Jonathan Schofield on how Manchester became 'Cottonopolis' and how the ghost of the dead trade still haunts us

Don't forget to read part one (79AD-1066), part two (1066-1600), part three (1600-1660), part four (1660-1746) and part five.

For a couple of centuries Manchester became 'Cottonopolis' - the centre of the global finished cotton trade. Here we break down into bite-sized chunks how the city achieved that and how, in some ways, the defunct trade still defines the physical nature of much of the city centre. (This article should be read in conjunction with the previous chapter of Manchester history.)

How did the city become Cottonopolis?

A repeated part truth is that it has a wet, humid climate ideal for spinning yarn. More importantly south-east Lancashire has steep streams which could provide power for the mills and give soft water for the washing and bleaching of cotton, there is a coalfield to fire steam engines, salt supplies for developing chemicals and easy access to the west coast for importing the raw material and exporting the finished product. Crucially Lancashire’s industrial organisation was fluid. Manchester was unhampered by guilds and trade restrictions. Entrepreneurs were encouraged.

In the beginning

Traditionally textile manufacture began in 1363 with the arrival of Flemish weavers. By the reign of Elizabeth I wool and linen production was important, followed by manufacture of fustians, a mix of linen and cotton. But it was with the manufacture of pure cottons in the mid 18th century that Manchester became significant. The process of production was run on the ‘domestic system’. Merchants ‘putting out’ raw cotton to spinners, weavers, cutters, bleachers, etc… who worked from home.

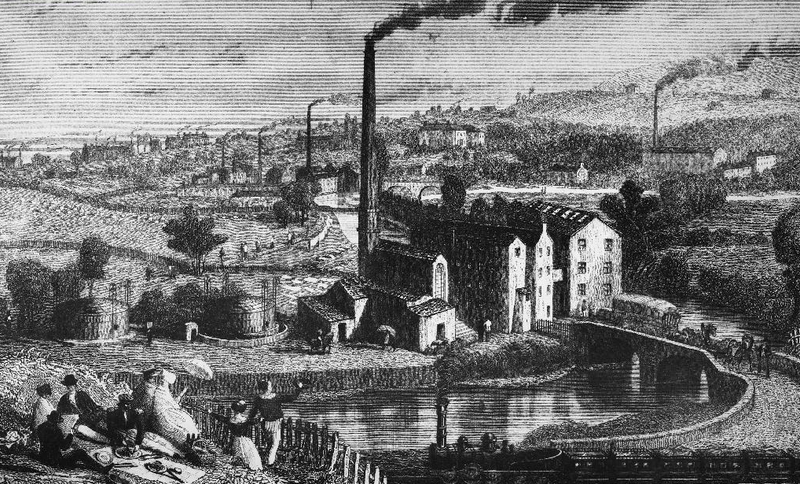

Technological advance gradually swept this method away and the factory system took over. Kay invented the Fly Shuttle in 1733, between 1760 and 1790, Hargreaves invented the Spinning Jenny, Arkwright, the Water Frame and Crompton, the Spinning Mule. Meanwhile good turnpike roads were improving communications, cheap coal arrived with the Bridgewater Canal in 1761 and the first steam mill fired up in 1783. Cotton was being imported at a rate of 1000 tonnes a year by 1751, and stood at 45.2 thousand tonnes by 1816.

In its heyday

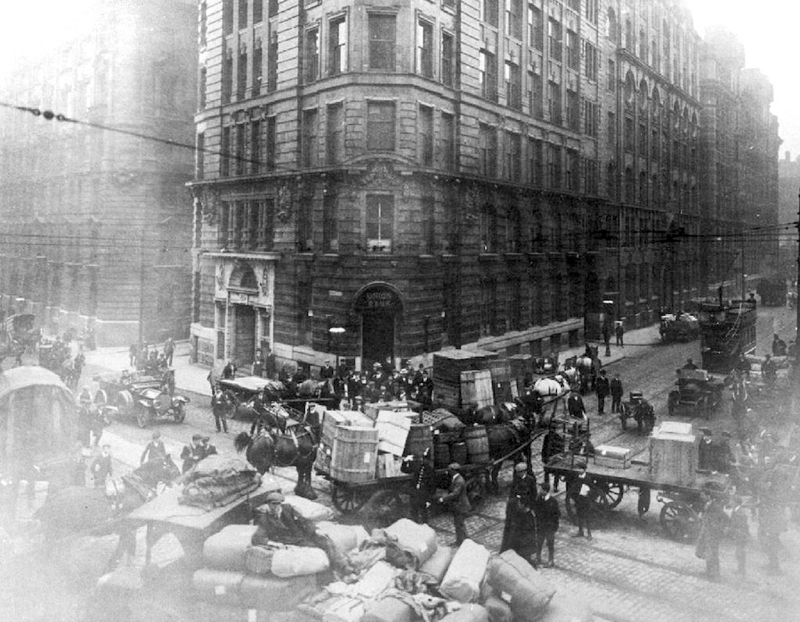

By 1841 imports of raw cotton had risen to 205 thousand tonnes and they would peak in 1914 at almost a billion tonnes. The character of Manchester changed. The cotton mills employed less in the city as the century wore on, by 1840 only 18% of the work force worked in cotton manufacture. Manchester became the commercial centre of the industry, its clearing house. The dominant building was the stately warehouse for the display of finished cotton goods or the ornate bank and office providing loans and credit for the production of cotton.

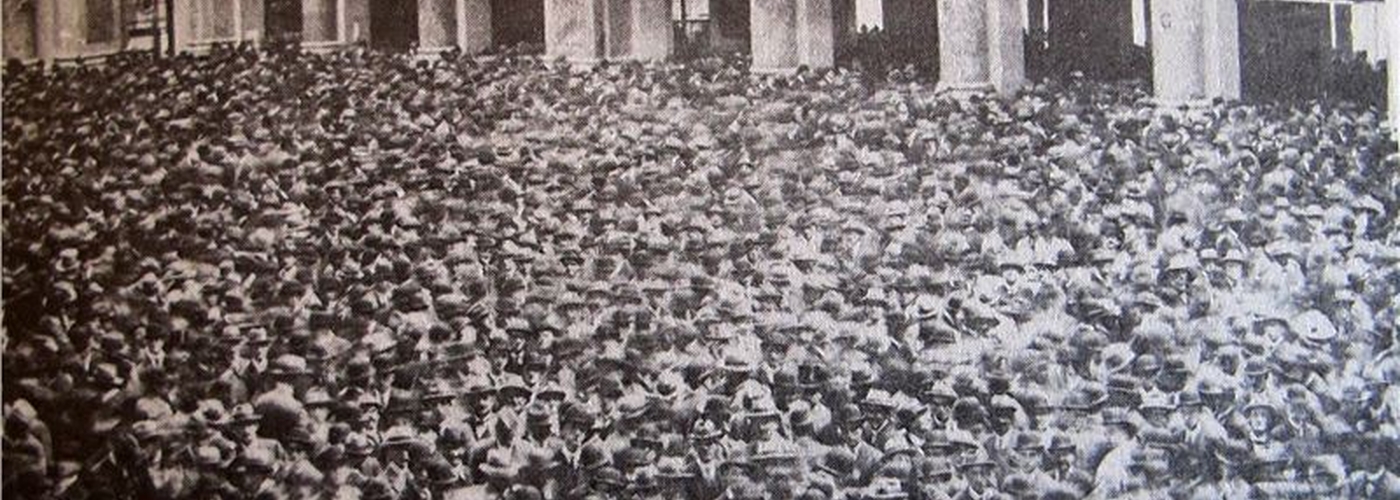

Above all Manchester was the town of the Royal Exchange, where thousands of traders would meet on Tuesdays and Fridays to do business. Production became concentrated in the outer towns, spinning nearby in Bolton, Oldham and Stockport, weaving in towns to the north such as Preston, Burnley, and Blackburn. The trade in cotton amounted to 50% of British exports in the 1830s, and stood at 80% of global cotton piece goods in the 1880s.

The decline of the industry

Reliance on a distant raw material made the trade vulnerable. The American Civil War showed this, when the supply from the Confederate States had been blockaded by the Union North. Sourcing raw cotton from India and Egypt and the growth of trade with the British Empire maintained the industry until after WWI. But business declined as production rose in countries close to the raw material and with cheaper labour or with more up-to-date methods. To shore up the industry, there was a rise in tariffs for cotton imports plus schemes to reduce excess production. It was too late, a reluctance to develop new business practices and to invest in new machines, e.g. move from spinning mules to ring spinners, cost the trade dear.

What remains?

A great arc of the city centre from the south through the east and into the Northern Quarter and Ancoats is still defined by Cottonopolis. These are the main building types to spot.

Weaver’s cottage

A surviving ‘domestic system’ buildings dating from the late 18th century are dotted across the city. The Grey Horse pub on Portland Street has distinctive second floor windows maximising light for the intricate labour of weaving or spinning, as does the Vine pub on Kennedy Street. This system of working from home gave way to the dehumanised but efficient factory system in the early 19th century. For handloom weavers this was a decline from self-employment into wretchedness – small wonder that they played a part at the Peterloo Massacre (which will be described in the next in the series).

In many similar properties owners profiteered on overcrowding by dividing the house between various families. Cellar dwellings – note the windows below street level – became notorious with families living on straw and sacking in damp conditions without basic sanitation.

Manchester Palazzos

By the 1840s the Renaissance Palace and been adopted as a model for warehouses. The simple but stately design allowed plenty of light whilst not wasting too much space on decoration. The main salesrooms with cotton samples were on the upper floors, the first floor provided the counting house and the administration whilst the lower basement contained the machinery, the steam engines and the boilers. A large iron gateway led from the rear or side through which cotton carts left. The heavy carts cracked stone kerbs so iron kerbs are a feature in the surrounding streets.

As C.R. Reilly (1924) described: ‘[the] warehouses represent the essentials of Manchester’s trade, the very reason for her existence. They are too near to her heart, for any light treatment. Hence their simplicity, strength, and sincerity, and consequently their real beauty.’

Packing Warehouses

The huge packing warehouse was a late 19th century and early 20th century development. Instead of sole occupancy these were split between several companies. Here ‘finished cloth went to a packing warehouse for quality control, making into a piece, labelling and baling for shipment and storage before it was ready for export.’ (Nick Dixon 1997).

Typically terracotta or Portland stone, packing warehouses are monumental structures. St James House, on Oxford Road, has a Baroque façade of Portland Stone. It was built in 1912 for the Calico Printers’ Association and contained over a 1000 rooms. Round the back there is a functional grid of concrete and glass. Oxford Road, Great Bridgewater Street and Whitworth Street are filled with these edifices.

The Mills

Between Jersey Street and Redhill Street, half a mile from Piccadilly Gardens alongside the Rochdale Canal you’ll find ‘dark satanic mills’ now converted to commercial or residential premises. There was a campaign to get these and other the central warehouses registered as a World Heritage Site with UNESCO. It didn’t happen as the council thought it would make future development more difficult. The oldest is Murray’s Mill of 1798, and the last is from 1912.

French writer Alexis de Toqueville commented in the 1830s about the largest here, McConnel and Kennedy: ‘1,500 workers labouring 69 hours a week…three quarters of the workers in (the) factory are women and children.’ To visitors the scale of the new industrial process was something far beyond their range of experience. ‘Here are buildings seven to eight storeys, as high and as big as the Royal Palace in Berlin,’ said the German architect Schinkel in 1825.