How a local photographer captured the city's growing pains in words and images

I’ve grown up with Len Grant and so has Manchester.

I became an official tour guide for the North West in 1996, and a couple of years later, I became a writer and a commentator. All of these roles had their main focus on this city.

It makes me shiver that was a generation ago.

Many people have said the book holds a mirror up to their own time in the city

Reading Len Grant’s new book Regeneration Manchester is the equivalent of flicking through a photo album of my working life - although his book stretches a little further back to 1990, covering a turbulent thirty years of Manchester’s transition.

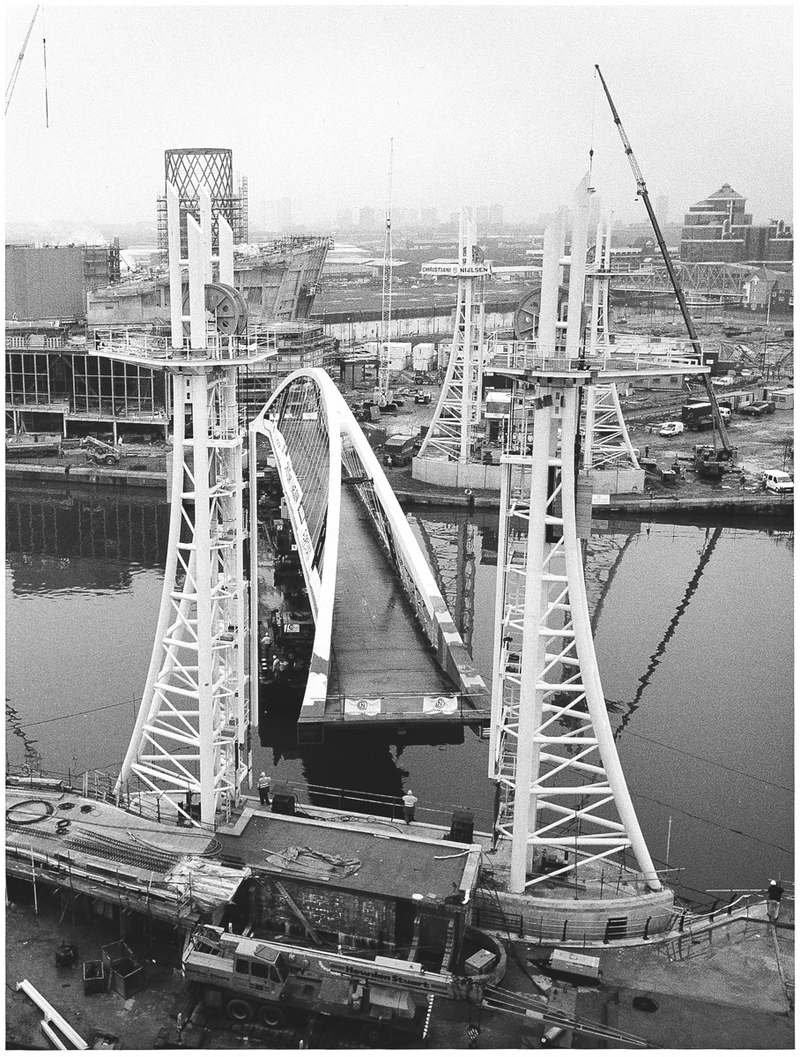

Len Grant, for those unfamiliar with him, has been the visual archivist of many of the notable projects in the city over that period. It’s all in this book: the demolition of the Hulme Crescents, the construction of the Arena and The Bridgewater Hall, the post-bomb city centre rebuild, the creation of The Lowry, Airport development, Ancoats renewal, Gorton Monastery rebirth, the arrival of The Imperial War Museum North, the New Islington renewal, the Maine Road ground demolition and much more.

Apparently I’m not alone in reacting in a visceral way to this rolodex of many of the schemes and topics I’ve explored in my own career. When I explain this to him, Grant knows what I mean. “It’s the same for many people. They have said the book holds a mirror up to their own time in the city. They’ve said how the book takes them on a journey through their own past. It certainly does that for mine.”

He pauses and then continues: “It’s a life edited really, it was hard work to get it down to 178 pages. I could have done ten different versions. So much has happened in Manchester in the last thirty years.”

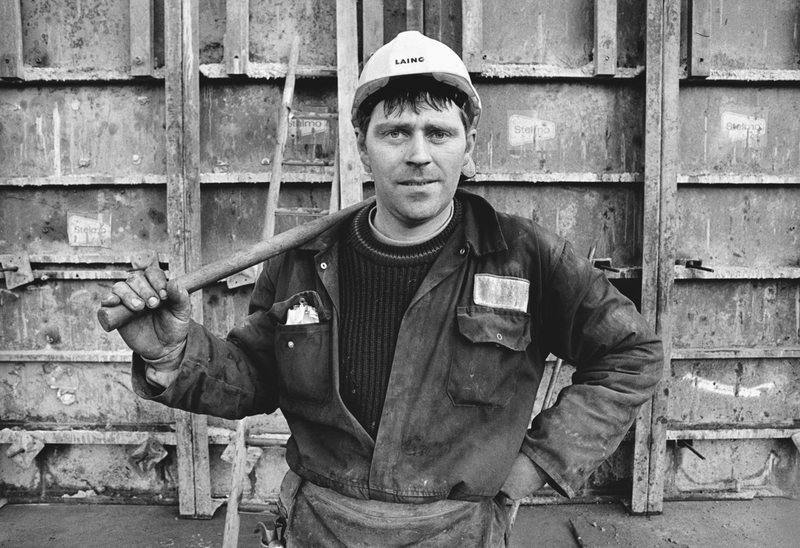

There are inevitably lots of photographs of builders and building sites. These often take on an elegiac air. I’m thinking of the one with builders lost in a web of girders during the rebuild after the 1996 IRA bomb, or the exact moment of demolition of one of the stands at Maine Road with the man on his phone in the foreground unheeding.

These have a quality of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525/30-1569): normal life, humdrum work, against a background of the grand and the epic. The first is like a detail from the construction scenes in the Tower of Babel, the second has a feel of Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, a man with a mobile phone in Grant’s image, rather than the ploughman in Breugel’s, both men going about their business careless of the big action taking place nearby.

“But it’s not only about big construction and demolition,” says Grant. “I'm proud of my social documentary work as well.”

This is key to understanding the work, the book and the man. Grant became a photographer through a passion for the lens, a classic case of an amateur becoming professional through natural enthusiasm, in this case for capturing an image.

After Nottingham Polytechnic and Business Studies he roved around a number of sales jobs before settling on a career that would become permanent. During this period he took a class where the tutor, a commercial photographer, underlined, as Grant writes, the ‘significance of making a series of images to tell a story rather than just seeking out the ‘killer’ shot.’

The social documentary images of the changes being wrought in the inner city areas are moving in Regeneration Manchester. The faces tell stories and some of the tales from society’s excluded manage to be both heart-rending and heart-warming at the same time. These are records of metamorphosis within the city just as much as those of the big schemes.

What is different with Grant is his very methodical and thoughtful approach to his work, it is never rushed and it is never careless of his subject. I wanted to use in this piece an image of a heavily pregnant lady and her fella taken, with her permission, fifteen years ago when he was cataloguing the changes within troubled east Manchester.

He had never used this image previously even though he’d produced a large format magazine called East for several years turning the spotlight on the locals rather than visiting bigwigs. But for this book the image, which is neither prurient nor intrusive, felt right. So he tracked the woman down through his contacts and gained her permission but only for the book nowhere else, so he couldn’t give me permission to use the image in this article.

If I have a criticism of the book then it is there are no value judgements placed on the way the city has developed or the architectural or design quality of the individual schemes. You literally have to read between the lines to find how Grant thinks.

Thus: ‘We may look at Ancoats or projects like The Bridgewater Hall as exemplars of Manchester’s regeneration. But for me the neighbourhood work in East Manchester is more significant. In a few short years residents who were once fearful of leaving their homes reclaimed their neighbourhoods.’

To my direct question he says, “It’s not for me to offer judgement. My career has always been doing other people’s stories and listening to other people’s opinions. Other people can make the judgements.”

I push him on this and after a pause he replies: “I think what Manchester has achieved physically is amazing, a terrific achievement. Just looks at how different the city centre is? But there are issues around community stability? Are the new high-rises creating a community, in the same way as the lower rise streets did where you leave your door and walk into a real street?”

What is also revealing about the book is how professional photography has changed. Or in many cases disappeared. When I first started writing for magazines and newspapers they all had their own full time professional photographers, now we all have our own smartphones. Yet we remain the home cooks while the real professional photographers are the chefs.

Grant is phlegmatic about this. “Back in the day not everybody had a camera in their pocket,” he says. “Professional photographers, professionally creative people, have to find a niche.” He harks back to those early photography classes. “I believe you have to tell a story, and not just that, a story people are interested in. As usual it’s all about the content, it doesn’t matter what equipment you have.”

Recently a professional in the arts for many years in this city said to me: “Manchester has changed. Where did the old Manchester go? I miss it.”

To use the old joke, nostalgia is not what it used to be. Personally I don’t miss much of it, although I regret some demolitions and the slow death of so much interesting retail (and that was before Covid-19 struck).

The big schemes in Grant’s book have proved their worth although some haven’t stood up to the test of time aesthetically. One I wish had physically stood up to the test of time was B of the Bang, the crazy and immense sculpture (56m, 183ft) to commemorate the Commonwealth Games from Tom Heatherwick. It lasted from 2005 to 2009 before it was deemed dangerous and dismantled.

Another image sums up the welcome changes in the last decade or so. The image of St Peter’s church reproduced here tells its own story. The core of Ancoats was a mess in every way. A mess with strong bones and some treasures, but it was a wasteland with hardly anybody living in it and one club, Sankey’s Soap, which lots of people were scared to leave for that early morning walk through the battered cityscape.

The picture shows the area that is now Cutting Room Square occupied by low grade industrial units. The area is an exemplar of activity and liveliness with St Peter’s, now Halle St Peters, an exemplar of re-use combined with superb new build.

There is much to celebrate from these past thirty years, but we have to make sure we bring along as much of the population as we can. That, as Grant hints, is crucial. Either way, a generation ago when I became an official tour guide and then a writer I could never have imagined the extent to which this city would develop. It's been exciting.

To purchase Regeneration Manchester by Len Grant (£25) click here.