On his 198th birthday, Jonathan Schofield takes a look at the Communism co-founder's many years in Manchester

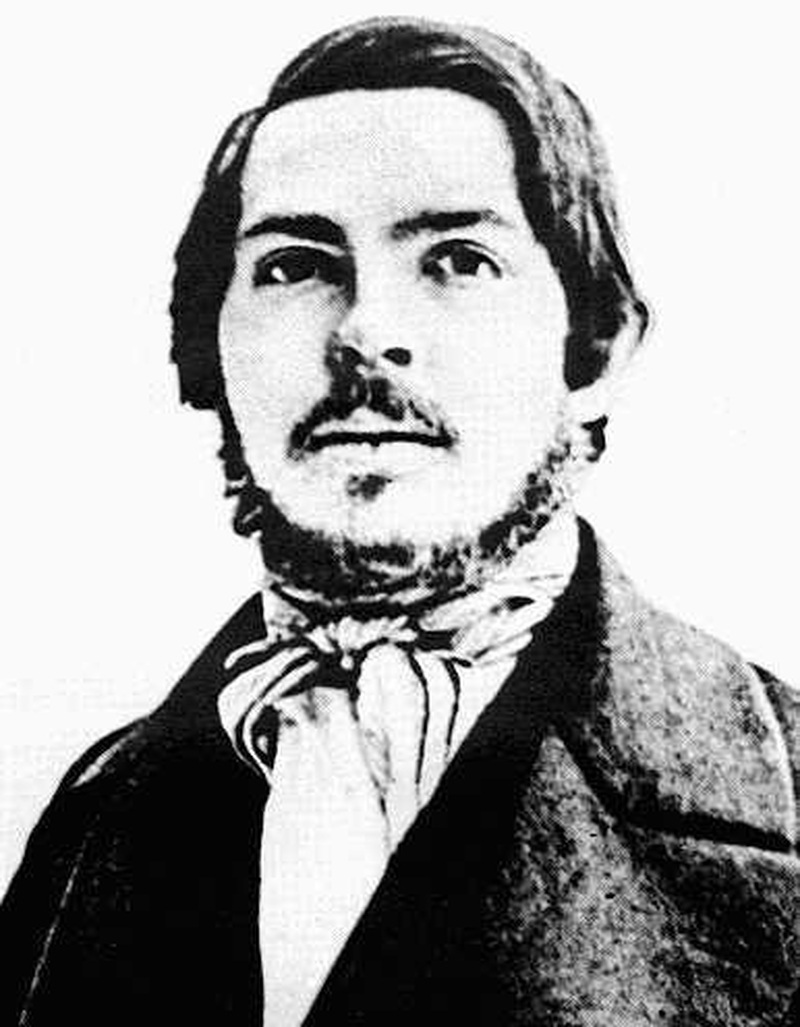

FRIEDRICH ENGELS arrived in Manchester as a feisty, curious and brilliant 22-year-old in 1842. He was in exile from his native Germany, his father having called him the ‘scabby sheep of the family’ because of his son’s progressive political views. Manchester was chosen because the family, textile manufacturers from Wuppertal in North Rhine-Westphalia, had a factory in Weaste, Eccles, jointly owned by a Dutch businessman called Ermen.

His father thought that in Manchester Engels would be removed from the corrupting influence of his fellow radicals. In truth he couldn’t have chosen a worse place on the planet for young Friedrich. Manchester summed up all the contradictions of progress and conflict in the early-industrial age. There was nowhere quite like it for a man of his leanings.

Engels would live, on and off, in Manchester for 22 years... he made his name here

As Asa Briggs wrote in his brilliant book, Victorian Cities: ‘All roads led to Manchester in the 1840s. Since it was the shock city of the age it was difficult to be neutral about it. If Engels had lived not in Manchester, his conception of ‘class’, and his theories of the role of class in history, might have been very different. In this case Marx might not have been a communist but a currency reformer. The fact Manchester was taken to be the symbol of the age in the 1840s was of central political importance in modern world history.’

Engels’ experiences led him to write The Condition of the Working Class in England, the seminal record of industrial degradation and the consequences of the unfettered free market in the mid-nineteenth century. He corresponded with Karl Marx at this time and then met him in Paris in 1844. The following year they were both back in Manchester studying at Chetham’s Library. They were writing The Communist Manifesto. Engel’s ideas and words coupled with Marx’s own observations changed the direction of communism.

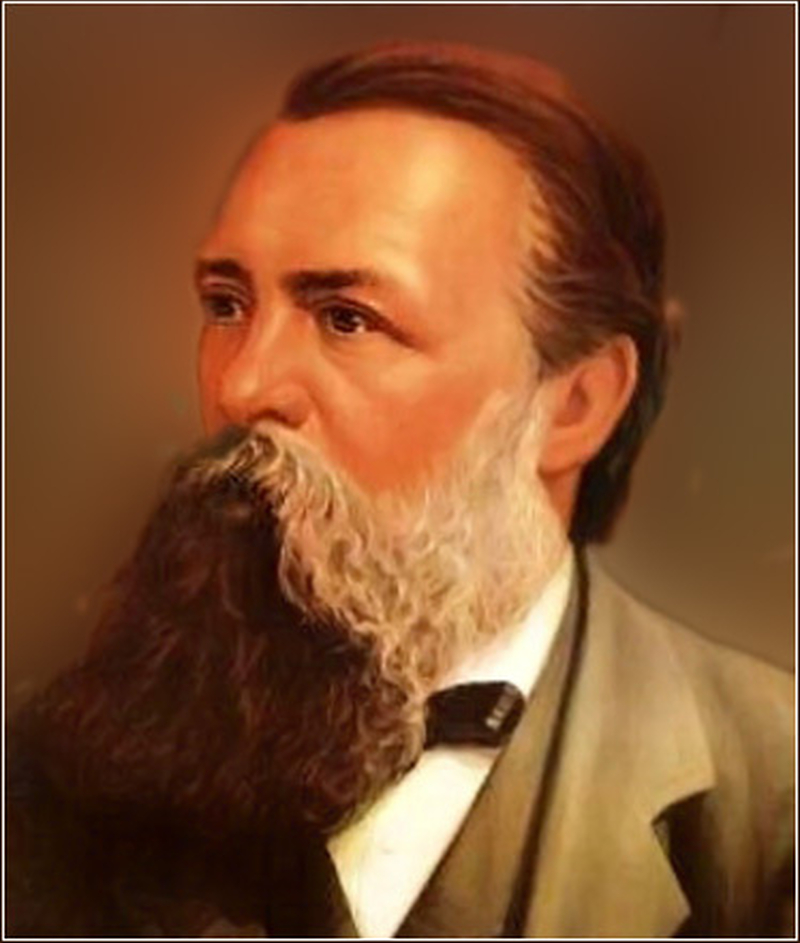

Engels would live, on and off, in Manchester for 22 years from 1842 to 1869. He made his name while here. His hero status was once so enshrined in Eastern Europe he used to have a statue in every city, albeit, usually a secondary one, next to his old mucker Karl Marx. Then the Berlin Wall fell, and shortly after the Soviet Union disintegrated, and poor old Engels was dragged from his various lofty plinths, smashed to pieces, or placed in storage. A few have survived regime change, such as the statue of the pair in Berlin’s Marx-Engels Forum. In Manchester a Soviet era statue of Engels was brought to the city in 2017 by the artist Phil Collins and placed in Tony Wilson Place next to HOME arts centre.

The best place to grab some Engels atmos is in Chetham’s Library. The desk where Engels and Marx sat and the books they read are known too, and sit on that bay window desk in facsimile form. In some respects, if only one physical memorial had to survive of the famous German’s Manchester life, then this would have always been the most poignant and finest. Chetham’s is a place of astounding charm with buildings of the 1420s and a library of the 1650s. Given Engels’ legacy is all about learning and ideas, then to have his time in Manchester marked by a library is superbly apt.

Otherwise it’s thin pickings. Physical memories of Engels’ time in Manchester are in short supply. Change has swept across the city wiping out the many houses, workplaces, pubs and clubs he used to live, work or drink within.

Stand in the perfume department of House of Fraser/Kendals (while it’s still open) close to the rear entrance to Southgate Street and you’re on the site of the Ermen & Engel’s city centre office where Engels worked for years. Communism has never smelt so good. The office work enabled Engels to send hundreds of thousands of pounds to Marx so the latter could carry on thinking and sighing in the British Library.

An extract from The Condition of the Working Class in England:

(If nothing else this shows the strength of Engel’s as a writer, but it also holds a mirror up to the sort of society we presently live within.)

‘When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains.'

One handsome image on this page shows 51-69 Cecil Street, Moss Side. The large house in the middle was rented by Engels in the 1860s for a time. This was when Moss Side was a very well-to-do suburb and one of the most prosperous in the North, close to the other plush housing areas of Victoria Park and Whalley Range.

There’s no doubting the grandeur of the terrace but its glory days are long gone in this 1973 picture. It’s hard to understand the reasons for the destruction of such fine properties by the City Council: they would be cherished now. The idea was that the city would not need such grand houses in the future and it was better to build more modest houses for a new and less wealthy population, a case of classic short-term planning.

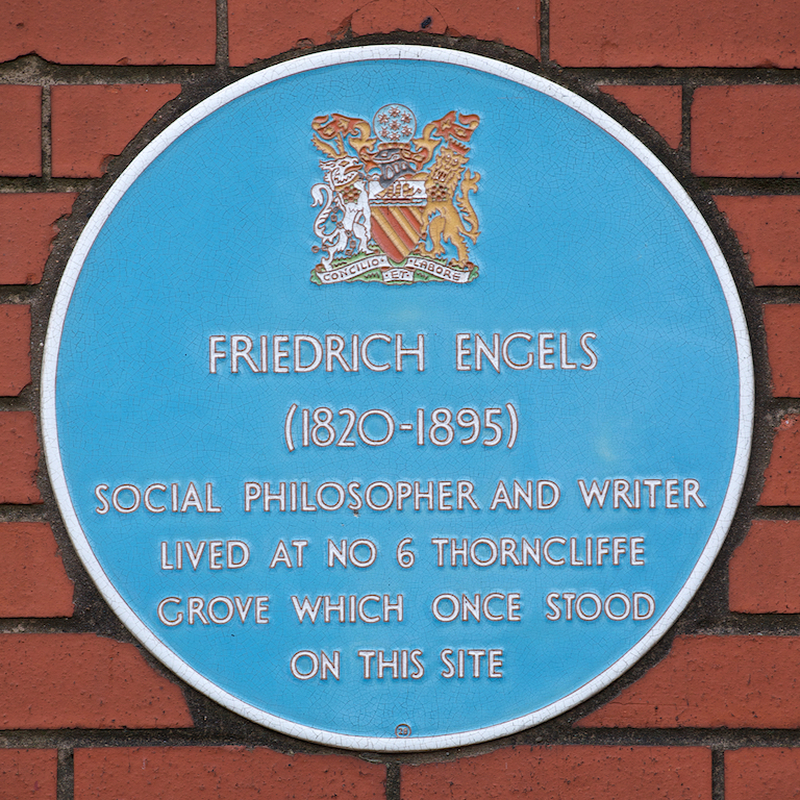

Close to Cecil Street was 6 Thorncliffe Grove, another site of one of Engel’s many houses. There is a blue plaque marking the site, which is now occupied by student accommodation. There is no trace of the nearby Albert Club and Schiller-Anstalt clubs that this eminently affable, sociable and clubbable man used to frequent, although remains of the Albert Club were excavated in 2013 prior to the construction of the National Graphene Centre. These were clubs set up by the large German ex-patriot community of the nineteenth century.

Engels lived in so many houses because he was wary of being traced by the Prussian Secret Service, but also because of the double-life he led; a respectable businessman on one side and author and communist on the other. Also the fact he lived with common law wives, Mary Burns until her death in 1863, and then Lizzie Burns until her death in 1878, meant discretion was the better part of valour for Engels. He married Lizzie on her deathbed, but by that time he’d been living in London for eight years.

Even Engel’s city centre local pub, The Thatched House, has disappeared. Demolished in 1972, Engels would meet on Saturdays in the boozer, again, with fellow Germans such as the scientists Carl Schorlemmer, Heinrich Caro and Ludwig Mond. This is where he took Karl Marx for beer during one of his many visits and also where they met British friends. The cotton factory of Engels and Ermin has disappeared at Weaste too.

The final Manchester house Engels lived in was a large and elegant house (again close to Oxford Road) by the Holy Name Church. The picture on these pages shows it shortly before demolition in 1970, no doubt it would now be the equivalent of the Engels Haus in Wuppertal and a tourist attraction - more short-term thinking from our grandparents it would appear. There’s a lovely account from Karl Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, who was staying at the house, of Engels’ last day at his job on Southgate Street.

‘I was with Engels when he reached the end of his forced labour, and I saw what he must have gone through all those years. I shall never forget the triumph with which he exclaimed: “For the last time!” as he put on his boots to go to the office. A few hours later we were standing at the gate waiting for him. We saw him coming over the little field opposite the house where he lived. He was swinging his stick in the air and singing, his face beaming. Then we set the table for a celebration and drank champagne and were happy.’

There is a block of flats named after Friedrich Engels in Eccles and Salford Uni has a climbing wall feature based on Engels’ splendid beard - which qualifies as the weirdest of commemorations. However, maybe a moment spent on the stone setts of Tonman Street (next to the Confidential office) is as good as anywhere outside Chetham’s Library to contemplate this world-famous gent and his time in the city.

Where the St John’s Gardens residences sit was the Hall of Science. When Engels arrived in 1842 he couldn’t believe his eyes. ‘At first one cannot get over one’s surprise at hearing in the Hall of Science the most ordinary workers speaking with a clear understanding on political, religious and social affairs..…I saw the Socialist hall, which holds about 3,000, crowded every Sunday,’ he wrote.

That’s 3,000 people. Can you imagine any circumstances whereby 3,000 politically engaged people would meet now in Manchester on any Sunday just to discuss politics and so forth? That Manchester played such a significant part in the creation of one of the world’s most important political ideologies, whatever we may think of communism, is worthy of recollection. What Engels would have thought of the city in 2018, it’s mighty cranes and still crushing inequalities, would be fascinating to record, although maybe painful to hear.