SURSUM CORDA. We all need a bit of that. The words are Latin and mean ‘hearts lifted’. It sums up the effect of music on a person, or, in this particular location, the feeling of a spiritual uplift safe in the knowledge of God assisted by music.

As a secularist that’s not for me.

There is nothing disposable about your work. This organ should be here for centuries

What I feel is the sense of continuity in places such as Manchester Cathedral, the collected and connected human effort combined in a will to create spaces that allow us our moment of sursum corda.

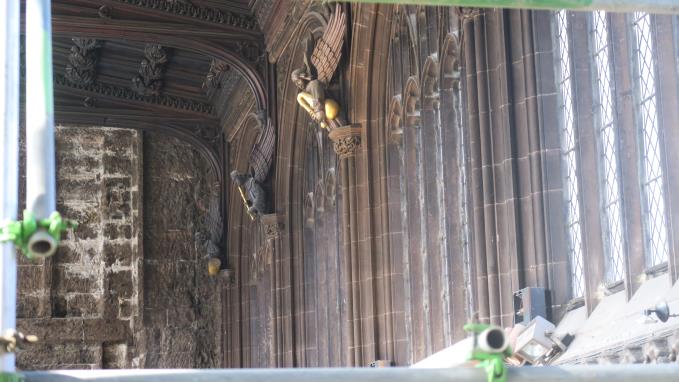

It helps when you get up high of course, as long as you don’t suffer vertigo. You can see sursum corda in front of your nose in this case.

I’d been clamboring all over the new organ in Manchester Cathedral. It’s a monster of a thing filling the whole space above the choir screen. In other words nine metres (30ft) of complex musical instrument involving over 4,800 pipes to reproduce the range of sounds any world-class organist would expect.

Looking down the instrument

Looking down the instrument Ciaroscuro of details

Ciaroscuro of detailsIt was designed and built by Kenneth Tickell & Co with pipe shades designed by artist Stephen Raw.

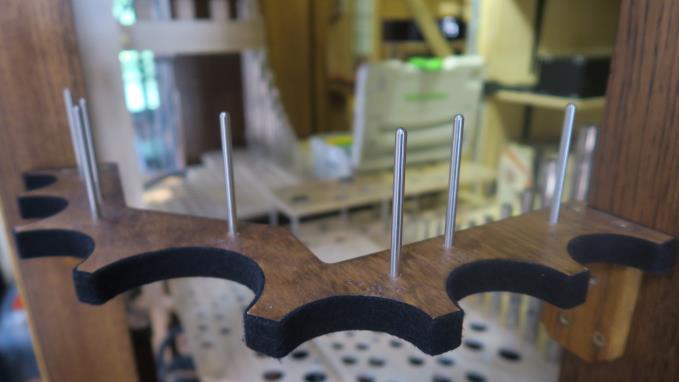

Jeff Hubbard of Kenneth Tickell & Co, who is taking me around, loses me a little with the technicalities, talking about a mechanical key action which helps the organist in the sensitivity of their playing and gives him or her better control over the pipes. I can see what he means though, when he mentions that this is the largest organ squeezed into the smallest space he’s ever worked on.

New wave anyone?

New wave anyone? The impossible complexity

The impossible complexity The impossible complexity part two

The impossible complexity part twoHubbard is a young American man who has relocated from Chicago to build and install organs.

“This instrument is not ready for public performance, it needs a lot of tuning and toning. Organists in some respects need to have four dimensional thought to get the most from the instrument. But, go on, play a few notes on the keyboard, if you want,” he says.

I play four notes. E-ton-Ri-fles. No idea why the Jam song came into my head, but no doubt Paul Weller will play the Cathedral before too long. And, in any case, it amused me.

Up close you notice the carefully crafted cut-through lettering which includes the words 'sursum corda' along with ‘Magnificat’, ‘Te Deum Laudamus’ and others. The gaps in the letters will release more sound. You also notice the gold on the pipes. This is 23.5 pure gold leaf to ensure the pipes never tarnish.

.JPG) Lovely letters

Lovely letters

Golden pipes

Golden pipesThe cost of the project is £2.5m and was funded by the Stoller Charitable Trust. This is another remarkable example of philanthrophy from Sir Norman Stoller as evidenced in our recent article about The Stoller Hall at nearby Chetham’s School of Music.

The work here is putting back that which was blown away. On Sunday 22 December 1940 during the Christmas blitz Manchester Cathedral received a direct hit from a German high-explosive bomb. The existing magnificent organ mounted on the choir screen was blown to smithereens. Sometime in 2017, 77 years after the destruction, the organ will once more form the focus for the musical life of the Cathedral.

How the old organ looked

How the old organ looked How the completed organ will look

How the completed organ will lookWe finish high in the scaffolding close to the ceiling of the nave and the choir. The views down into the body of the building are breathtaking. But also up here you get close to normally inaccessible Medieval details. The oak leaves seemed appropriate to photograph as the new organ is made from European oak. At the same time it's thrilling to be so close to Manchester's first band, the choir of angels with their wood and string instruments.

Band of Angels

Band of Angels The organ is sprouting oak again

The organ is sprouting oak againAs Jeff Hubbard continues to take me round the most impossible jigsaw every dreamt, he points out that aside from a few digital gizmos most of the elements in this 21st century instrument would be recognisable to a five hundred-year-old organ builder.

“That is part of the attraction of my job. You are following in a centuries old tradition often employing the original techniques while at the same time there is nothing disposable about your work. This organ should be here for centuries. You feel you're leaving your mark.”

On any big job there is always place for the mundane

On any big job there is always place for the mundane High craftmanship

High craftmanship The Fire Window where the German bomb fell

The Fire Window where the German bomb fell View from the ceiling into the choir

View from the ceiling into the choir  Powered by Wakelet

Powered by Wakelet