Jonathan Schofield looks into how whole streets and beautiful houses have been wiped away

I was looking for Friedrich Engels recently - despite the fact he's been dead for 124 years. You go looking for one thing and you find another. I was looking for some of the places this father of Communism had lived, worked and played in during his 22 years in Manchester.

They were all gone, except one. It has been difficult to understand this wholescale destruction. Many were fine properties that would be cherished now.

The idea was it was better to build more modest houses for a new less wealthy population

The main image above shows 51-69 Cecil Street, Moss Side. The large house in the middle was rented by Engels in the 1860s for a time. This was when Moss Side was a very well-to-do suburb and one of the most prosperous in the North, close to the other plush housing areas of Victoria Park and Whalley Range.

The image below shows what Cecil Street looks like now. The council in a ridiculous moment of 'big planning' demolished these buildings and thousands of others, thinning the population density at the same. Tens of thousands of people were 'slum-cleared' out to estates beyond the city boundaries or on its fringe.

'A new future has to be created for these areas which have outlived their function,' a council report read. The feeling was that the glory days of the nineteenth century, when the well-to-do had lived in these grand terraces, were gone forever. Driven by a kind of post-World War II self-hatred, the city of the first modern industrial society, scarred by the energy of those years, looked in the mirror and reeled back in horror. Better to wipe all that away, get rid of the old stuff, with its dodgy politics and Imperialism. Make a fresh start.

Thus Cecil Street was torn down. The middling folk and the rich in the coming car age, it was thought, would all be living a commute out of the city. Why would they ever want to live in areas close to the city centre or even in the city centre? So it was better to get rid of all old aspirational stuff and provide modest little houses for a city which would never attract that sort of investment again. It was idiotic short-termism.

This was at once short-sighted, without reference to history which usually reveals how the wheel turns again. It was also condescending, indicating people in future in these areas would be incapable of occupying grand and gorgeous properties, so it was better to build more modest houses for a new less wealthy population.

Rowland Nicholas, the architect of the 1945 Manchester Plan, seemed to suggest something else too. ‘Many of our present difficulties are complicated by the fact that in the last century buildings were designed to last too long; they have remained structurally sound long after they have been rendered obsolete by changes of function and progress in building technique’. What? So is Nicholas implying that new building techniques were superior because they didn’t result in buildings that truculently refused to fall down?

The lesson for current planners and developers is plain. Do not destroy beautiful and interesting buildings because we cannot be certain what the future might bring and how areas might change and develop. Who would have thought for instance that the lawyers and doctors practices on St John Street would return to housing, as they are now and as our article here revealed.

Back to the pursuit of Friedrich Engels who lived in Manchester, on and off, from 1842 to 1869 and made his name while here. His hero status was once so enshrined in Eastern Europe he used to have a statue in every city, albeit usually a secondary one to his old mucker Karl Marx. Then the Berlin Wall fell and, shortly after the Soviet Union disintegrated, poor old Engels was dragged from his various lofty plinths, smashed to pieces or placed in storage. A few have survived regime change, such as the statue of the commie pair in Berlin’s Marx-Engels Forum. Now, of course, we have shipped one over and he stands outside HOME arts centre, arriving here as part of Manchester International Festival 2017.

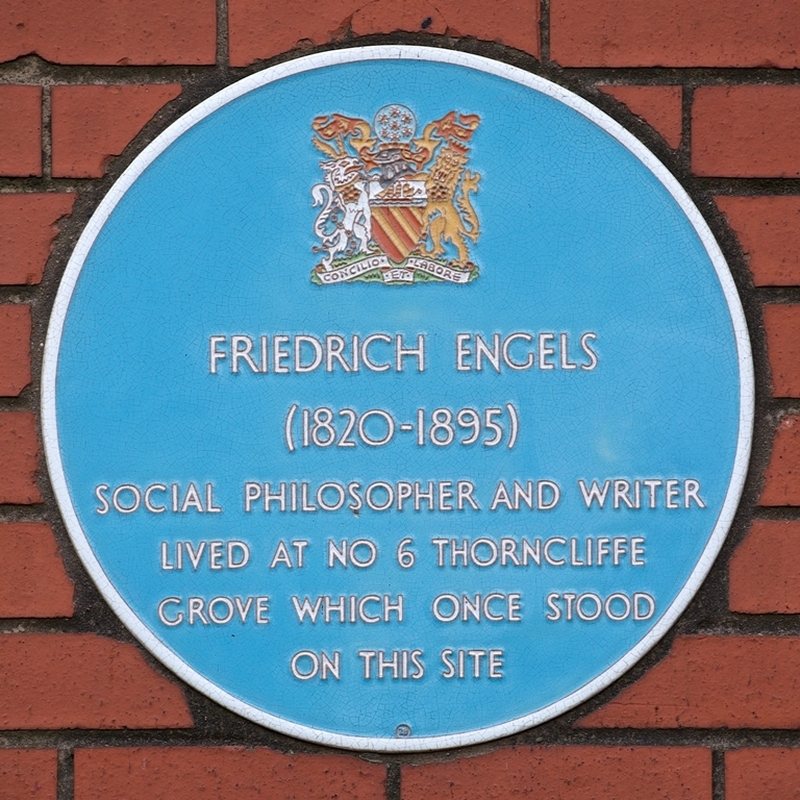

Close to the demolished properties in Cecil Street was 6 Thorncliffe Grove, another site of one of Engels' many houses. There is a blue plaque marking the site which is now occupied by student accommodation. There is no trace of the nearby Albert Club and Schiller-Anstalt club, this eminently sociable and clubbable man used to frequent either, although remains of the Albert Club were excavated in 2013 prior to the construction of the National Graphene Institute. These were clubs set up by the large German ex-patriot community of the nineteenth century.

Engels lived in so many houses because he was wary of being traced by the Prussian Secret Service and also because of the double-life he led of being a respectable businessman on one side and author and communist on the other. Also the fact he live with common law wives; Mary Burns until her death in 1863, and then Lizzie Burns until her death in 1878, meant discretion was the better part of valour for Engels. (He married Lizzie on her deathbed but by that time he’d been living in London for eight years.)

Even Engels' city centre local pub, The Thatched House, has disappeared; demolished in 1972. Engels would meet on Saturdays in the boozer often, again with fellow Germans such as the scientists Carl Schorlemmer, Heinrich Caro and Ludwig Mond. This is where he took Karl Marx for beer when Marx was on one of his many visits and also where they met British friends. The office where Engels worked on Southgate Street was demolished for Kendals department store (now House of Fraser). The cotton factory of Engels and Ermin has disappeared at Weaste too. Engels worked in his father’s Manchester business to provide an income for himself but also, partly, for Marx.

We are fortunate in one respect. We do know that Engels and Marx studied in 1844 at Chetham’s Library. The desk where they sat and the books they read are known too. In some respects, if only one physical memorial had to survive then this would have always been the finest. Chetham’s is a place of astounding charm, buildings of the 1420s and a library of the 1650s, and given Engels’ legacy is all about learning and ideas then to have his time in Manchester marked by a library is superbly apt.

The final house Engels lived in was a large and elegant house again close to Oxford Road. The picture on these pages shows it shortly before demolition in 1970. Yes, that was another fine place that would no doubt start to become viable as a family home once more.

There’s a lovely account from Karl Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, who was staying at the house, of Engels last day at his job on Southgate Street. ‘I was with Engels when he reached the end of his forced labour, and I saw what he must have gone through all those years. I shall never forget the triumph with which he exclaimed: “For the last time!” as he put on his boots to go to the office. A few hours later we were standing at the gate waiting for him. We saw him coming over the little field opposite the house where he lived. He was swinging his stick in the air and singing, his face beaming. Then we set the table for a celebration and drank Champagne and were happy.’

The Champagne socialist planners of the fifties and sixties seemed almost determined to eradicate all trace of Engels. This wasn't the case of course, they weren't being particular, they were just as careless with much of Manchester's history and legacy. In his late sixties architectural series featuring Manchester, he directly criticises the city for not looking after its historic buildings.

It was as though the city council thought all that stuff was for Chester and York and their ilk, not for a city such as Manchester. What Manchester was looking for is stated in the 1945 Manchester Plan, and that's a clean break to produce a 'noble, braver age in which the human race will be the master of its race'. We don't get that type of language in 'spatial framework documents' anymore. Let's hope we don't lose anymore Cecil Streets either. Where there are any left.