Jonathan Schofield makes a fascinating discovery in a Chorlton churchyard

Digging in a graveyard is risky enough during the night, let alone during the day. This is especially the case if you’re not an official gravedigger.

There was an old man with a small dog observing me. “It’s good somebody is paying attention to the dead,” he said

People stare if you are, say, worrying the soil in St Clement’s old churchyard in Chorlton-cum-Hardy on a Tuesday at around 2pm with a shovel and a litre of water. They sit on the picnic tables outside The Bowling Green pub pointing and muttering.

Yet us British are a curious breed and, though unofficial digging in cemeteries is worthy of comment or even interruption, only three people asked me what I was up to. I even ran out of the water I needed for my task and went into the Bowling Green for more water and told them what I was doing.

“Oh, ok then,” was the reply from the barman, as though this was typical Tuesday afternoon behaviour in Chorlton.

Anyway, back in the graveyard my endeavours met with success. I had uncovered the tombstone of a Manchester hero of the late eighteenth century. I found the memorial stone to Thomas Walker: radical, philanthropist and a principal leader in the movement to abolish slavery.

Earlier that day I had been going over my notes for a Zoom tour involving the abolition of slavery. Somewhere amongst all the scribbling I’d written some sentences which hadn’t nobbled my attention previously. This was that Walker had lived at Barlow Hall, then Longford Park, and he was ‘buried in Chorlton.’

He died in 1817 so that meant he had been buried either in Rusholme Road Cemetery, Chorlton-on-Medlock, or in the old St Clement’s graveyard in Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Yet Walker was an Anglican and Rusholme Road Cemetery was for dissenters - non-conformists, Methodists, Quakers and the like. So probably 'Chorlton' meant the south western Manchester suburb.

I cycled to Barlow Hall, now the clubhouse of Chorlton-cum-Hardy golf club, and took a picture for the tour. The oldest part of this attractive house dates from the 1570s. On the way I’d taken a picture of the surviving porch of Longford Hall which had been the home of John Rylands and his wife Enriqueta who dedicated the famous library on Deansgate to her husband when he’d popped his clogs. The house dates from the 1850s, so after Thomas Walker, but the park was his for a while.

Then I went to St Clement’s old churchyard on a wing and a prayer. The last burial had taken place in 1916 and in the 1930s the bodies had been exhumed and reburied in Southern Cemetery but the gravestones extending from wall to wall had been retained. There had been 380 burials in total. Then in the eighties the churchyard was landscaped and lost perhaps seven eighths of the stones. Some of the ledger stones (the long memorials laid flat over the grave) were kept and positioned arbitrarily to create a path from Chorlton Green to the Bowling Green pub.

I read every stone all the way to the Bowling Green. I read the last two memorials stood on a stone that was largely obscured by soil. I thought 'oh well, his stone is not here, nobody in the eighties had probably given a thought to this great man and his stone had disappeared.' Then I looked straight down and saw ‘lker’ peeping from under my shoe. I lifted my foot and the word Walker popped out. Hannah Walker. Hannah had been Thomas’s wife’s name. Further up the stone I thought I could make out Longford. Much of the stone was covered by soil and impossible to read.

So I returned home and fetched a shovel and bottle of water and started scraping at the dirt and then washing it away. One woman walking past asked me what did I think I was doing. “Resurrecting a great Mancunian,” I said and explained. She said: “There should be a blue plaque up to him if all that’s true.” She had a point.

I paused at my scraping away of the stone with that feeling someone was watching me. It was an elderly gent with a small dog. “It’s good somebody is paying attention to the dead,” he said and continued on his way. A worker in a hi-vis jacket asked me in an injured tone what the hell did I think I was doing. I explained and he said, “oh, nice,” and left.

I was rewarded for my efforts. At the top of the stone I was working on appeared the words ‘Thomas Walker of Longford.' The date of death was 2nd February 1817. Spot on. I’d found my fella’s tombstone. There was no indication of his contribution to Manchester life. It was a humble stone but then Walker’s radicalism had cost him his textile businesses and his money.

I celebrated with a pint in the Bowling Green and raised my glass to a man who had successfully fought off a charge of high treason in the name of liberty and who fought so hard to achieve the abolition of the slave trade. A real hero of this city. Forgotten and now found.

Who was Thomas Walker and why is he a Manchester hero?

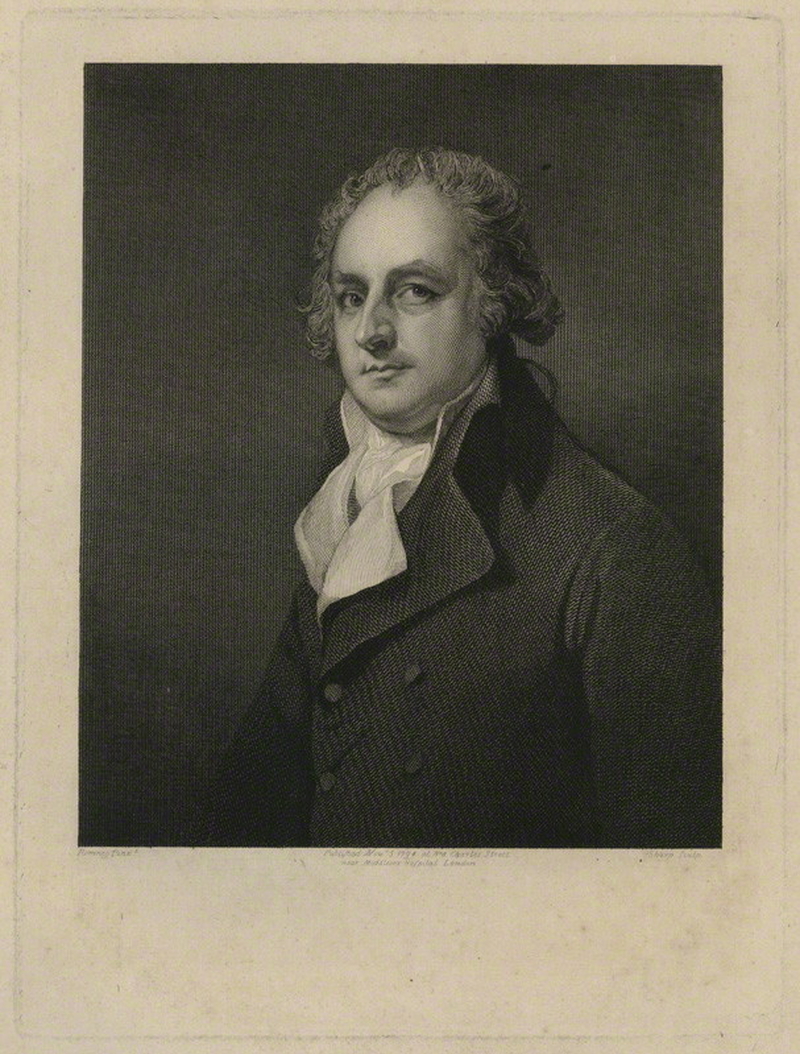

Born in Manchester Thomas Walker was a successful cotton merchant. He was radical in his politics and an ardent supporter of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, where he met other reformers such as Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce.

It was he along with another kind and generous Mancunian, Thomas Butterworth Bayley, who invited Clarkson to speak at Manchester Cathedral in October 1787 which led to Manchester sending the first petition to Parliament from a town or city demanding the end of the UK slave trade.

Walker then became the organiser of the Manchester anti-slavery group. He chaired the first Manchester committee of 31 people in December 1787. His wife, Hannah, also named on the gravestone, was listed as one of the female subscribers to the committee. Walker helped organise the 1788 petition to parliament for the abolition of the slave trade, which contained 10,639 signatures, which was perhaps as much as 20% of the population of Manchester and Salford.

The full story is told here.

Walker also founded a local branch of the Society for Constitutional Information which included Josiah Wedgwood amongst its members. The society was 'dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine who had written Rights of Man and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.'

Walker was a founding member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1781 which was dedicated to promoting learning but also practical matters such as improvements in local health and sanitary issues.

In 1792 he set up the radical newspaper the Manchester Herald to counteract the influence of the Tory Manchester Mercury. His activities as a radical put him at odds with the establishment supporting 'Church and King' party in Manchester. In December 1792 his warehouse and business premises were attacked on three and four occasions. Even his city centre house was attacked and he and his supporters had to use gunfire aimed over the heads of the mob to drive them away.

In 1794 he was charged with treason which could have cost him his life. He eventually went to trial on a charge of sedition but the main witness a man called Dunn was drunk and contradicted his previous evidence so Walker was acquitted. His defence cost him £3000 and ruined him.

Walker eventually retired from public affairs and lived out his life at Longford.

By the way, the gravestone reveals a curiosity of the age. It states Walker was born '3rd April 1751 (New Style).' His biographies state he was born on 3rd April 1749. The 'new style' on the tomb refers to the change of the calendar in 1752 from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar which messed with the dates. This must explain the discrepancy between the tomb and the official biographies.

You can join a Jonathan Schofield tour or buy a Zoom tour here.