Andrea Sandor recaps Jacqui Smith’s talk at the People’s History Museum - from ‘brave’ May to the ‘flippin’ nightmare’ of Labour in Scotland

Over a year and a half ago, Jacqui Smith warned us not to write Theresa May off yet. It seems the former Labour Home Secretary knew a thing or two, foreshadowing not only May’s rise as Prime Minister post-Brexit but also her move to call a snap election in June.

That astute foresight is enough to convince me to head over to the People’s History Museum one Friday after work to find out what more Smith has to say. Her talk is part of a series of conversations exploring the significance of Labour’s 1997 general election victory. That year saw the rise of ‘New Labour’ as Tony Blair rebranded the party, gained the centre ground and brought the party back into power after an eighteen-year hiatus.

Theresa May has outperformed expectations and has some of the ingredients necessary to move the Tory party on from the dilettante gentleman, amateur approach of David Cameron

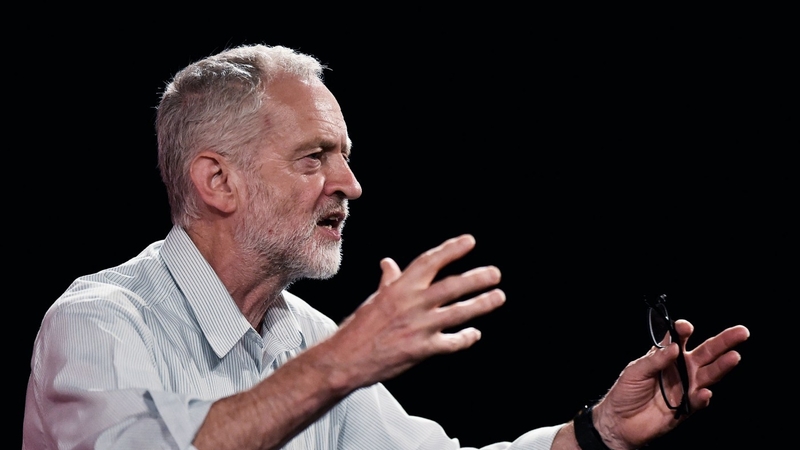

Being at the helm during the Iraq war and 2007 financial collapse, however, left New Labour with little to recommend itself to the electorate and, in 2010, the Tories moved back into Downing Street. But, rather than regrouping in the next decade, Labour continued to dissemble. In 2015, the party veered violently to the left with the rise of Jeremy Corbyn as party leader, propelled by very vocal but minor segments of the population. While his adherents call Corbyn’s left-wing agenda principled, it appears unlikely to resonate with mostof the electorate. As such, the opposition party is posing no opposition at all.

Smith’s words from 2015 are as timely as ever: “Theresa May has outperformed expectations and has some of the ingredients necessary to move the Tory party on from the dilettante gentleman, amateur approach of David Cameron. It is a record and an approach which just might attract both the party and those voters who Labour so desperately needs to win back.”

Today, Theresa May is betting her Brexit-found leadership that Smith is right. With a seventeen-point lead over Labour in the polls, May called a snap election, confident she could win over the centre ground Labour never recovered after losing office in 2010.

“It’s an extremely brave thing to do. You could remove yourself and your party from office. You have to be certain you will win,” Smith tells the small group assembled at the People’s History Museum.

Smith’s respect for Theresa May is palpable, but she says she’s ‘not ready to despair’ about the June election. When asked by an audience member what needs to be done to win in June, she says Labour needs a strong manifesto.

She is open and frank about her views on Jeremy Corbyn, the current Labour leader, admitting that she didn’t vote for him and fearing another defeat like that of 1987, also under a ‘charismatic leader’.

A young woman, presumably a Corbyn supporter, asks whether Labour would be in a better position were different individuals behind the leader. But Smiths says Corbyn isn’t strong at building a team and that she’s not convinced he could be a strong leader.

This frankness will strike some Labour supporters as being disloyal to the party. But Smith believes that Jeremy Corbyn is damaging the party she loves, and speaking out against him is, to her mind, the most honest and loyal thing she can do. The divisions within Labour are deep, and it’s difficult to imagine how they could possibly be mended in time to win the June election.

Labour’s dire position is perhaps most clearly defined in Scotland. “It’s a flippin’ nightmare. We won ‘Better Together’ and lost Labour,” she laments, referring to the Scottish National Party displacing Labour after the independence referendum. Labour’s one remaining MP seat in Scotland may well diminish to none as the Tories, historically loathed in Scotland, are set to increase their share.

So does Smith provide any clues as to what went wrong with Labour? Over the course of the evening, she identifies three main contributing factors.

“Globalisation in the UK wasn’t working,” Smith says. Rather than reeling in some of the financial deregulation Thatcher had unleashed, New Labour embraced the free markets. ‘”We didn’t properly recognise that type of insecurity,” she admits, referring to the existential insecurity that emerges with the disappearance of local industries and influx of cheap labour.

The party ‘wasn’t talking to its heartland’, Smith concedes. While she argues that Tony Blaire did successfully engage the working class and that Labour funneled money to the poorest areas in the country, she recognises that the heartland was taken for granted with no activists working there. She also thinks that the party was too cautious of local government.

Smith argues that Labour didn’t defend its record hard enough after losing power in 2010. Looking back, the party achieved a lot; including improvements in education, health and inequality. A small taste includes decreased poverty rates among children and pensioners, shorter NHS wait times, 42k more teachers, smaller class sizes, and the introduction of the national minimum wage, the Human Rights Act and the Climate Change Act. Hey, you can even go to the national museums and galleries free of charge thanks to New Labour.

While these advances under New Labour haven’t become associated with the party, a false legacy has. “Why,” one man asks, nearly in tears, “do people think Labour caused the collapse?”

Smith shakes her head, her expression a mixture of sadness and incredulity. While the 2007 financial collapse started in the United States and spread across the world, Smith argues that Gordon Brown led the international community in containing the crisis. But Labour, once again she argues, didn’t communicate that loudly enough.

So we return to our first question: what needs to be done to win the June election? Smith says Labour needs a manifesto. Well, that manifesto had better be gold.