Jonathan Schofield examines complaints that the return of a dead German communist is a bad thing

Was Friedrich Engels resident in Manchester, on and off, for 22 years between 1842 and 1869? Was he a significant figure in world history? Did the experience of Manchester as the perfect embodiment of raw capitalism shape the ideas of Engels and his co-communist friend Karl Marx? Did those ideas have huge influence on our world and do they still carry force today?

The answer to all of these questions is yes. A big, thunderous, yes.

A well-known quote from Asa Briggs in his classic book Victorian Cities (1963) reads: ‘All roads led to Manchester in the 1840s. If Engels had lived not in Manchester but in Birmingham, his conception of ‘class’ and his theories of the role of class in history might have been very different. In this case Marx might not have been a communist but a currency reformer. The fact that Manchester was taken to be the symbol of the age in the 1840s.. was of central political importance in modern world history.’

Case closed then. It was entirely justified for artist Phil Collins, as part of Manchester International Festival 2017, to retrieve an Engels’ statue from dereliction and abandonment in Ukraine and bring it to the city. Thus the arrival of this outside HOME in First Street, Manchester is good in terms of education, story-telling, context and tourism? Win-win.

Well, no. Some people aren’t happy at all, especially those on the left, which may seem surprising given Engels was one of the big daddies of Communism. To some the statue marks the Disneyfication of Marx and Engels.

Michael Herbert, creator of website Radical Manchester, an academic and leader of Red Flag Walks, despises the statue’s arrival to such an extent he’s not going to include it in any of his tours or talks. He’s not alone in this.

“The whole project reeks of tourism and heritage, not politics and history,” says Herbert. “The statue has also been put up on private land where if you tried to give away copies of The Communist Manifesto you would be stopped.

“As young men in the 1840s Marx and Engels believed capitalism was a dynamic force, sweeping aside the musty, archaic social and economic infrastructure of feudalism, but one that would in turn be superceded by the working class once it organised itself and put its own interests first.

“I think the Engels statue is a fundamentally flawed notion, being static and immobile, the very opposite of what their ideas were about (and it is the ideas that are important).

“If people really want to remember Engels,” continues Herbert, “get active, join a Union and fight low pay and zero hours; or join a campaign against austerity and benefit cuts.”

Herbert finishes with: “Unfortunately (the statue) seems to be the first in line of similar pointless projects with Mrs Pankhurst and Peterloo to follow.”

This seems curious reasoning. Some understanding of history, or rather, how we have got to where we are now, locally and regionally, helps build identity and a sense of place. It also helps us make informed decisions on politics and how we wish to direct our lives.

Of course we are all shaped by personal prejudice arising from our upbringing and cultural background, but one thing I have learnt as a tour guide and writer on the city’s history for 21 years is that physical reference points are vital in illustrating the story of Manchester. Seeing is believing.

The physical reference points of Engels’ 22 years in Manchester have largely vanished. The only significant place that remains is the beguiling and enchanting Chetham’s Library, where people can sit at the table where Marx and Engels’ sat while the German pair were writing The Communist Manifesto. Visitors can even read the books the famous guests studied.

Now we have a statue. Suddenly the story of Engels’ time in Manchester, and the wider context of his global influence, is easier to illustrate and brought into sharper focus. That the statue is only a stone’s throw from Little Ireland, a horrific area of Manchester which Engels wrote about in his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England, is all the better.

For a city to really be itself it has to be aware of its history, good and bad...

Phil Collins, the artist who brought the statue to Manchester, says: “In the city centre we need more markers of these incredible radical histories. The statue underlines this and also Engels’ relationship with Manchester. I think it creates a dialogue for modern day tensions within the city. It could be a focus for discussion over the relationship between private and public space, about the growth across the central areas of luxury flats rather than social housing.

“The statue might make people question the way cities develop today. After all, close by there’s a Pizza Express and a Starbucks already in place, with Gazprom also moving in soon. I see it playing a role in education for schools and universities and the discussion of all sorts of ideas.”

Collins pauses.

“Remember,” he continues, “Engels was a complicated person who didn’t live outside the system, he was a businessman, he liked Champagne, he was a member of clubs in the city. I think the location reflects this and again is a basis for debate.”

There is a lovely scene described by Karl Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, who was staying with Engels in Manchester when he left his day-to-day job in the family business in 1869.

‘I was with Engels when he reached the end of his forced labour. I shall never forget the triumph with which he exclaimed: “For the last time!” as he put on his boots to go to the office. A few hours later we were standing at the gate waiting for him. We saw him coming over the little field opposite the house where he lived. He was swinging his stick in the air and singing, his face beaming. Then we set the table for a celebration and drank Champagne and were happy.’

Nothing is simplistic in history.

Another criticism, this time from Manchester’s Ukrainian community, revolves around the lack of consultation over bringing a Soviet-era slab of propaganda into Manchester. After all, this Engels’ statue was created to reinforce Soviet control and Soviet ‘communism’ in Ukraine.

As Kevin Bolton wrote in The Guardian: ‘Communism was a very real thing for British Ukrainians from the 1950s to 1990s. Many had relatives on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. Others had lost family in the Holodomor famine (a man-made Soviet famine that killed millions of Ukrainians). Anti-Soviet protests in Manchester or London were a common part of diaspora life. You could argue they are also part of the 'Manchester Radical' narrative. The aftermath of the Soviet era still impacts Ukraine and its diaspora today.’

Bolton’s most powerful point, and one which will haunt this statue, is: ‘Would we tolerate the presence of Nazi propaganda in Manchester?’ The statue at HOME bears witness to the feelings in Ukraine when the Soviet Union fell and the country became independent. The lower part of the statue carries traces of blue and yellow paint, the colours on the national flag. Of course, presently, Russia is the de facto occupier of large parts of the country.

Back to Engels and we should remember he nowhere condones mass murder, torture, show trials. In this respect the statue can also be read as a warning. The Soviet Union twisted communism into a tyranny Marx and Engels’ didn’t anticipate. To use an old aphorism, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

What is clear is that people will interpret Friedrich Engels’ reappearance in Manchester as they see fit. As a guide and writer in Manchester I will use it carefully in full knowledge of which regime created the image. Nonetheless I am pleased it is here. For a city to really be itself it has to be aware of its history, good and bad. It has to teach its story to its citizens and tell its story to its guests, and if that comes with a degree of myth-making, so be it. To me the return of Engels’ adds context to Manchester and to reject it misses the point. This was a man whose experience of Manchester affected world history. This is a big statue with big shoulders.

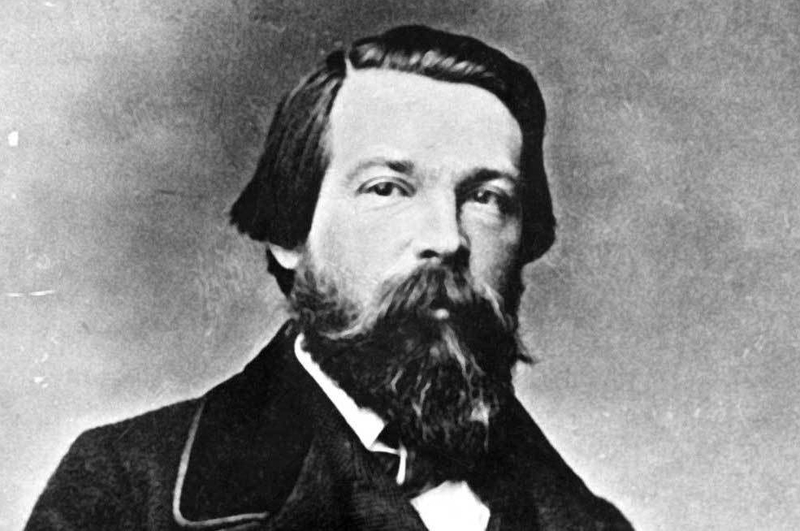

Who was Friedrich Engels?

Friedrich Engels, a German, lived for almost 22 years in Manchester between 1842 and 1870. He came as an agent for a textile company in which his father had a partnership. Although he loathed the job it allowed him to examine how Manchester had developed. It came to represent for him the perfect capitalist city with all the contradictions and problems that entailed.

Touring the city with common-law wife Mary Burns, a working class girl with access to the roughest areas, he compiled material for his famous work The Condition of the Working Class in England. This influenced all subsequent thought on industrialisation, in particular the work of Engels’ close friend Karl Marx. The following is an extract: ‘Society in England daily and hourly commits what the working-men's organs, with perfect correctness, characterise as social murder, it has placed the workers under conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; and so hurries them to the grave’.

Marx would visit Engels for weeks on end. In Chetham’s Library there’s a record of their visit in 1845. It’s thought they wrote part of The Communist Manifesto in the city. However Engels was not just a social reformer in a sober suit, in character he was warm and approachable. He loved sport, and used to attend a fox hunt in nearby Cheshire and was a prolific pub-goer and club member.