Being from a mixed Chinese and English background, I have found that food has always been my anchor to an otherwise distant and often abstract heritage. Admittedly, I’ve had the best of both worlds and have only ever been exposed to ‘proper’ Chinese food. However, like many others out there, I have on occasion been the unfortunate victim of the dreaded ‘Two Menus’.

The future of Chinese restaurants depends on their ability to move forward and respond to the demand of modern diners, this includes committing to providing the same experience for everybody

For those who are unaware of this phenomenon, allow me to explain, the majority of Chinese restaurants in Manchester have two separate menus, one for the Chinese and one for everybody else.

The latter features all of the Anglicised dishes that have come to form the impression of what many people constitute as Chinese food, when in actual fact these dishes were developed to gently introduce Western taste buds to Eastern cooking.

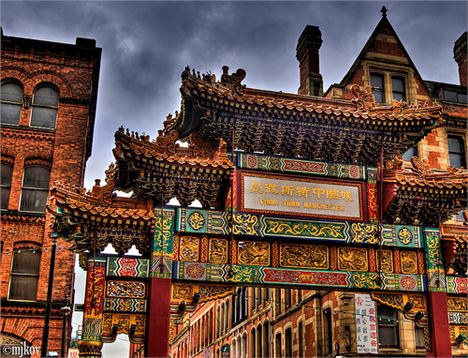

China town - dark clouds of change

But surely, in the year 2013, when everybody is more food and drink savvy than ever, can we not expect more from Chinese restaurants? Why are they not rising to the occasion to provide ever more adventurous customers with something worth talking about?

Good, authentic cooking should be exciting, not comfortably uninspiring. Chinese cuisine is one of the most diverse and intriguing cooking styles in the world and yet many diners are, through no fault of their own, so limited in their experience.

Let me conceptualise this a little by depicting the contrast between the experiences of a non-Chinese family and a Chinese family in a restaurant.

A couple of years ago, I went into my second favourite Chinese in town (no kiss-and-tell) with my non-Chinese mother and grandmother, all of us well informed in the cuisine and etiquette. Everything was going so well until the forks and the menus arrived. Presumably due to my non-Chinese company, I was given the Anglicised menu which lists only a small fraction of the dishes that I have come to know and love.

What, no forks?

This means that I have to go through the motions of confusing the waiter as I parrot the names of my favourite dishes in Chinese. He then proceeds to speak back in lightning fast Cantonese, forcing me to reply that “I’m sorry, I don’t speak Chinese” and a very awkward silence follows. The evening continued to plummet when I asked for the bill and I saw that we had been charged for the tea.

These occurrences may sound like minor, trivial flaws to the overall evening but in reality they represent a much wider injustice and inequality that exists in the industry.

To demonstrate, let me continue by giving a brief description of the standard experience when dining with the Chinese side of my family instead.

Firstly, no forks. If in 2013 somebody can’t or is unwilling to try and use chopsticks properly, let them ask for their own forks; I consider it rather patronising when forks are immediately dropped on the table. Then the authentic menus arrive, featuring a myriad of options including various Chinese cooking styles. All of the following are complimentary: pots of jasmine or black tea (or both, and as many as you like), soup for the table as an appetiser, followed by sweet soups, jellies and fruits at the end of the meal.

So why the distinction? Why can’t the experience be the same for everybody? The editor of this site found out how frustrating things can be with this article.

Chow Mein - strictly for non-Chinese

It appears that the Two Menu system prevails mainly due to an underlying fear that the public will not like what they order, or moreover will be put off by the unconventional phrasing. In other words: they don’t think we can handle it. But isn’t that part of the fun? Ordering Three Treasures Harbour Style without knowing what it actually consists of? And surely, that’s why menu annotations exist...

Many members of the community, including restaurant managers, will agree that there has been little innovation since the first boom of Chinese restaurants and takeaways. Both the industry and Chinatown itself seem to be in a rut. Modernisation is desperately needed in both cases.

Some restaurants are doing this and setting a standard for everybody else, but the proliferation of buffet restaurants means that the majority of footfall tends to go for the garish temptations of all you can eat deals. But for those looking for quality, there are few restaurants that you can trust.

These are the ones responding to the evolving sensibility of Mancunian punters. Restaurants now face the complex task of catering for an ever demanding, ever curious public. Not only that, but the massive increase of Mandarin Chinese into a community that was predominantly Cantonese.

It seems that the Chinese restaurants of Manchester are perhaps undergoing some kind of existential crisis. Their identity no longer swings between the rigid and dated ideas of ‘English’ and ‘Cantonese’, because what does it really mean to be either of those things anymore?

But one thing is for sure; the future of Chinese restaurants depends on their ability to move forward and respond to the demand of modern diners, this includes committing to providing the same experience for everybody...

Or if in doubt take a Chinese friend along.