MANCHESTER's past is being revealed following the Palatine Building's demolition on Victoria Street.

The big question is who dug this ditch and when?

The ancient geography of the site of the post-Roman settlement from which all else spreads in Manchester is becoming clear. This settlement took place at the confluence of the River Irwell and River Irk where the rivers had cut through the land to form, on the south east side, a high craggy promontory which was a naturally defensive area for incoming peoples.

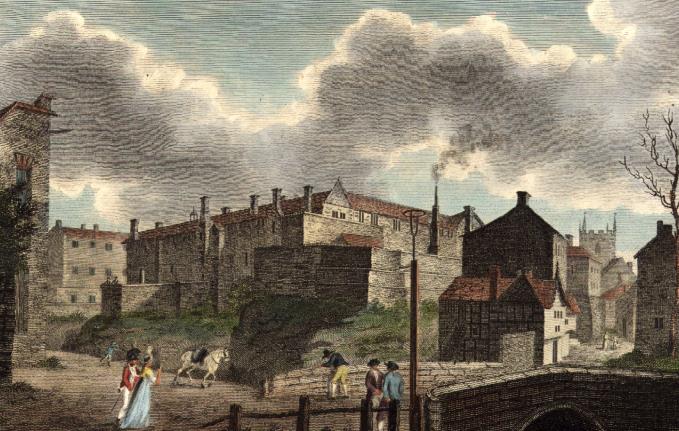

This original site can be glimpsed on prints from the eighteenth century onwards before later developments masked the site.

The site in 1797

The site in 1797The most interesting feature, coming into sight for Mancunians, is a shallow and roughly arched hole in a tall wall. Above lies the medieval building of Chetham's Library and Music School from 1421. This arch has been built over an earlier ditch, now filled, and is 5m (17ft) beneath the level of Chetham's courtyard. The ditch was cut through the solid red sandstone of Manchester. It is, according to an archeological report from 1983, 6m (20ft) wide.

The revealed arch and filled-in ditch

The revealed arch and filled-in ditchThe great depth and width of the ditch under the arch has given rise to the suggestion that it follows a natural gulley running towards the River Irwell which was widened to create a defensive feature. This ditch still lies many metres above the confluence of the rivers. If the average height of a double-decker bus is 4.38m (15ft) then the vehicle in the picture below gives us a measurement of around 10m (32ft) above the river for the present road level. Therefore, the combined height from rivers through to ditch to the ground level of Chetham's courtyard is 15m (50ft). This is a considerable height to scale for any river bourne aggressor.

View from the Salford side, showing the confluence of the smaller and now culverted River Irk (under the arch on the left) with the main River Irwell in the foreground. The medieval building of Chetham's lies above and right of the bus, 15m (50ft) above the water.

View from the Salford side, showing the confluence of the smaller and now culverted River Irk (under the arch on the left) with the main River Irwell in the foreground. The medieval building of Chetham's lies above and right of the bus, 15m (50ft) above the water.  The ditch emerges with the low arch to the left of the digger

The ditch emerges with the low arch to the left of the diggerEvidence over the last couple of hundred years suggests our ditch climbed the cliff to the present Chetham's courtyard and then curved round to the River Irk to the north. The ditch cut across the present courtyard in front of the modern-day garden and the first row of car park bays, splitting the yard, playground and car park of the present Music School.

This would possibly account for the elongated nature of the medieval buildings stretched out behind the substantial sandstone ditch and jammed fast against the low cliffs above the River Irk. It's odd in a grand medieval building of the 1420s for instance to place the kitchen anywhere other than directly behind the main hall. Here it is to one side as though it were made to fit in the space available.

View from Manchester Cathedral tower, a month or so ago before the arch and ditch were revealed, showing Chetham's medieval buildings.

View from Manchester Cathedral tower, a month or so ago before the arch and ditch were revealed, showing Chetham's medieval buildings. Chetham's was built originally as a college for priests for the expanded parish church, known then as a Colliegiate Church. This is now Manchester Cathedral. It changed character after the Reformation in the 1540s and then again after the English Civil War, when in the 1650s, Humphrey Chetham, through his will, created the library and a school. The buildings have been described as the finest of their date and type anywhere in the United Kingdom and can be toured (click here). Before these buildings there had been a manor house and small, very small, castle on the site.

The big question is who dug this ditch and when? It had been sealed, rather elegantly, as the pictures on this page shows, with boulders and cobbles. Previous investigations have found late medieval pottery and even the odd leather shoe of the same date, within the in-fill, so the ditch must predate that.

Another view of the arch

Another view of the archIt was thought in the nineteenth century that the ditch was Iron Age, in otherwords from before the Romans arrived in area in 79AD and built a fort almost a mile south in present day Castlefield. This is considered these days as too old, and a much more likely date is sometime in the Anglo-Saxon period. This is still conjecture and further archaeology is needed.

Assigning ethnicity to early settlement is fraught with difficulty, but the etymology of the name points at the Anglo-Saxons. Later ditches further out into Manchester, such as the artificially widened watercourse at Hanging Ditch, follow from the one revealed under Chetham's, as the settled area expanded. You can see Hanging Ditch and its subsequent medieval bridges under the fine teashop, Propertea, close to the cathedral.

So our ditch is, you could say, Manchester's first ditch attempt.

It's tempting to allow flights of fancy to carry away the imagination at this point. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers, dubiously it must be said, to Edward the Elder, the first king to unify Britain, rebuilding Manchester in 920 after it had been destroyed by the Danes, aka those dreadful Vikings. If that is the case it seems our ditch saw some action and failed.

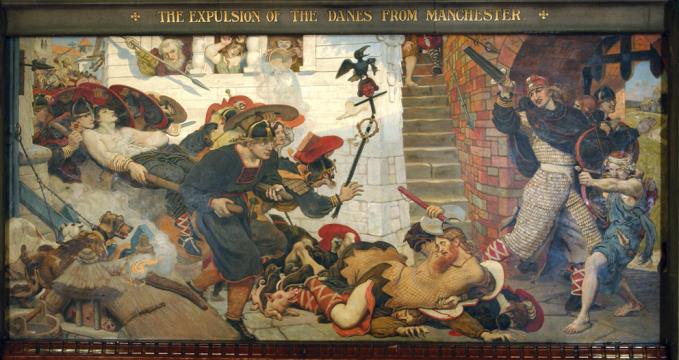

Ford Madox Brown dreams of the past

Ford Madox Brown dreams of the pastFord Madox Brown in 1881 completed his mural for Manchester Town Hall entitled, 'The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester'. He described what he'd painted:

'A rich and successful young chieftain, the wearer of many bracelets, but now badly wounded, is being borne past on a hastily constructed stretcher, his companions endeavouring to protect him and themselves with their uplifted shields as they run the gauntlet of the townsfolks' missiles. In front of these four men have fallen confusedly, one over another, on the ground. The pavement consists of the polygonal blocks that the Romans had formed their road of which ran through Manchester.

'From a house which faces this scene a young woman has thrown a tile that strikes down the "Raven" standard-bearer. An aged inmate from the same window throws a spear, the national Saxon weapon, while two little boys gleefully empty a small tub of boiling water on the fugitives.

'The Danes, who in a group have reached the shelter of the rampart gate, pause for one moment to hurl back threats of future revenge on the inimical townspeople, whose chained-up dogs bark fiercely at the runaways, while in the background the soldiers of Edward the Elder are seen smiting the unfortunate loiterers in the race for life.'

Of course Manchester has never looked anything like the painting, but let's not be churlish, especially as Brown came up with a decent joke. He brought the pig in the picture into the Town Hall to paint and it went walkabout. He was forced to apologise by letter calling the situation a 'pigmentary situation'.

So what is going to happen to Manchester's first ditch attempt site? It's currently being levelled, protected under top soil, to allow future archeological investigation. The ditch and arch will remain visible. The area will be landscaped as part of the 'Medieval Quarter Masterplan' as we described here.

If you go down to take a look, a good viewing point to get the context of the site, is over the river, looking through the lattice ironwork of the bridge on the Salford side (the viewpoint shown in the fourth picture on this story, the one with the double-decker bus). Look out for my mate, Mr Humphrey Heron. He's there hunting every morning. He stands on the pier of the railway viaduct at the confluence of the rivers: he and his ancestors the one constant, besides the rivers themselves, of a time stretching way back beyond the creation of our venerable ditch and arch. Give him a wave, he likes it.

The constant visitor

The constant visitor