Jonathan Schofield tells the remarkable story of Mayfield Baths freestyle

Graham Mottershead, project manager at Salford Archaeology, summed it all up: “The Mayfield bathhouse is a fascinating example of the social and public health advancements that came about during the industrial revolution. As the city’s population boomed with factory workers, crowded and substandard living conditions gave rise to the spread of cholera and typhoid. For those living and working around Mayfield the Mayfield Baths would have been a vital source of cleanliness and hygiene."

Sanitation and pandemics. Wash your hands now, take a bath then. History, once again, proves cyclical.

A site which provided valuable public amenity will once again provide valuable public amenity as a park

Mottershead's excavations on the future site of the 6.5-acre Mayfield Park have brought together some fascinating finds and tantalising images of one of the region's earliest public baths from 1857. It's fitting and typical that the imaginative developer of Mayfield, U+I, intends to keep the lovely blue tiles and reuse them somewhere on the 24-acre site. It is also fitting that a public baths will become a public park.

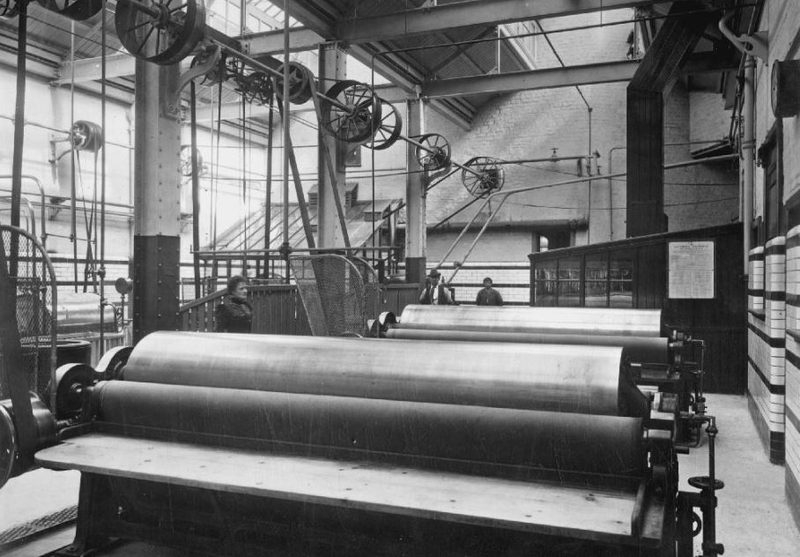

The patterned tiles found in the excavations include stylised cotton flowers. These were placed in the pools at a time when Manchester was the leading global power in the textile trade. The money for the baths largely came from that too.

The baths arrived via The Manchester and Salford Baths and Laundries Company (MSBLC). MSBLC was set up in June 1855 by Benjamin Nicholls, Mayor of Manchester, Joseph Heron, the Town Clerk (in 2019, that position has the more self-conscious title of Chief Executive) and William Neild, the owner of the neighbouring Mayfield Print Works, at that time one of the world's most famous industrial brands.

MSBLC was a philanthropic company. The Baths and Wash-house Act (1846) gave local authorities the power to borrow public money in order to erect public washing, bathing and laundry facilities, and in later years, swimming pools for ‘the labouring classes’.

Greater cleanliness and better general sanitation had been an ambition of British towns and cities since the cholera epidemics of the 1830s. Yet municipal government was in its infancy in the mid-1800s and often hadn’t the resources to complete all it desired, thus the gap was filled by this type of philanthropic enterprise.

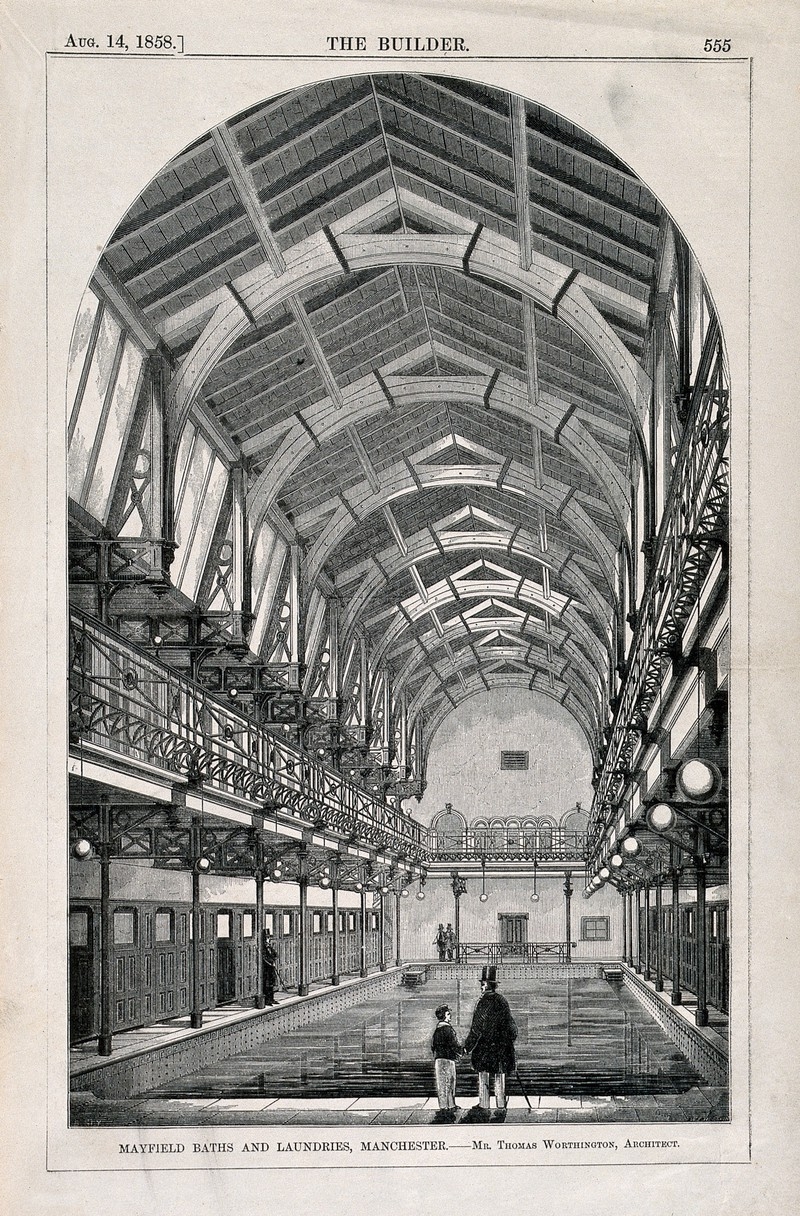

The architect chosen to build the first of the MSBLC buildings was Thomas Worthington. He was one of Manchester’s most prolific Victorian architects.

His buildings include the City Police Courts (now Crown Courts) on Aytoun Street, the Unitarian Memorial Hall (now Albert’s Chop House), numerous warehouses and houses, and pioneering hospitals such as Chorlton Union Hospital (now apartments) on Nell Lane. He designed Greengate Baths in Salford first for MSBLC and then turned to Mayfield Baths.

Worthington is perhaps most famous in Manchester for designing the Albert Memorial in Albert Square which was in turn copied by Gilbert Scott for his Hyde Park memorial to Albert.

Both the Greengate and Mayfield Baths were designed in an Italianate style, with regular windows and inside 'Roman detailing' in the main public spaces. One of the leading citizens of the time, the engineer William Fairbairn, said they ‘were likely to be examples to other cities in the kingdom’.

The cost of the baths was £10,000, admission was 6d for first class, 2d for second. The main swimming pools, first and second class, and a third for females, were 63ft (almost 20m) in length and 25ft (7.6m) wide.

Later, a ‘penny pool’ was added to allow boys to swim for a small amount of money but this was abandoned after the 1870s and the pool became a subscription-only baths as it was complained that boys were hanging around the nearby streets begging for money to enter the baths.

There are many interesting stories about the baths. George Poulton is at the centre of several and will be commemorated in the name of a 75,900 sq ft commercial building to be constructed on the Mayfield site. He deserves it.

Poulton was the premier ‘natationist’ of his day, an advocate of swimming. Some of his promotional techniques are eye-popping.

As the Manchester Guardian reports: In July, 1859, when 'suffering somewhat from a cold, he went through a performance with his usual skill and concluded to the seeming great delight of the numerous spectators, by eating a sponge cake, drinking a bottle of milk and smoking a pipe, whilst totally immersed in water.’

In subsequent visits Poulton would ‘give some fine specimens of scientific swimming and floating, illustrating a dead man, ‘The Crucifix’, ‘The Dying Gladiator’, turned eight summersaults in the water without touching the bottom. He was of such an amphibious nature that the water was as much his element as terra firma.’

In 1877 the baths were formally taken under the direct control of Manchester Corporation but it was Robert Crawshaw in 1900 who really added lustre to the story of Mayfield Baths. We've already told the story here on Manchester Confidential, but here's a quick summary.

Manchester was the centre of British water-polo at that time, so Manchester-based teams and players, including Mayfield's Crawshaw, made up the British Olympic team representing the country at the 1900 Paris Olympics.

The team not only won gold comprehensively, they wiped the pool floor with the opposition yet managed to conclude with an act of lovely nobility. The quarter-final they won 12-0, the semi-final they won 10-1 and in the final, they triumphed 7-2 in front of 5.000 spectators, but they limited the number of shots on goal to avoid humiliating their opponent. In subsequent Olympics, they would win two more golds.

The story of Mayfield Baths ended violently.

In the Christmas blitz of 1940 it was hit by a high explosive bomb and several incendiaries. It was never repaired, instead it was demolished and the rubble used to fill in the pools. These have now been rediscovered by the University of Salford archaeologists.

It's a happy reflection of Mayfield Baths' past that the site which for almost 100 years provided a valuable public amenity will once again provide a valuable public amenity; this time as a much needed city centre park.

What goes around doesn't always come around but in this instance we have a welcome example of an aphorism proving correct.