Jonathan Schofield on whether there’s a precedent for potential Brexiteer violence

THE gilets jaunes on Manchester’s streets burning cars, smashing shop windows, barricades rising, stones and petrol bombs thrown: a crowd turned mob in protest against ‘a betrayal of democracy’. London's burning.

Iain Duncan Smith, Michael Gove and other Brexiteers have warned that should there be a second referendum, which results in a remain vote, the streets will erupt, civil unrest will stalk the country.

But is there any precedent for this in Manchester’s long, long history of protest? Previous expressions of dissent seem to fall into several categories.

The main category is the demonstration and march. In Manchester these have generally been peaceful and the violent exceptions have come about through a particular reason, more of which later.

The large number of older people who voted leave aren’t likely to kick-off too much

There have been hundreds of mass rallies in the city. Here are a few. In 2013, 50,000 demonstrated during the Conservative Party conference over NHS reform and austerity. There have been much smaller anti-war protests, latterly about British involvement in Syria, although the biggest, organised by the Stop the War coalition, was the 10,000 who turned up in 2003 during the Iraq War.

In 1988, 20,000, turned out for an anti-Clause 28 demonstration. This was to protest the ill-conceived legislation from the Margaret Thatcher government against governmental agencies and local authorities which ‘intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.’ Celebrities such as Ian McKellan and Jimmy Somerville joined the occasion.

Push back further into history, demonstrations leap out from all over, including relatively small scale Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament gatherings in the early 1960s back to the far bigger demonstrations around the General Strike in May 1926. Back again, and you have a many thousands strong Suffragette/Suffragist demonstration and march from Stevenson Square to Alexandra Park in 1908. In 1892 the first Labour Day walk took place on 1 May, walking the same route with as many as 60,000 in the procession. The demands made during speeches were all about an improvement of working conditions and expansion of the franchise.

It would become tedious to catalogue more of these peaceful, usually celebratory, demonstrations and rallies in Manchester. What about the times things turned ugly? In Manchester, over-reaction by the authorities is usually the cause.

The Peterloo Massacre of 1819 is the most famous of these and involved magistrates, either under instruction or through panic, ordering the military to arrest the main speaker, Henry Hunt, and disperse the crowd. It’s clear that if that order had never been given fifteen people wouldn’t have died and hundreds wouldn’t have been injured. People had met to call for the vote and representation and the organisers had expressly requested they come unarmed and in peace.

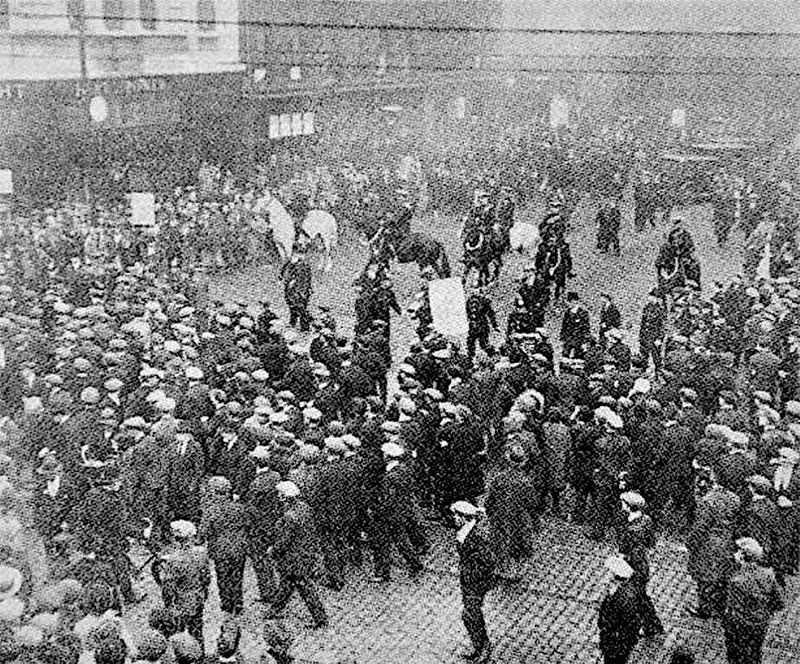

Similarly the Plug Riots of 1842 turned nasty because the authorities were at fault. The riots were part of a General Strike, again about the lack of the vote and also work conditions, and were arranged by The Chartists. The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel favoured a non-intervention approach, but the Duke of Wellington argued for troops to be sent in to deal with the strikers, and eventually he got his way. Let’s leap forward again to 1908 when a demonstration by the unemployed in Manchester was waylaid by the police in an attempt to disperse it and running fights broke out across the city centre, although as one of the leaders, Leopold Fleetwood, proudly claimed, ‘no windows were broken’, in other words no property was attacked.

The so-called Battle of Bexley Square in 1931 was more violent again, and involved thousands protesting in Salford during the height of the Great Depression about the dreaded means test that was removing unemployment benefit from a very poor population. This was organised by the Salford National Unemployed Workers' Movement and again violence flared when the police charged the crowd.

So what about other incidents of violence and civil unrest? Two occasions standout, the Moss Side riots in 1981 and the city centre riot in 2011, although only the first could really be categorised as a riot. The main ingredients in 1981 were racial tension and mass unemployment, particularly amongst black youth. The early 1980s saw the highest unemployment since the 1930s. The anger of the mainly youthful rioters, proper gilets jaunes action, caused widespread destruction of property. At one point more than 1,000 rioters besieged Moss Side Police Station. Twelve police vehicles were burned and an officer was shot in the leg by a crossbow bolt. It was quelled by the use of new police tactics and a massive show of police manpower the following night.

The 2011 ‘riot’ was in some ways pathetic. I was there on the streets watching as youths gathered and eventually took over much of the city centre in a copy cat riot to the early ones in London. If unemployment was a factor this time it was hard to tell, it seemed more one of boredom and a pretext to cause trouble. Indeed, rather than any political expression of anger, the main motive seemed to simply loot shops. This was an occasion where early police action would have stopped the couple of hundred young people in their tracks.

In view of the examples above it’s hard to find any precedent for the type of yellow jacket violence we have seen in France in December. It simply isn’t in Manchester's, nor the UK’s, tradition. Protest? Absolutely. But mass violence? Not really, especially when the dynamics of Brexit are taken into account and the demographic of the leavers.

Where violence has flared, the nature of the conflict has usually been the authorities against left of centre protest groups. Those protests have been about work, or the lack of it, austerity in one form or another, the vote, or specific issues such as Clause 28. Of course, there has been violent protest in London more than in Manchester. The 1980s Poll Tax Riots were just such an occasion. In some respects these bore a remarkable resemblance with the anti-capitalist upheavals of the noughties.

The people involved in the violence on those occasions were out for trouble right from the get-go, although again the protests might have been better policed. Youthful, often avowed anarchists, these rioters hated the whole system of governance in a capitalist democracy and were out to smash it. They don’t sound like the sort of people to ally themselves with Brexiteers who want to emphasise the British system of governance by ‘taking back control’. They were a lot younger than the average Brexiteer. It's hard to imagine pensioners from Leamington Spa turning over cars.

Indeed, the more one considers it, the prospect of civil unrest to any large degree following any remain majority in a second referendum seems improbable.

At the same time the lesson of history shows that demonstrations coalesce in big cities, many of which voted remain. So perhaps we can expect trouble in the smaller places which voted leave? Certainly there would likely be some ugly and sad examples of racism against individuals across the country, but would the residents of Boston, Lincolnshire, which had the largest vote leave majority, riot?

The likeliest outcome would be something like the vast Countryside Alliance demonstration in London in 2002 which attracted 400,000 protesters and was called to prevent interference in field sports. John Jackson, chairman of the Countryside Alliance, spoke out saying that if demands weren’t met then: "I think the countryside will erupt in fury.” Sixteen years later he’s still waiting for that to happen.

Leave voter, Ian Lamb, from Rochdale, no doubt reflects the views of many on that side of the debate.

“After any second referendum (hopefully a walk over) I am concerned there may be civil unrest in parts of the country but I would be hesitant to join in as I am not an activist per se.”

He would start his protest before the result was known. Lamb continues: “If there were to be another referendum, I would not vote and would implore all leavers to do the same. This would render the result a farce and not achieve the desired result of bringing the nation together.”

He pauses and says, “Any such vote would be the single most divisive action from the political elite that I can remember.” It’s an opinion that reflects the fury leavers would feel if the second referendum took place at all, let alone if it reversed Brexit. Yet, it doesn’t reflect a call to arms in terms of smashed windows and barricades on the streets. Dire warnings of terrible civil unrest following a remain victory seem off the mark, even scaremongering.

Indeed, the danger may come from the other direction, should the UK leave the EU with no deal, and the economy dips and there are shortages of essentials, then it's possible there may be demonstrations by those who want to stay with the EU. In that instance, some protests might be hijacked by the 'anti-capitalists' mentioned above and violence might flare. That fits more with historical precedent as it would come the from left of centre. That would fit better with the notion of upcoming civil unrest.