Can art really transform a city for the better? David Blake talks to Manchester Art Fair CEO, Thom Hetherington.

It feels appropriate to be meeting Thom Hetherington at a restaurant inside one of Manchester’s most dear artistic institutions, The Royal Exchange Theatre. Appropriate because Hetherington is the founder and CEO of both the Aviva Investors Manchester Art Fair and the Northern Restaurant and Bar Show, and because we’re here to talk about art, over food.

For the past few weeks we’ve been discussing Manchester’s so-called ‘cultural renaissance’ and the wider impact of art on the city. Where did this cultural renaissance come from? What constitutes a 'renaissance' anyway? And how can art transform a city's future?

Arts, culture, food and drink...who'd want to live in a city centre without those things?

There are of course countless studies into the wider benefits of art and culture on cities. Though most seem to boil down to these key points: 1. Arts and culture make cities better places to live, which attracts talent, ideas, innovation and so on. 2. A strong cultural offering brings in tourists and all their lovely money. 3. It creates jobs. 4. It makes people happy.

Manchester’s growing appreciation for the arts has certainly made Hetherington happy. In the decade since the art fair began (formerly named the Buy Art Fair), he and his team have helped shift over £4 million worth of art, whilst creating one of the largest and most exciting art fairs in the country.

“I’d say art and culture are now more visible, more accessible and more intrinsic to this city and its residents than it ever has been before, certainly in my lifetime,” says Hetherington. “That doesn’t mean it’s all sweetness and light of course, there’s still significant work to be done.”

Such as?

“Balancing development with continuing provision for the arts.”

There can be little doubt that there’s a correlation between culture and the number of cranes on Manchester’s skyline. Earlier this year a study by the Centre for Cities think tank ranked Manchester as the fastest growing population in the UK, up 149% between 2002 and 2015. Current estimates suggest there are around 50,000 people living in Manchester city centre. In the late 1990s there were just a few thousand.

As Hetherington points out, these people don’t simply move into the city centre to be closer to their place of work. “It's a vibrant and desirable environment, based around access to arts, culture, food and drink. No one would want to live in a city centre without those things. They tend to be at the vanguard of any city or neighbourhood on the up, after which everything else, including money, follows. I hesitate to use the word ‘gentrification’ as it’s rather contentious.”

I wince when I see a pub flattened or an artists’ studio displaced in the name of progress.

The term has certainly been getting a hard time at street-level and in the press of late (the current hand-wringing going on in Manchester’s Northern Quarter is a case in point). But isn’t gentrification, with the influx of new people and businesses and amenities and jobs and prosperity essential to sustaining a successful city? And isn't the dispersal of artistic communities into forgotten corners of the city a good thing? And anyway, neighbourhoods have always changed.

“This is an emotive and nuanced issue,” says Hetherington, cautiously. “For me the answer lies in balance. Anyone who, like me, grew up in the bleak, depopulated and barren Manchester of the 1970s and 80s can’t fail to be excited and proud that there is now so much going on and that people from all over the world want to come here.

“But, like many, I wince when I see a pub flattened or an artists’ studio displaced in the name of progress. That said, I have huge confidence in the resilience of this city’s burgeoning artistic community. I don’t for one minute believe it will be snuffed out merely because a building has been lost or because the dynamics of a certain area have shifted.”

Back to Manchester’s much publicised cultural renaissance. Doesn't the term ‘renaissance’ imply that there has been some sort of revival? In which case, when did this previous high cultural watermark occur?

“Back in the heyday of Victorian patronage of the arts,” says Hetherington, “when the city was one of the richest on Earth and the ‘Art Treasures of the United Kingdom’ fair held in Trafford Park was the largest art festival Britain had ever seen.”

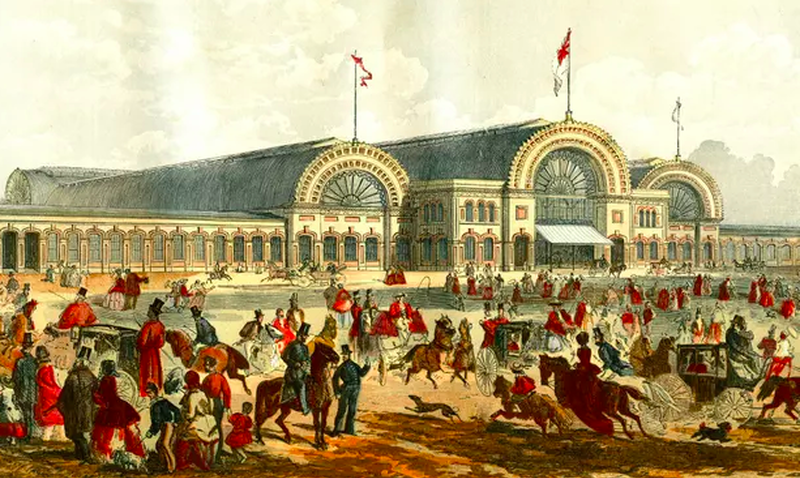

With an estimated 1.3 million visitors and 16,000 works, the 1857 art fair – housed in a 650 feet long, 200 feet wide iron and glass pavilion - remains to this day the largest ever held in this country, possibly the world. Friedrich Engels, who spent two decades in Manchester, wrote to his friend Karl Marx at the time: ‘Everyone up here is an art lover now and the talk is all of the pictures of the exhibition.”

The fair was a statement by the city, not just of its wealth, but also to show the world that Manchester was more than just chimneys and smoke and cotton. This was a city of art lovers and art enthusiasts. As one journalist later wrote: ‘1857 was a turning point in the history of art appreciation’.

So the Art Treasures exhibition paved the way for the artistic activity and creative confidence that would come to define Manchester. Though Hetherington says it's important we realise the city’s cultural reawakening has not been an “overnight success”, but rather has “almost two decades of strategy and graft behind it”.

“It started with the leadership of the city recognising that culture was important both to Mancunians’ everyday lives but also to drive tourism, with all the economic benefits that brings,” he says.

That commitment to culture-lead regeneration still remains high on the agenda in Town Hall. Just a few months ago, speaking following approval of Manchester's headline-grabbing £110m Factory arts centre project, council leader Sir Richard Leese said: "Culture and creativity have a critical role to play in Manchester’s future success – not just by inspiring ideas and imaginations but through creating opportunities and jobs."

If you’d have said twenty years ago that Manchester would be picked out by the New York Times as a globally significant tourist destination you’d have been laughed out of town

For Hetherington the tipping point was the £35m extension of the Manchester Art Gallery in 2002, which paved the way for the likes of Manchester International Festival (MIF), the extension of The Whitworth, the creation of HOME and the aforementioned Factory – which is being billed as the ‘flagship cultural venue for the North’.

Of course, these institutions don’t fill themselves, and Hetherington says it has taken dynamic individuals like Maria Balshaw (former director of the Whitworth, now Tate director), Dave Moutrey (director of HOME), Alex Poots (founding director of MIF) and Christine Cort (managing director, MIF) to drive the city’s cultural reputation forward.

This growing cultural muscle was recognised in 2015, when Manchester became the only UK city named in the New York Times annual ‘top places to visit’ list, thanks to a ‘flurry of cultural openings’. So can we assume that Manchester has, as Poots intimated in 2015, finally achieved status as a “globally important cultural city”?

“If you’d have said twenty years ago that Manchester would be picked out by the New York Times as a globally significant tourist destination you’d have been laughed out of town,” says Hetherington. “But it has and it is. I know this because we’re finding it easier to attract both international galleries and collectors to the art fair.”

Though, according to Hetherington, the job “isn’t done”. Which begs the questions: how much more needs to be done? How many more galleries, theatres and festivals do we really need?

“It’s impossible to put a number on it,” says Hetherington, “but I would just say more, as I believe we will find more and more Mancunians and visitors to fill them. The pace and scale of Manchester’s cultural renaissance is so notable that you can feel the direction of travel, you can sense the change happening around you.”

For the past few years, Hetherington says he has held up London's Frieze Week as a yardstick for his own art fair. "The art world is insane down there," he says, "rich, diverse, bursting with brilliance. Yes it evolves and yes it ebbs and flows, but it's essentially the same year after year. With Manchester though the city feels completely different every single year."

“For modern tourists, obsessed by Instagram and authenticity and being part of something real it’s quite intoxicating to be part of that cultural renaissance. They become part of it and they leave their mark," he adds.

And it's not just tourists who are pouring into Manchester to bask in the cultural glow. It’s the artists too. “We can benefit from the fact that London is so financially impossible, as a new generation of artists look to base themselves here."

Hetherington tells me a story of attending a fair in London when he spotted an artist, Evie O'Connor, represented by a gallery from Los Angeles. "The gallerist explained that after doing an MA at Glasgow School of Art everyone expected Evie to move to London, but she was firm that her art was informed by being in the North and that it was important for her to be based here. She's originally from Glossop, but returned to Manchester and is now based at Paradise Works in Salford.

"I'm hearing more and more stories like this," he adds, "but it's important that they're coming here because they want to, not because they have to."

Not that there'll be much need for arm twisting. Because right now, as was the case 160 years ago, it feels likes there's few better places to be.

Tell us a bit more about the Aviva Investors Manchester Art Fair...

How would you convince somebody who thinks 'art isn't for me' to buy something at MAF?

TH: "Firstly, I'd say that art is absolutely for everyone, and I think people often underestimate how much art affects them. The simple fact is that art it all about engagement and exposure, the more art you see, the more you form your own opinions on what you like and what you don’t like. The important thing to remember is that you’re never supposed to like all art. That’s perfectly fine. But I would urge everybody to ignore any perceived snobbery and to just get stuck in and to come to the fair. I guarantee that everyone who walks through that door will find at least one artist, or one piece, that grabs them."

Who should we be looking out for at the fair?

TH: "We’ve lots of local talent with artists such as Ian Rayer Smith, Jo Deas, Amanda Wigglesworth, Michelle Taube and Lee Herring exhibiting this year, but all the big names are represented too. Galleries will carry works by Damien Hirst, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Martin Creed, Harland Miller, David Shrigley, Sir Peter Blake, David Hockney and more. In addition, galleries will be coming from across the UK to Manchester, such as Arusha Gallery (Edinburgh) and Drang Gallery (Cornwall), joined by new exhibitors such as Curated by Amar Gallery (London) and Elastic Space (Salford). We are also proud that for the first time we have seven international galleries exhibiting in The Manchester Contemporary."

Many people know what to expect from MAF, but what about the Manchester Contemporary, what’s that all about?

TH: "The Manchester Contemporary runs alongside the Aviva Investors Manchester Art Fair – it’s in the same venue, so one ticket gets you into both fairs. It exists to provide a specific curated platform for artist-led spaces and galleries that champion critically engaged works from emerging artists. We have a new curator this year, Nat Pitt, so I will leave it to him to explain what people will find at this year’s edition:

“The Manchester Contemporary has gone from strength to strength over the last ten years, and now we are presenting our strongest roster of contemporary art galleries and artists to date. I have concentrated on bringing back key previous exhibitors alongside some new galleries, offering the best from across the UK and internationally, with new exhibitors coming from as near as Wakefield and as far afield as Berlin, Rotterdam and Caracas. As curator, I am hugely excited to bring these galleries to Manchester, making this a more accessible fair for the audience, collector and gallery alike and providing a unique, critically-engaged environment for viewing and buying art.”

You can find more info and tickets for the Aviva Investors Manchester Art Fair here. Open 10am to 6pm Saturday 13th Oct, 10am to 5pm Sunday 14th Oct at Manchester Central M2 3GX. Tickets £5 on the door.