An unusual outing with Japanese artists forces Jonathan Schofield to ponder the state of the city

I was asked to take some Japanese artists around the city last week. They defined politeness. They were all in their twenties, yet their courtesy and patience was astonishing, while as well-known artists they were incredibly unpretentious and unaffected. My guests were eager to learn all they could about the city and took endless notes. They videoed everything.

They had one stipulation. They didn’t want to see the traditional sights, no Royal Exchange or John Rylands Library, instead they were after the scruffy city centre hinterlands. They had been commissioned to deliver an art project for Manchester and for their purposes the word ‘gentrification’ was an expletive. The problem is the city centre is running out of rough and ready zones as the apartment wave keeps rolling outwards.

Men stand outside the shops here, with shutters down over the windows

So there was only one place to go. It had to be that litter-strewn, anti-aesthetic, warehouse-crazy land around Strangeways Prison. That’s where we chose for a Tuesday perambulation. We strode a loop from Angel Meadow, up to Cheetham Hill and then along Derby Street, before dipping down to Bury New Road, via the entrance of Strangeways. Then it was over Bury New Road to a footbridge across the River Irwell that leads to Trinity Way and back into the city centre.

I like strolling these areas. You get an alternative view of Manchester. They are the antithesis of touristy. These areas show, as TS Eliot wrote in Whispers of Immortality, ‘the skull beneath the skin’. You have to seek them out though, get out of the car. Not that most people want to do this, instead they want ‘nice’ places where there is little litter and the buildings look like they are cared for, rather than simply providing a roof for sales of knock-down wholesale.

The traders in Cheetham Hill and around Bury New Road are largely of Asian and Middle-Eastern origin. Before these traders arrived there was a Jewish community here, hence the Jewish Museum on the main road. In Derby Street an Asian wholesaler sits inside a former Jewish School from 1869. This was built by the established Sephardic community (originally from around the Mediterranean basin) who wanted to teach the incoming Ashkenazi folk, poorer Jewish immigrants, how to be more British. Yiddish wasn’t allowed.

Across the road is the former headquarters of Marks and Spencer from 1901-1923, also a clothing wholesaler. The working class Ashkenazi came to Britain to make a living and find opportunity in a safe and stable place and that’s what many of the recent immigrants have done. It’s the way history in cities flows.

My Japanese guests were fascinated by this movement of peoples. Remember, Japan has a poor record in allowing immigration for such a developed nation. Less than 2% of the population is immigrant and this includes ethnic Japanese from the Americas. In the UK the ‘foreign-born’ population was around 12% at the 2011 census.

The present businesses are usually law abiding and legal despite being seemingly unconcerned by litter issues. Down around Bury New Road it’s different. This has been dubbed the ‘counterfeit capital of Britain’. In December 2017, police seized three shipping containers of counterfeit goods in one raid alone.

Men stand outside the shops here, with shutters down over the windows. The men invite people in to see if they can be tempted to make a purchase; they invited the Japanese group in. The shutters are down to stop the prying eyes of the police and the immigration officials. Should word get out that the authorities are prying, those doors are locked double-quick and the store is closed. Any customers left inside have to wait until the all-clear is given. It’s so blatant it’s almost comical, although there’s nothing funny about the criminality these shops fund in trafficking and drugs.

The contrast between this Manchester and the city centre became stark as our group headed back via a sweatshop on one side and that bona fide purveyor of luxury menswear, Private White VC, on the other. Then, as we crossed over the River Irwell, the cranes and towers of the city centre loomed close. Another two minutes and we’d be able to see the building where Man City's £15m-a-year manager, Pep Guardiola, lives.

Before that, on the western side of Trinity Way, we passed the cool, modern architecture of Urban Splash’s Irwell Riverside development, which seemed miles distant from the grim, black-shuttered shops and the day-to-day existence of the people just four minutes away. The contrast is so sharp, it almost induces a snort...of what? Amusement, derision, despair, anger, hope? All of them together, perhaps. There have always been such cheek-by-jowl differences in our cities and particularly in Manchester.

The problem now is that the statistics show us the chasm between have and have-nots has grown much wider since the economic crisis ten years ago. The TUC are meeting in Manchester this week and a GMB Union report has found that the value of average earnings between 2007 and 2017 in real terms has declined by 10.4%, when inflation of 31.7% is taken into account, and it’s those at the bottom who have been hardest hit. It must be said that this survey was carried out in the London region, but that does make you wonder if it might not be far worse away from the capital’s bubble economy.

A problem is that, for many years now, but particularly with the Brexit obsession/distraction, the government seems to have no thought for what is happening in the country at large. I mentioned the ‘nice’ places earlier, but they are becoming increasingly rare in the UK, as high streets collapse under the force of the internet, cash to look after roads and the public realm declines, and as the police become an almost mythical law enforcer.

Homelessness in the big cities is a disgrace, as we know all too well in Manchester. The contempt for law and, indeed, decency of many city centre beggars beggars belief, so to speak. Why hasn’t this been sorted? We wring our hands, yet still so many of us give them money.

The Conservatives always declared themselves to be the party of law and order, but they are becoming a government of lawlessness and disorder, as they rip each other apart over whether Boris Johnson is actually a future leader or a clown. While the governing party bickers much of the nation suffers from the continuing blight of austerity. Yet, in a way, perhaps our cities have become more honest. Or at least come full circle.

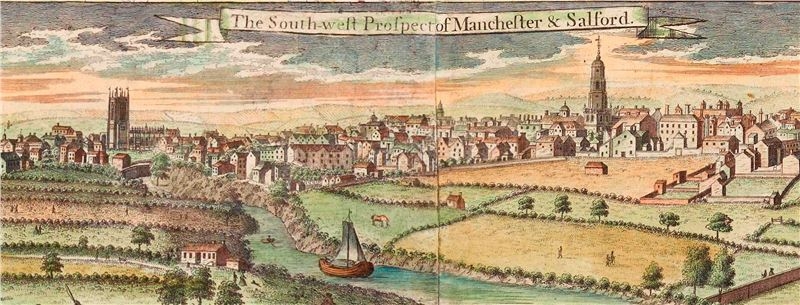

I look at the 1750 map and diorama of Manchester by John Berry and it provides images of a town just a few decades before steam-powered industry changed everything. This is a town you could walk across in fifteen minutes from farm fields to farm fields. There are narrow streets of houses, where conditions must have been utterly miserable, yet right amongst them are vast mansions, almost palaces, of families grown and growing extraordinarily rich. It seems that juxtaposition has returned with a vengeance and has grown obvious once more. Our cities have become more honest about their true nature.

As we approached Blackfriars Street I asked if my Japanese guests had plenty of material to work with for their artwork. They said more than enough. Of course they had. They were amazed by all they had seen, by the way the jigsaw of Manchester fitted together.

Yet I can’t help thinking about those ultra-polite Japanese visitors. They thought the Brits they had met were ultra-polite as well, you know, doing our thing of saying sorry when we didn’t need to. Sometimes it occurs to me that our society in this United Kingdom has the character of an alcoholic; gracious, lovely and amusing when sober, but potentially rude, ugly and angry when drunk or deprived of drink.

Taking overseas guests around gives you perspective on your city. This article might seem pessimistic, yet there is so much life on these streets, so many different peoples, so many different ways to just get by or to prosper. I live two and half miles from Manchester Town Hall and I wouldn’t live anywhere else in the world. The problem is that right now, in 2018, it’s hard not to be concerned about the evident decline of public services and the retreating police. That skull beneath the skin is beginning to show through. Just take a walk through the streets in the shadow of Strangeways.