Abandoned stations, vast housing blocks and the birth of a city centre monster - a pictorial snapshot of Greater Manchester in the seventies

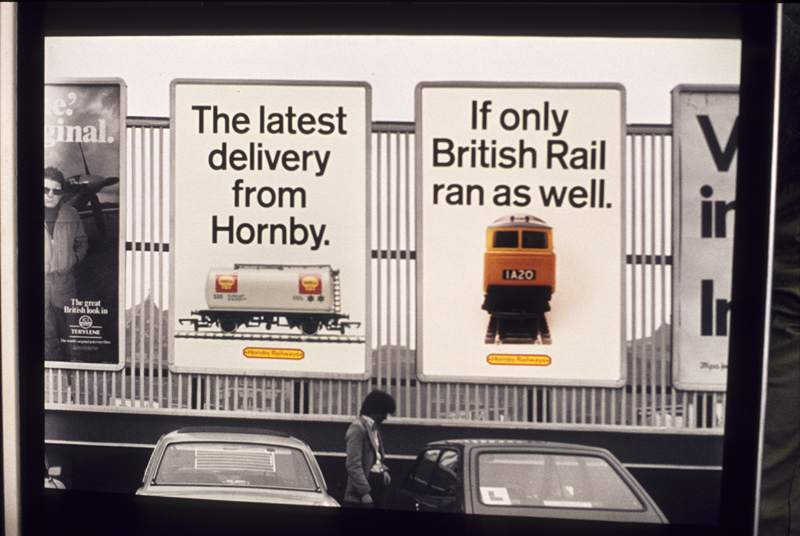

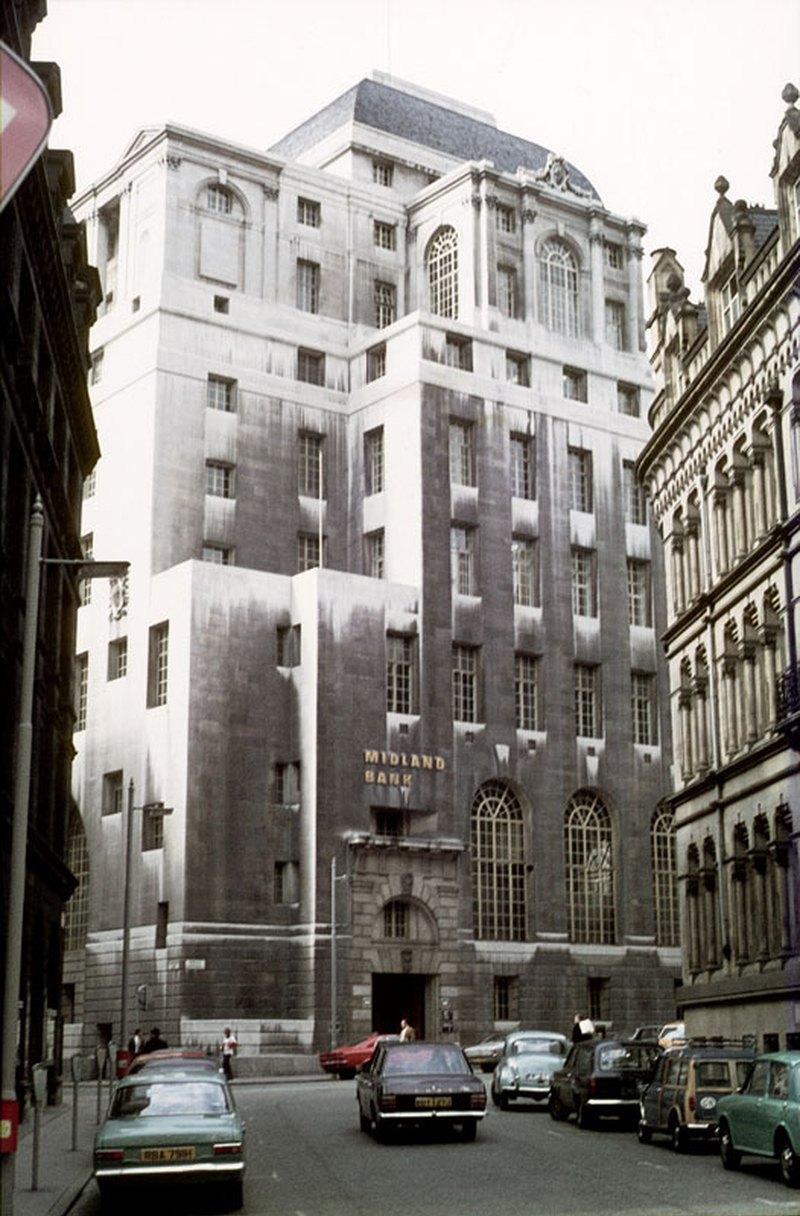

THE seventies was the decade of confusion, of a loss of direction, of new music and the arrival of a vast city centre monster. It’s ten years of a puzzle wrapped up in a riddle, of oil crises, three day weeks, power cuts, of macro-economic changes that revealed just how far British global influence had slipped from the heady days of Empire and industrial hegemony. It also revealed just how far other British cities had slipped behind their capital.

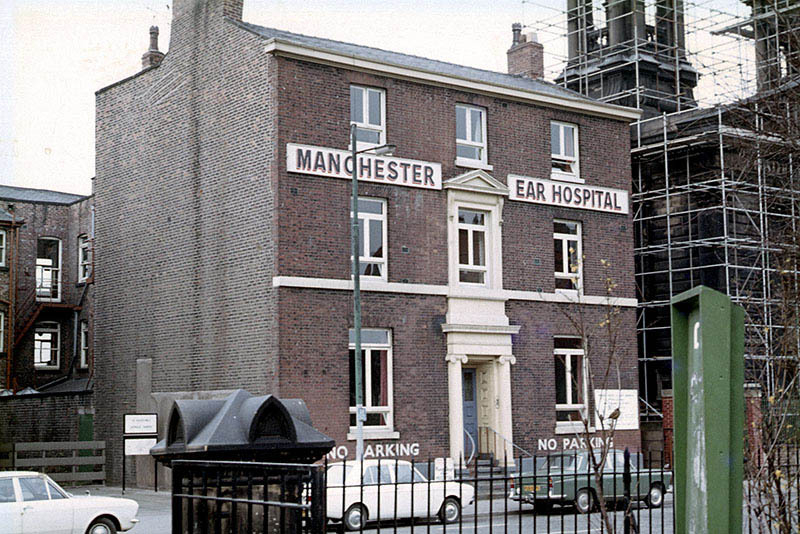

During the 1970s, the City Council lost most of its remaining key responsibilities. After WWII cities such as Manchester lost power over their gas and electric supply – and thus much of their income. The NHS did for the city's responsibility over local hospitals, while during the 70s all control of local transport was finally taken and Manchester’s famous red buses became a grotesque mess of pop orange and brown under a broader transport authority.

In 1974, Greater Manchester County was created from south-east Lancashire and north east Cheshire. Thus the city of Manchester lost power over its police force and fire services. With the creation of the North West Water Authority it also lost its management of water and sewage services. Even the airport was taken out of Manchester’s hands to be shared by the new Greater Manchester authority.

These seemed like logical steps at the time, rationalising multifarious authorities under single control. In hindsight, much of the well-intentioned measures diminished the big cities and emphasised the capital’s brutal dominance.

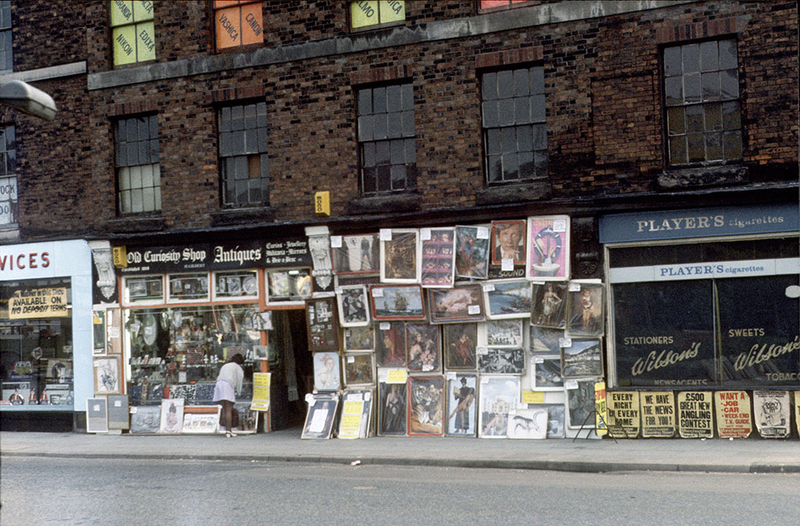

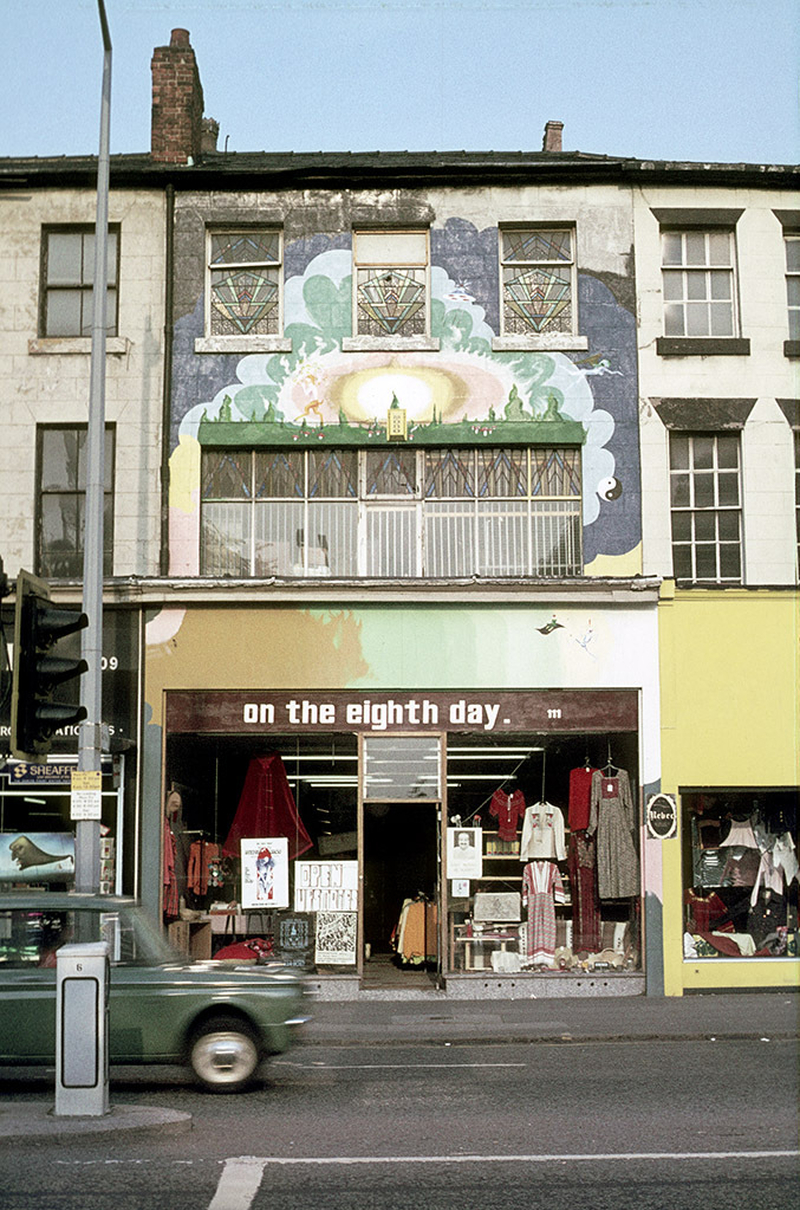

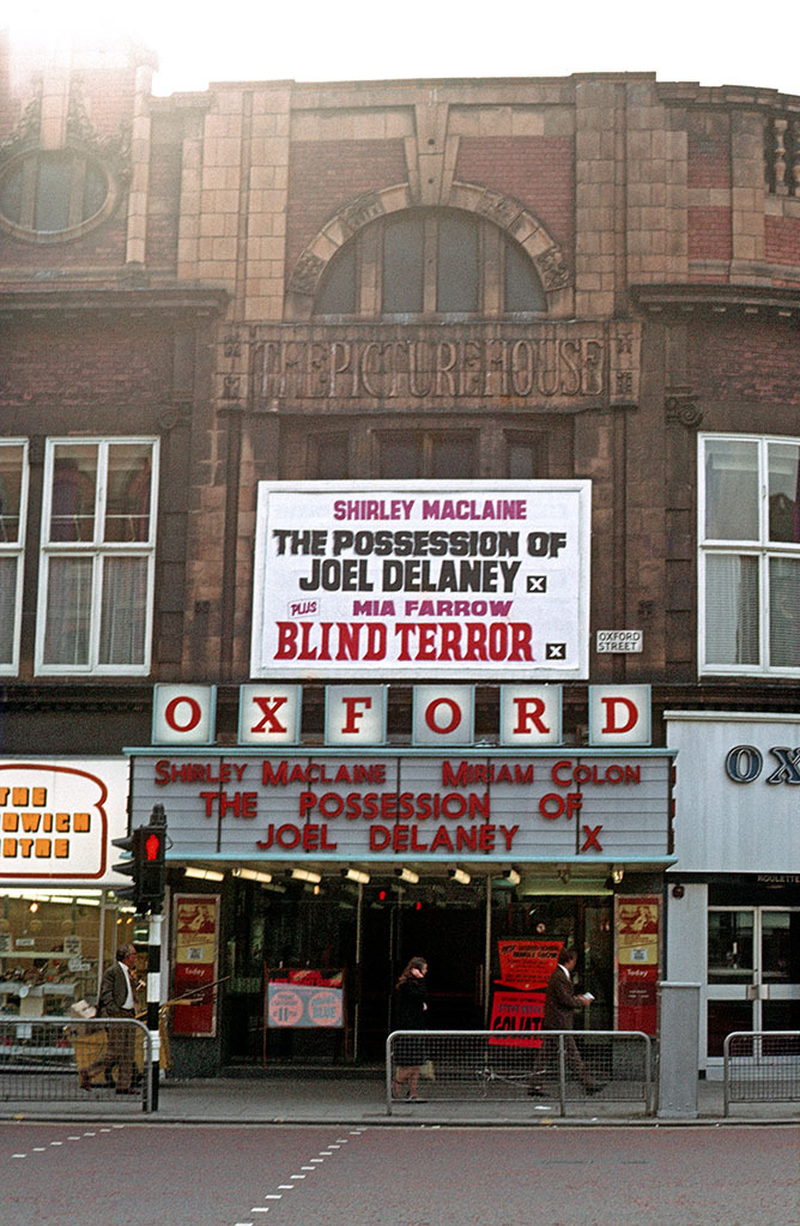

Meanwhile, the Arndale Centre arrived, a fat jaundice-coloured mother hen squatting upon a network of fascinating, if at the time rundown, streets. As The Guardian commented, the building was so aggressive it was hard to know whether to 'shop in it or lay siege to it'.

Today those little streets might have been a fascinating array of small businesses and bars, another Northern Quarter, while Oldham Street, instead of being effectively closed down by the Arndale for twenty five years, might have remained a key retail street. Who knows?

It was during the 70s that the M62 motorway was completed, but also when Manchester Ship Canal began a steep decline at its headwaters in Salford and Trafford as container traffic began to make it unviable.

Slum clearance was declared over, only for the buildings which had replaced the slums to start rapidly crumbling in turn. Hulme Crescents, constructed in 1972, was the largest public housing development in Europe, and arguably its worst.

The slum clearances officially being over didn't stop needless demolition of classic Manchester buildings, such as the opulent Oxford pub (pictured below) opposite the Palace Theatre, which became a car park until the noughties.

Manchester United, meanwhile, dropped from European Champions in 1968 into the old Second Division (now the Championship) for a season in '74-'75. City drifted unspectacularly.

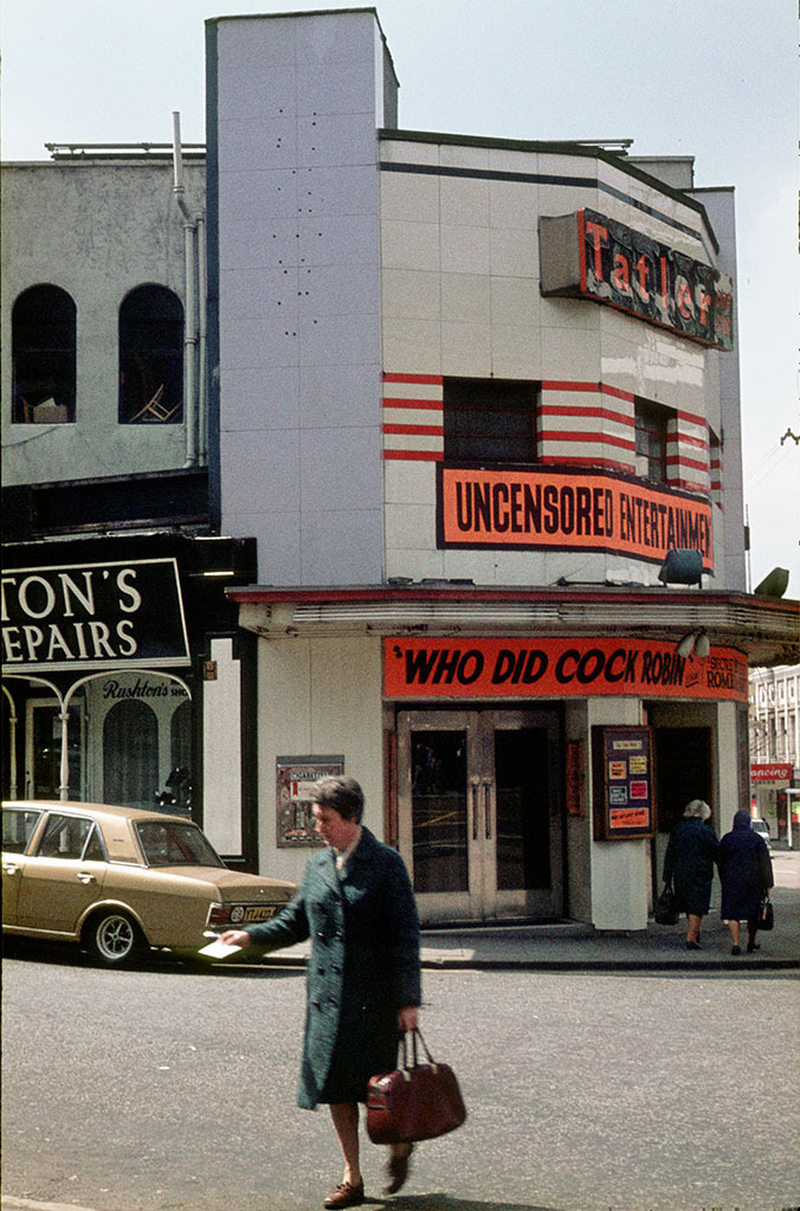

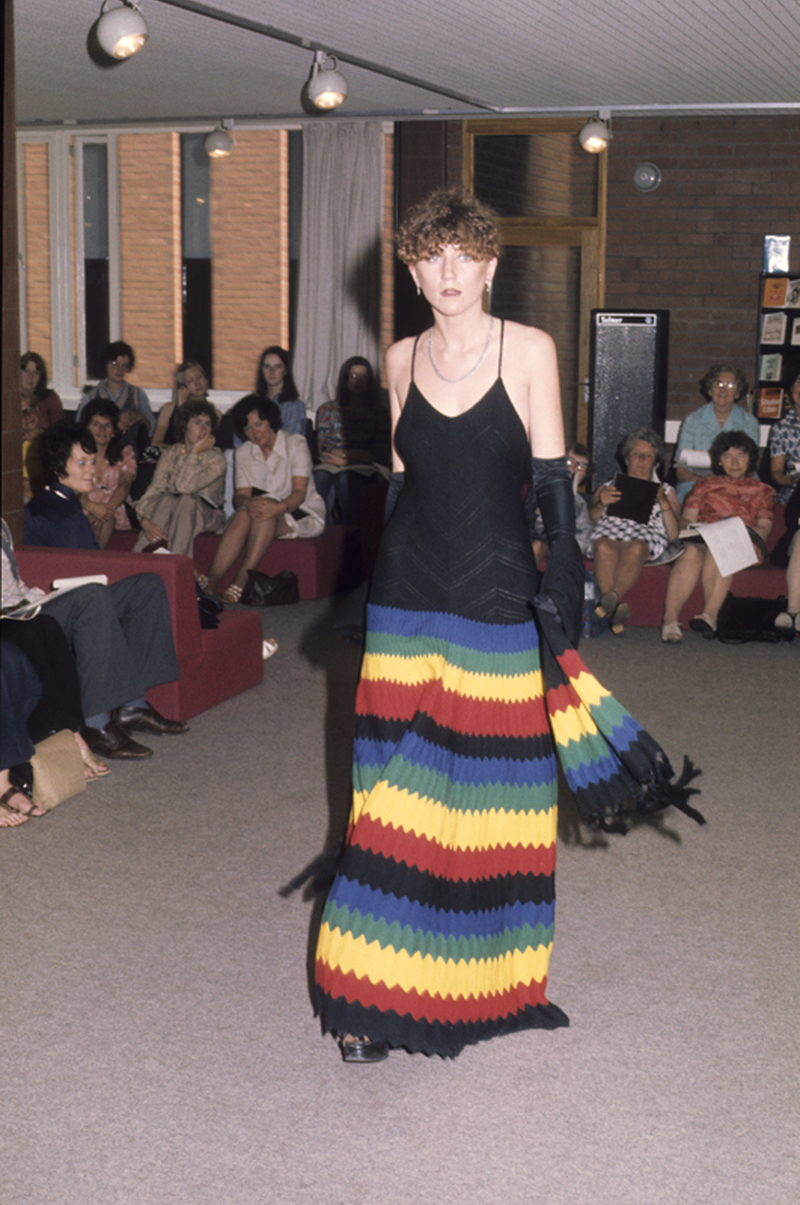

Music offered distraction. There was a lot to make a song and dance about on the scene. The club scene in Manchester in the early 70s was dominated by places such as Rotters, Fagins, Stringfellows, Placemate 7s, and (for those of a little more Bohemian character) Pips, under the Corn Exchange.

Manchester bands and acts such as 10cc, Elkie Brooks, Sweet Sensation and Sad Cafe hit the charts, while ex-pat Manc boys The Bee Gees boosted chest hair, big hair, medallions and discooooooooo. Northern Soul became an established phenomenon.

Don't forget to read: This is Manchester: 90 photos from the 1960s

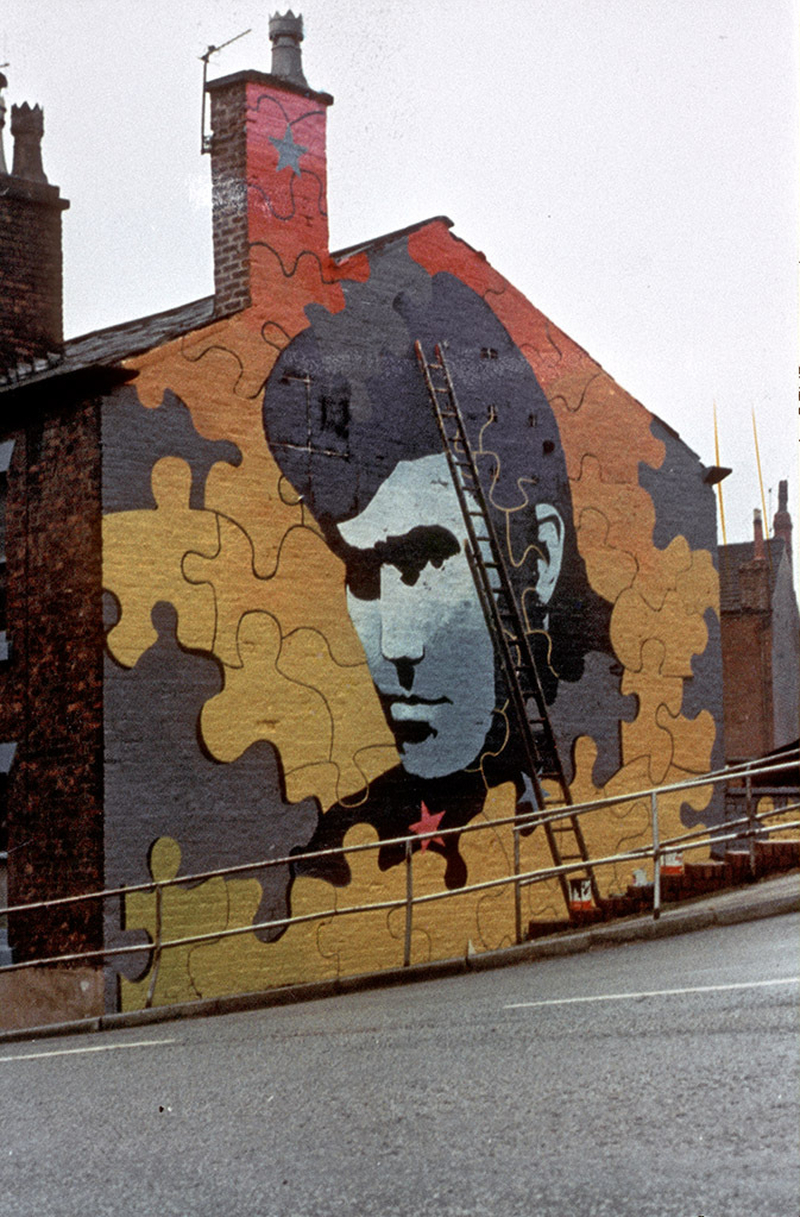

But something else was bubbling under, and in a dark, smoke-blackened, declining city a new idea of music was forming with a whole scene and its own magazine, New Manchester Review. In 1976, the Buzzcocks hosted the Sex Pistols in the Lesser Free Trade Hall - the legendary year zero for a significant musical movement. Two years later, the mercurial but brilliant Tony Wilson started Factory Records with Alan Erasmus. The band Joy Division, signed to Factory, became the totemic Manchester sound of the time.

Along with the growth of the music scene there was the beginnings of a turn around in the appreciation of the significant role Manchester had played in the creation of the modern world.

When British Rail announced the closure of the Liverpool Road Depot, a campaign began to save the oldest passenger railway station in the world, part of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway from 1830. This would, in the 80s, form the site for the Museum of Science and Industry. Castlefield began to be generally recognised as a place of immense industrial and historical importance.

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher became the nation’s polarising Conservative Prime Minister, and as the 70s, the decade of confusion, came to an end, the nation and the city were set for the 80s, and another period of uncertainty, retrenchment, creativity and evolution.

In 1976 the aforementioned Tony Wilson had fronted a music show of his making at Granada. It was called So it goes.

Exactly.

Words by Jonathan Schofield. All images from MMU archive.

Don't forget to check out This is Manchester 1960s. The 1980s edition will follow soon...

Images from the Visual Resources Collection at Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections. All rights reserved.