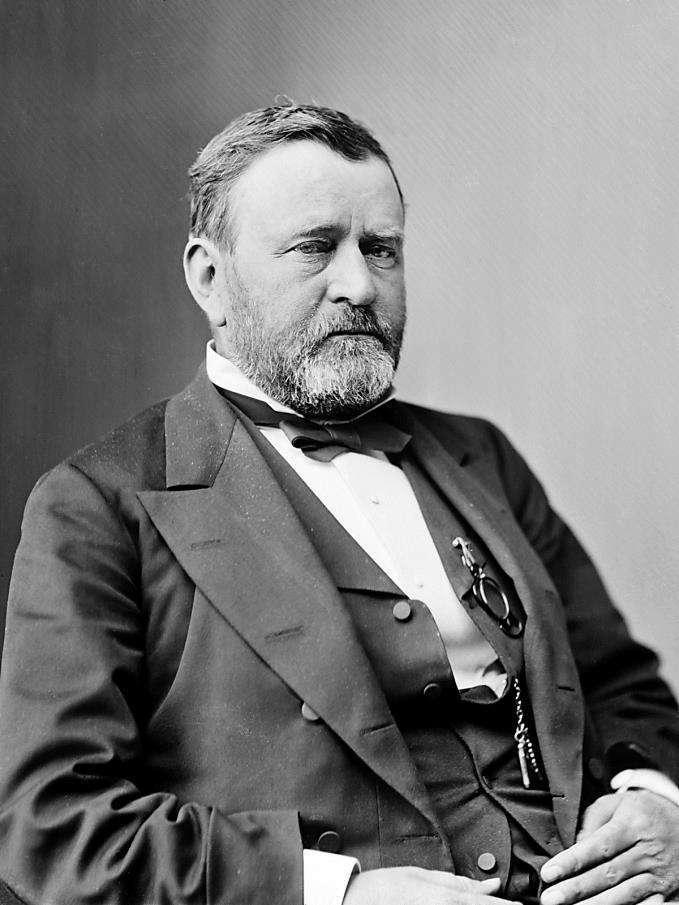

Grant around the time of his visit

Grant around the time of his visit This was an auspicious start for the building. Grant is an extraordinarily significant figure.

It could be said he was one of those men of destiny who only come into their own at times of crisis - Churchill was similar. A successful soldier as a young man he'd had to resign his commission through drink. "The vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision," he recalled. In reality he was forced to leave because of his drinking.

After that spell in the army Ulysses became useless. He failed at the jobs he attempted. This was bad timing, he and his wife Julia were trying to bring up young children. During the worst of the lean years he was reduced to selling firewood on a street corner to make ends meet. Whilst attempting to be a farmer he acquired a slave, William Jones, from his father-in-law but freed him two years later when he could have potentially made over a $1,500 from a sale and thus given his family respite. Grant, though, was now convinced of the vileness of the slavery.

It's also pretty clear that Grant was a man of his times with faults we would now find unconscionable but still he had the imagination in much of his life to escape those times - as with Churchill, again. Can we say the same about ourselves?

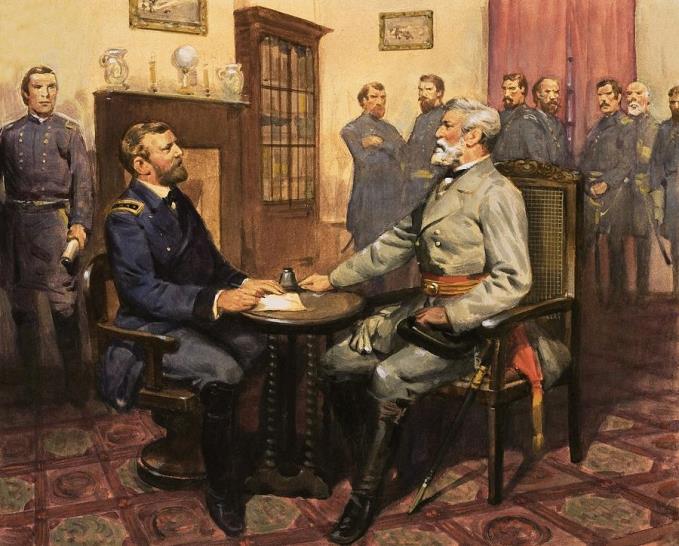

Civil War came in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers and Grant soon found himself back in a world he was innately suited for: that of soldiering. With a new commission and a reputation as an aggressive commander he rose through the Union ranks until on 3 March 1864 he was given command of all the Union armies. He was just 41-years-old. A little over a year later Grant took the surrender of the main Confederate general, Robert E Lee, at Appomattox Court House and the American Civil War was effectively over. Many saw Grant's generalship as the prinicipal component of the Union victory.

Grant on the left, Lee on the right at Appomattox

Grant on the left, Lee on the right at AppomattoxGrant became president for the first of two consecutive terms in 1868, beating the discredited incumbent Andrew Johnson. Grant wanted the 'reconstruction' of the Southern States to accelerate full equality for black Americans. He passed measures to ensure the implementation of equality by military force if necessary and he directly attacked the Klu Klux Klan, breaking the immense influence they had in the South. Sadly, later administrations allowed inequality to come crashing back, an inequality which went largely unchallenged until the Civil Rights movements almost a century later. Grant also wanted to ensure dignity and peace for the Native Americans. He failed but he tried - an Obama moment given his failure with health policy and guns. In his second term his reputation was tarnished by failing to deal with a depressed economy and through a botched foreign policy.

His presidential reputation was also dogged by allegations of favouritism and corruption in key agencies, yet he was immensely popular amongst Americans and others. On his world tour he was received with enthusiasm everywhere he went. His mausoleum in New York is the largest in the US dedicated to a single individual.

A curious and charming image of the vast Grant Mausoleum

A curious and charming image of the vast Grant Mausoleum General Grant National Memorial, Riverside Park, New York

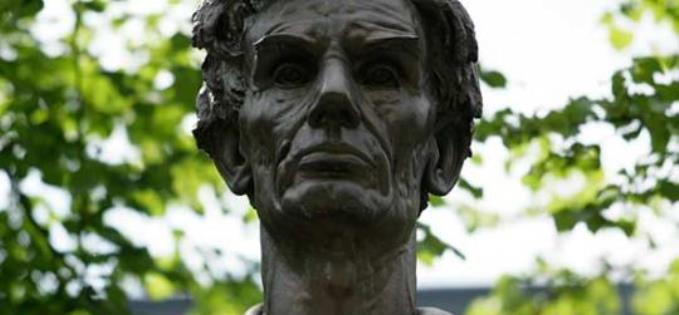

General Grant National Memorial, Riverside Park, New YorkA short walk from Manchester Town Hall is Lincoln Square with the statue of Abraham Lincoln. Grant was supposed to be at Ford's Theatre with Lincoln but turned the invitation down as he was travelling away from Washington with his wife the following day. Good decision. It's believed John Wilkes Booth, the assassin, had targeted Grant as well as Lincoln. At Lincoln's funeral Grant stood alone and wept for what he considered "the greatest man you could ever know".

Manchester tells stories about its close relationship with the Union side in the American Civil War and its support for anti-slavery which resulted in the gift of the statue. Clearly that was the case, but it's always good to have those stories reinforced from the horse's mouth - or at least the 55-year-old general's mouth.

Lincoln in his eponymous square

Lincoln in his eponymous squareAt the Town Hall reception in May 1877 Grant said: "I was very well aware during the war...of the sentiments of the great mass of the people of Manchester towards the country to which I have the honour to belong, and of your sentiments with regard to the struggle in which it fell to my lot to take a humble part. For that, and for further expressions of the kind which took place during our great trial, there has been on the part of my countrymen a feeling of friendship towards the people of Manchester, distinct and separate from that which they feel for all the rest of England."

The Lord Mayor of Manchester at the time was Abel Heywood, himself a remarkable man, who not only has the main hour bell of Manchester Town Hall named after him - Great Abel - but also a pub in the Northern Quarter. We described a little of his life in our review of the latter pub here.

Great Abel waiting to ring the hours

Great Abel waiting to ring the hoursIn my mind's eye I've created a scene in my head.

In the dramatic High Victorian and lush surroundings of the Lord Mayor's apartments Abel Heywood and Ulysses S Grant are having a nightcap, discussing the experiences that formed them. Their ladies have retreated to their respective bedrooms. It's the early hours and the two men give one final swirl of a single malt before toasting each other and retiring.

"We couldn't have had a better start for the new Town Hall. Goodnight Ulysses," says Heywood.

"Goodnight Abel, that was one great evening," says Grant. Then: "Oh, Abel, one more thing."

"Yeah, Ulysses."

The 18th President of the USA and the Civil War victor looks round the extravagant room in the extravagant Town Hall and cocks a finger at Abel Heywood.

"Nice crib," he says.

Grant during the American Civil War

Grant during the American Civil War