Ellie-Jo delves into the basement of the RNCM to discover its wonders including a trumpet made from a human thigh

12 minute read

When I think of archives, I think of dusty documents tucked away in glass cabinets or a jumble of objects in a locked room that looks a bit like the flat in Steptoe and Son. Then I went to the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM) and had a chat with their College Archivist, Heather Roberts.

Manchester should have a music museum, and not just one adorned with black and yellow stripes and a massive mural of Ian Brown

I’ve been to the RNCM loads of times to perform with my dance school, but I had no idea about the objects in the basement. A rich and fascinating tapestry of musical history is sitting right there on Oxford Road, and it deserves a shout-out.

Recent initiatives like The British Culture Archive and the British Pop Archive have proved extremely popular with their collections of old photographs and memorabilia like Johnny Marr's Gretsch Super Axe guitar and Ian Curtis’ handwritten lyrics. They attract visitors to museums, galleries and libraries every year because people love Manchester’s musical history - so why isn’t the RNCM’s collection on public display?

A gradual curation over time

The archive was established around 20 years ago as an actual collection of service, but prior to that there were two music colleges in Manchester, The Royal Manchester College of Music founded in 1893 by Sir Charles Hallé, and The Northern School of Music founded in 1920 by Hilda Collins. These two schools came together in 1972 to form the RNCM and the archive came as a transferred asset.

Heather explained that “the collection was kept in the library as a special collection, but there was no functioning archive service. With the original collection came a couple of individual assets like the Alan Rawsthorne collection and the Thomas Pitfield collection, but the actual library building wasn’t finished until the the late nineties.”

After it’s completion, the RNCM began to play host to collections like the historical musical instruments collection, and because of this, the college is able to actively collect other materials as a full heritage service.

You can almost smell the genius

The RNCM archives are fascinating, and everything is all kept in one place, so it feels like it’s own curated exhibition. Heather adds that the archive is especially important as “it has all of these incredible stories to tell, and to have this kind of acknowledgement and appreciation for heritage and history from a non-heritage organisation is a dream as an archivist. It’s very cool”

With everything from handwritten letters to musical scores, bizarre instruments, and a fragment of Beethoven’s shroud, my tour around the library was a bit of a ‘pinch me’ moment. Heather also had “a moment” when she was introduced to the Brodsky collection in particular.

Adolph Brodsky was a Russian touring violinist who came to Manchester to teach. The violinist was friends with Tchaikovsky, Edward Elgar, Nina and Edvard Grieg and Johannes Brahms to name but a few, and this internationally renowned set of composers all sent letters back and forth to one another. These handwritten letters sit in the archives at the RNCM.

Heather explains that, “this incredible pocket of late 19th and early 20th century composers massively contributed to the boom in concerts and timeless classical compositions, and their handwritten thoughts are right here in this building.” I was lucky enough to hold one of Tchaikovsky’s letters with my own bare hands, and as Heather jokes, “you can almost smell the genius.”

Hands, thighs, and a piano as old as Francis Drake

A lot of the instruments in the eclectic RNCM collection can be viewed online, but seeing them in the flesh is crazy.

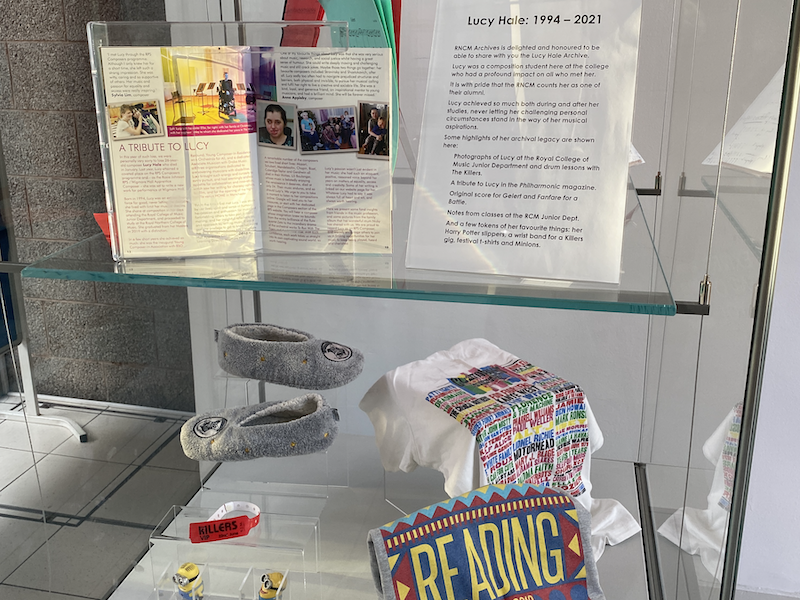

Another highlight is the more recent collection belonging to Lucy Hale, a 26-year-old composer who studied at the RNCM and helped young disabled musicians to write and perform before her untimely death in 2021. “As a female composer, Lucy was a really interesting person, and as someone who’s movement was severely restricted by a neuromuscular disease, her achievements are incredible.”

Heather goes on to add that “The RNCM is not just an archive for music, it’s an archive for people, and that’s what history is, it’s not times and dates and places and outputs, its people. The human aspect of the collection ranges from Tchaikovsky to Lucy Hale which is really special”.

In terms of instruments, things don’t get more unusual than a trumpet made from a human thigh bone, but that barely scratches the surface. There’s a French Flutina from 1860, some Scottish pastoral pipes from 1760, and an Italian polygonal virginal from 1540 that’s as old as Francis Drake. If you’re into sitars, this is your gig.

My favourite curiosity is the buccin bass trombone from Lyon that’s shaped like some kind of fairytale serpent/crocodile, and that’s a sentence I never thought I’d say.

Looking after it all

The archive is very much a multimedia collection, which Heather adds “is both a blessing and a curse”. As well as all of the instruments, letters and scores which have to be stored at the correct temperature, humidity and light level, there’s a vast range of recordings that date back to the 1970s. After all, the RNCM is primarily a space for performance, and clips of these reels can be found online too.

“We’ve got recordings of students practicing and recordings of large-scale concerts and orchestras, so that core collection of materials is so valuable and vast. Due to the evolving nature of recording technology, we have everything from magnetic reel to reel tapes to VHS, DAT tape, mini disk, CDs and digital recordings, all of which require different management procedures. You can’t just stick these things on a server and expect them to be fine, it’s a constant cycle of monitoring and managing.”

Heather is doing the best she can to manage a collection that ranges from Chinese Sanxians to digital audition tapes, and she feels “very lucky that the RNCM recognises how important it is to keep and store these things in the best way possible.”

So why isn’t it in a bloody museum that's easy to access?

As with a lot of archive material, the debate surrounding the whereabouts of these curiosities is a complicated one. For Heather, this archive is as much about preserving histories as it is about keeping current and future narratives alive. Maintaining and creating history at the same time.

Ultimately, Manchester should have a music museum, and not just one adorned with black and yellow stripes and a massive mural of Ian Brown. One that tells the story of the city's musical narrative from start to finish. The pieces at the RNCM are as much a reflection of Manchester’s music history as New Order and Oasis. Heather highlights, “Manchester’s music history started in the 1800s, and it only really took off with Sir Charles Hallé. He came from Germany and said ‘I can really do something here’.”

Manchester had a rapidly increasing population, and Hallé decided that having an orchestra here would bring not only enjoyment, but some sort of balance to the cities hectic industrialisation.

As Heather said “this ethos is such a Mancunian thing, and it carries all the way through to our politics and culture and the spirit of innovation that we’re famous for. It’s the same ethos that people like The Smiths and Oasis had, the same motivations were behind the rave movement for example, and Hallé toured like they did, brought music to the forefront of our identity, and enabled musical education to thrive in Manchester.”

Hallé-lujah

Hallé brought musical education to Manchester, created the Royal Manchester School of Music which was funded by the public, and we’ve never looked back. If there’s going to be a Manchester Music Museum, the collection should start with these charming objects sitting in the basement at the RNCM.

Heather also feels very determined that were the RNCM archive to go on display it should go somewhere deserving of it’s prestige. There’s a lot of technical and legal reasons as to why the collection couldn’t just go in a museum, but as a mark of pride, the RNCM loves showing off the collection to people that can come. If it were to be displayed somewhere else, “a spot like the Hulme Hippodrome renovation would be a dream, but mainly, the museum would have to be accessible and the collection would have to show off Manchester’s musical history as one long and ever-evolving narrative. We should show it all off with a bit of swag, because I think Tony Wilson's spirit would be angry otherwise.”

I wanna go

The archives at The Royal Northern College of Music can be viewed upon request, and Heather is an incredible tour guide. If you'd like to interact with the collections, book at least a week in advance via email or have a browse through the online catalogues, but I recommend going in person. You're provided with an opportunity to "hold history in your hands", and that doesn't happen very often.

To keep up to date with new acquisitions, collection quirks, displays and projects, follow the RNCM Archives on Twitter. Heather is also open to chat about material that could be of value to the collection or about other heritage and archive projects you think you could help with. Basically she's great, and so is the collection.

Follow Ellie-Jo on Instagram and Twitter

Read next: City curiosities: an alternative tour of Manchester Part One

Read again: Department: the most beautiful shop on Barlow Moor Road

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!