Jonathan Schofield explores the real reason for that superb ship on buildings and football badges

Sink that ship: pound it with emotive language

Thursday 13 April early evening and I was sat with a friend enjoying a quiet drink on a trip out of Manchester in Halifax’s memorial to the benefits of trade: Piece Hall. Ah trade, it doesn't half bring the world together.

Ping.

Guardian journalist Simon Hattenstone was on Twitter urgently asking me to follow him so he could ask a couple of questions through direct messaging.

Nobody has been covering anything up here, there has been no omerta. Let's interpret that ship as a beautiful symbol for a modern city of 200 languages

They turned out to be very bizarre questions. Here they are grammatically tidied up.

‘I just read your piece on the symbolic ship in Manchester and just wanted to check whether all the places you name that have been redeveloped (Kimpton Clocktower Hotel and Hotel Gotham) still carry the coat of arms/ship. And (daft question I know, but just triple checking), is it still the council's coat of arms? I am writing a piece for The Guardian about whether we should still be celebrating the ship as it's so closely associated with imported cotton produced by slave labour.’ (I’m assuming it was this piece on Confidentials.com he was referring to or one adapted from it.)

I was bemused. Did Hattenstone really need to ask whether the ship was still on the coat of arms? I believe internet searches are very fast these days.

What was this about the ships being closely associated with cotton produced by slave labour?

And did he really believe listed buildings such as The Kimpton Clock Tower Hotel should have scaffolding erected and the Manchester ships all chipped off, did he think that was allowed on listed buildings? Perhaps he thought they could be replaced with an emoji heart.

I asked him to ring me rather than have me laboriously reply by DM. He called. I said the whole premise of this close association was ridiculous and answered his questions.

The man was on the hunt though, you could smell it down the phone. Simon Hattenstone was a journalist who wanted to claim some guilt with a shock-horror-wham-bam idea and he wasn’t going to let the facts get in the way of the headline.

The story appeared on Wednesday 19 April, 2,580 words long (a bit longer than this one), under a provoking red top headline screaming ‘Abandon ship: does this symbol of slavery shame Manchester and its football clubs?’ The next lines were: ‘A three-masted vessel adorns the city’s buildings and both teams’ crests. But is it an emblem of a crime against humanity?’

The answer to the two questions there is dead simple. No. The ship on the coat of arms is not a symbol of slavery, nor does it shame Manchester and its football clubs and it is in no way an emblem of a crime against humanity. Principally it’s a ship doing what ships do: good stuff generally, where would we be as a species without them?

The words in Hattenstone’s bizarre article linking the football clubs through the ship to slavery were calculated, crazy and cynical, an attempt to give the non-story, his mucky lie, greater legs. Well, Mr Hattenstone, you got your wish.

The Manchester clubs and that ship

Manchester United and Manchester City (under different names) were formed decades after the abolition of both the trade and the keeping of slaves in the British Empire and the ship was simply adopted to show affiliation to the city of their origin by incorporating a symbol from the Manchester coat of arms.

But not at the start. At the clubs’ inception the ship wasn’t on their crests because they didn’t have crests. The present designs weren’t adopted until the 1960s and 1970s.

The teams wore the full coat of arms of Manchester in FA Cup Finals before then or when representing the city in European competitions from the 1950s but there was no crest that we see today on their shirts. Some stretch to say the Manchester clubs should be ashamed or even remove the ships on the badges given they arrived 120 years or more after the coat of arms in 1842 and were included to express a common identity with their home city. Instead of shameful isn't that rather lovely: identity, common purpose and all that.

Who and why was that ship on the coat of arms?

What about the ship on the city coat of arms then? As stated above it arrived in 1842, four years after Manchester had been properly incorporated as a borough. A principal campaigner for borough status was Richard Cobden, a staunch abolitionist.

Richard Cobden, along with John Bright, were members of the Manchester-based Anti-Corn Law League. The campaign for borough status and the Anti-Corn Law League were explicitly battles against entrenched privilege.

The Anti-Corn law League would in time become a Manchester-led Free Trade movement, extolling the idea that if businesses and people could trade freely across the globe without government interference then living standards would rise, freedoms would advance, shorn of doctrinaire nationalism.

As Cobden would say in 1846 in Manchester: ‘(With free trade) the motive for large and mighty empires, for gigantic armies and great navies, for those materials that are used for the destruction of rewards of labour, will die away’.

John Bright was another fierce abolitionist.

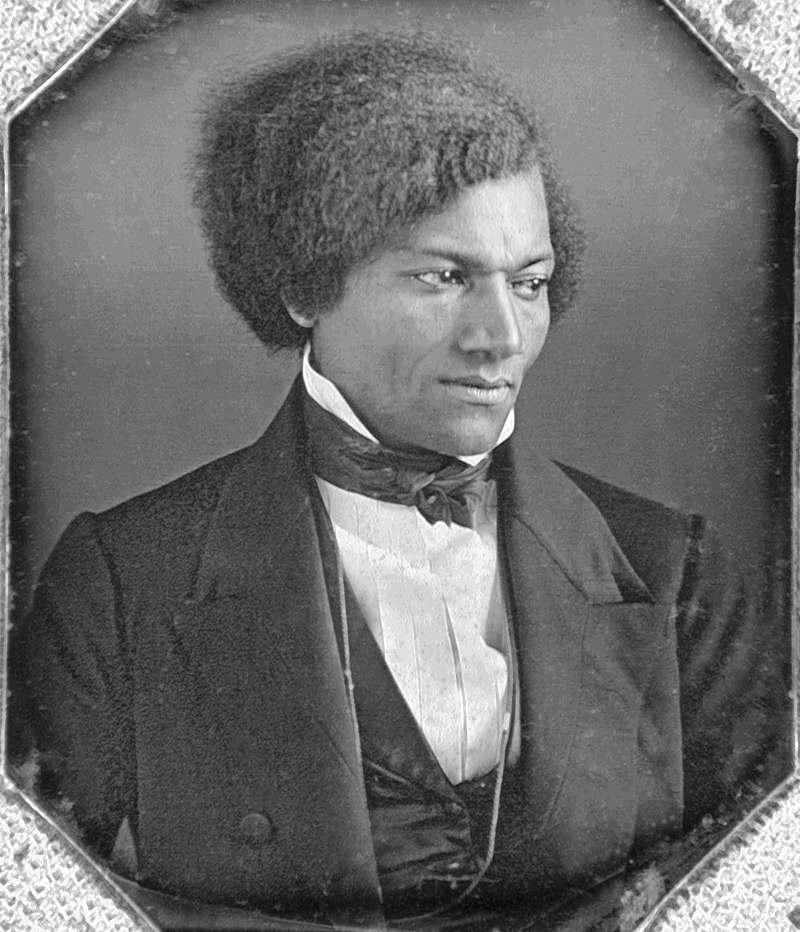

He would become Manchester’s MP in 1847 for ten years. Three years after the adoption of the city coat of arms with its non-controversial ship he hosted escaped slave Frederick Douglass. Douglass in his autobiography would write: “I was a welcome guest at the home of Mr. Bright in Rochdale and treated as a friend and brother.”

From August 1846 a campaign was run in Britain to buy Douglass’ freedom, led by Quakers, in particular Ellen Richardson. As David Thompson wrote on the Black Lives Matter website in 2022: ‘As a result of Douglass’ stay with John Bright in Rochdale, Bright immediately contributed one-third of the money needed to purchase Douglass from his American slaveholder. In October of 1846, Douglass arrived in Rochdale a fugitive slave. With Bright’s large contribution, however, Douglass left Rochdale about to become a free man. Ellen Richardson wrote that with the generous gift from Bright, they were certainly going to have the funds they needed to buy Douglass’s freedom from slavery.’

Cobden and Bright were at the heart of Manchester’s politics in 1842.

Does anybody think there was ever a conversation between them and others in which somebody piped up with: “Hey, do you know that new coat of arms we’re getting, well, I know we’re anti-slavery and have campaigned against it and entrenched privilege but let’s put a ship on the thing to celebrate slavery shall we? If nothing else it’ll enable the London-based Manchester Guardian in 181 years to flaunt righteous indignation. Oh and by the way who are these Manchester City and Manchester United things, never heard of them?”

Official Manchester histories over the decades have generally used a similar form of words to these by WH Shercliff in N Frangopulo’s book Rich Inheritance: a Guide to the History of Manchester (1964). ‘Above the shield is a ship in full sail representing commercial enterprise and Manchester’s links with the sea.’

The ship is clearly a positive symbol. It tells a story of a city with an international outlook, not one that restricts itself to a local, regional or even national viewpoint. Trade embraces the world and makes the world better it clearly and categorically states. “Arbitration is more just, rational and humane than resort to the sword,” said Cobden. The ship is a symbol of peace and hope.

Ships carried slave-picked cotton - yes and lots of other things

But, just a minute, says Hattenstone in his article, ships carried slave-picked raw cotton to Liverpool and from there it was carried to Manchester by rail and canal (not the Ship Canal which arrived fifty two years after the coat of arms). In many of the factories owned by abolitionists this tarnished product was turned into cloth. Absolutely true.

The double-think was recognised at the time by people such as Richard Cobden. Terry Wyke writing in Revealing Histories quotes Cobden opining how: ‘In the first place the thing is inconsistent, and in the next it is hypocritical’.

But the ship on the Manchester coat of arms is any ship doing any and all business. To say it’s just a slave-picked cotton delivery tool pure and simple is plain silly and to say that was the intention, even unconsciously, for its inclusion on the Manchester crest is even sillier given the evidence stated above. The ship might be sailing out from Britain as well as sailing in, it might be delivering engineering components to France or emigrants to the USA or timber from Scandinavia into the UK. In the end, the ship is about making connections across the world not destroying them, it’s also about the traffic of ideas such as Free Trade. It is categorically not an ‘emblem of a crime against humanity’ it is a ship going about its business.

The heart of the Guardian matter

But let’s moor the bloody ship for a moment.

Let’s consider a general point about The Guardian’s series of articles concerning Manchester’s links to slavery. A point articulated on several occasions by people such as Gary Younge, David Olusoga and others claims that Manchester has buried its links to the slave trade under lots of positive messages concerning the 1788 petition to Parliament asking for the slave trade to be abolished, invitations to black figures such Douglass and Sarah Parker Remond, the support for the Union not the Confederacy during the American Civil War, the Lincoln statue and so forth.

This simply isn’t true.

As far as I’m concerned historians, commentators and tour guides in Manchester have never shied away from the fact that Manchester took slave-picked cotton from America before the conclusion of the American Civil War.

I recall taking The Guardian and Observer chiefs including Guardian editor Kath Viner, on a tour in 2015 and talking about the Thomas Clarkson speech in 1787 which led to that petition in 1788. I also talked about the hypocrisy of individuals being abolitionists while using slave-picked cotton. I know I talked about this because I say it every single time I do tours on this thread of history with slavery, cotton, abolition or even when marking the fifth Pan-African Congress in the city in 1945.

I want more information. That’s why the two-year research conducted by Cassandra Gooptar and others for The Guardian has delivered new information which can now be included in the history of the city. Evidence of direct ownership of slaves by Mancunian individuals or businesses is thin. The Gregs of Styal were owners, that was known, but that George Philips, one of the sponsors of the first Guardian newspaper in 1821, owned slaves is fresh information and valuable. Any research that delivers a clearer picture of history is very welcome.

The Guardian clearly thinks there should be more explicit teaching of the subject in Manchester’s schools. Agreed. But just as it has to be recognised (and I think it always has) that Manchester (along with other European countries with cotton production) took slave-picked cotton to make sure we get ‘the whole picture’ then we must include all the positive actions of the good human people (white or black we are all human) involved in the story should be taught as well. Balance is everything. These would be great lessons.

I think this is where the whole Guardian self-exposé starts to unravel.

Read the articles and there’s a clear link being made from slave ownership to production using a slave picked product to the general trade and economy and Britain, the Empire and by extension the whole Western domination of global trade until recent times. Essentially, that fine new research aside, The Guardian in these articles has written a socialist, even Marxist, critique of nineteenth century Britain. Fine, that’s increasingly The Guardian tone in these hyper-partisan times. But don’t pretend it’s clear-headed impartial scholarly interpretation.

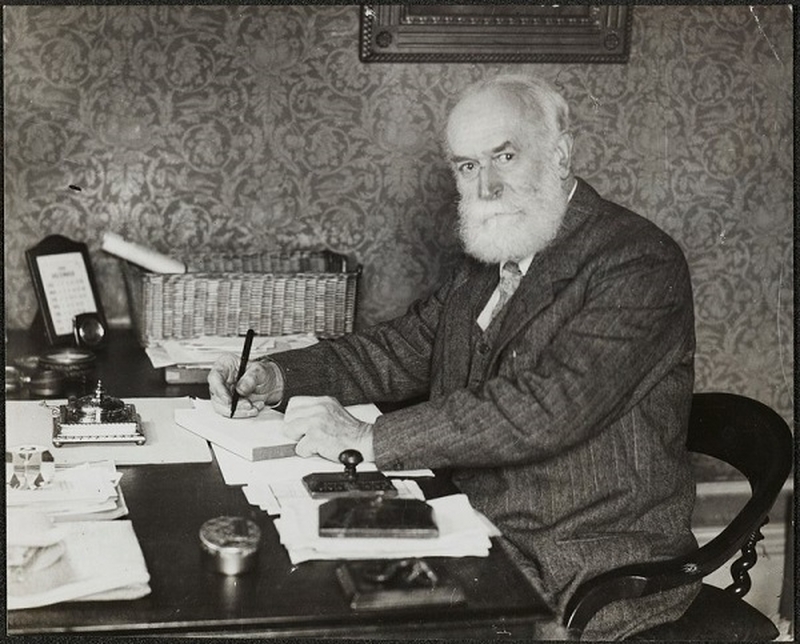

Worse, the Hattenstone article in the paper betrays the words of 57-year editor, Charles Prestwich Scott, when he defined what a newspaper should be in 1921, a hundred years after John Edward Taylor founded The Manchester Guardian.

CP Scott wrote: "Comment is free, but facts are sacred. Propaganda, so-called, by this means, is hateful. The voice of opponents no less than that of friends has a right to be heard. Comment also is justly subject to a self-imposed restraint. It is well to be frank; it is even better to be fair.”

The ship is a beautiful symbol perfect for the modern city

Hattenstone's story is a classic case of bad faith journalism where there is an idea that the writer fails to prove within his article, but just keeps repeating the claim, like a child, hoping it will stick.

Worse, the sub-editors (or maybe the author) then slap an incendiary headline that conflates an 1842 coat of arms with famous football teams to get clicks on its website, and sales in the newsagents. What was that from CP Scott again? Oh yeah: “it is well to be frank; it is even better to be fair.”

Following the publication of the article and given I had been quoted in there I spent the following day fielding requests for an interview from seven media outlets including a producer from whatever snarling show Piers Morgan hosts. I talked to The Times and that was it.

I shouldn’t have needed to talk to anybody.

What Hattenstone did was take a positive and benign symbol from a coat of arms produced in a mood of optimism following the creation of Manchester as proper borough and roast it. A century or more later that symbol was reused on badges that link blue and red halves of the city, a rare achievement indeed, but he ignored the facts to air a twisted theory.

Surely, we want commentators pouring water on the endlessly tedious and invidious culture wars rather than dousing them in oil. Hattenstone has made something that was not even a real discussion point into bitter and artificially constructed row. He's misread the mood in a city which after the 2017 terrorist attack showed its togetherness.

The ship on the Manchester coat of arms, carved proudly on city buildings and etched on the badges of Manchester City and United has never been about slavery.

Nobody has been covering anything up here, there has been no omerta.

Let's interpret that ship as a beautiful symbol for a modern city in which 200 languages are spoken. Let's take it is as a beautiful symbol of a city in 2023, international in character, shunning parochialism and looking forward.

City and United should sport their badges with pride, their teams are international and their fans are international: an international sailing ship is just the ticket.

Hattenstone writes: ‘Once seen, the ship can’t be unseen’. See it Simon, it’s much more than the cruel definition you’ve given it. Open your eyes. It's wonderful, positive. Shed the guilt. That badge of Manchester City you received as a 'little boy' is all right. Time to grow up.

Jonathan Schofield has written several books which include elements of this story and also runs tours on the theme. This year these will take place at 5pm on Saturday 29 April and 10.30am on Saturday 28 October.

If you liked this story you might also like:

Symbolically Manchester: more than just the bee

Short history of Manchester: Americans, slavery, fellowship

The Manchester Congress that changed Africa

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!