Jonathan Schofield on a Manchester connection with a twist in the tail

History often plays tricks. What it loves best of all is to repeat itself, giving humanity a slap across the face saying 'surprised you again, didn't I?' Sometimes it repeats itself in unexpected ways. Thus in the UK we have two UK Prime Ministers, aged 55, separated by 102 years, experiencing similar and very personal assault by pandemic. What has happened to Boris Johnson in London in 2020 happened to Lloyd George in Manchester in 1918.

‘The Prime Minister is suffering from an attack of influenza accompanied by high temperature, and complicated with a sore throat'

In September 1918, still two months before the end of World War One, one of our most celebrated Prime Ministers, Lloyd George, visited Manchester to receive the Freedom of the City.

Lloyd George was by birth a Mancunian, but only just. He had been born at 5 New York Place, Chorlton on Medlock, 1863, as David George. He wasn’t there long. Both his parents were Welsh and they took the young David back home to Pembrokeshire while he was still a baby. His father died shortly after of pneumonia (more respiratory disorder) and the family moved to Uncle Richard Lloyd’s in Caernarfonshire. George’s uncle was a huge influence on young David so he adopted the name Lloyd in later life.

Despite not feeling quite himself, PM Lloyd George was still in buoyant mood on his arrival in Manchester on Thursday 12th September. Since the Battle of Amiens on 8th August, German resistance on the Western Front had started to crumble and they were in open retreat. The end of the war was still two months away but the PM could smell victory.

The Manchester Guardian reported his visit.

‘The Prime Minister, Mr. Lloyd George, yesterday received the freedom of the city of Manchester, and afterwards attended a civic luncheon at the Midland Hotel. In the course of the afternoon he fulfilled a number of engagements in the open air, in spite of repeated rain storms, and was very much cheered by large crowds. It was a return, with a vengeance, of the native.’

Somewhat appropriately, given the showman character of Lloyd George, a politician with a very interesting private life (rather like Boris in both instances) the main addresses were held at the spectacular Hippodrome on Oxford Street.

The PM was feeling the love. The Manchester Guardian wrote: ‘Mr. Lloyd George, who was loudly cheered, said: it is over half a century ago that I became a citizen of Manchester. I subsequently lost that privilege to circumstances of which I had no control (laughter) but I am deeply grateful - I am proud - that the Corporation of Manchester, have restored to me my lost citizenship of “no mean city” (cheers) - a city famed throughout the world for its enterprise in many spheres of activity, in commerce, in industry, in politics, in art. Manchester has had a leadership in some of the great movements of the past. Manchester has never been afraid of new ideas in the past, and I sincerely hope she will show the same courage in the future.’

It was a proper group hug of an occasion but there was a problem. Lloyd George was starting to feel short of breath and unwell. ‘We greatly regret to announce that in the evening Mr Lloyd George, owing no doubt to the exhausting duties of the day was taken ill and had to go to bed. This necessitated his absence from Reform Club (now Grand Pacific restaurant) in the evening.’

He was more than 'unwell', he had Spanish flu which would carry off almost a quarter of a million Britons and tens of millions globally. The Prime Minister was treated in Manchester Town Hall. Sir William Milligan, a Manchester-based doctor and flu specialist, was called in but the PM’s condition worsened and he was put on a respirator. Traffic was diverted from moving around Albert Square to give Lloyd George some peace as the situation became ‘touch and go.’

Of course, how close the PM came to losing his life was only released later; there was press collusion in not giving the Germans any potential of using the British leader’s incapacity as propaganda. Not that it was completely covered up. The Manchester Guardian released a statement from Milligan which seems uncannily familiar: ‘The Prime Minister is suffering from an attack of influenza accompanied by high temperature, and complicated with a sore throat, and is at present confined to bed, and is therefore obliged to cancel all appointments.’

Lloyd George would spend nine days in Manchester Town Hall. As he got better, he would 'stare out of the window at the statue of his fellow Liberal and inspiration John Bright.' Cabinet Government took over, although the PM was kept informed of what was happening. He returned to London on Saturday 21st September, but was still too unwell to continue with his full duties and took a further 'week’s rest in the country.’

Boris Johnson, we trust, will also recover but might need a longer recuperation period, as David Lloyd George did, before he can resume his full duties.

The historical echoes between 1918 and 2020 are fascinating, but one aspect of Lloyd George’s visit shows that some of the hopes of the time have not worked out.

In a comment piece on 12th September 1918, the Manchester Guardian writes: ‘Our modern civilisation is under a vow to reconstruct the moment the war is over, but it is at any rate something that in the last 30 or 40 years a career like that of Mr Lloyd George has been possible in England. There must be some oxygen in our society, clear flues, and a good strong draught, that so small a spark of life should have been fanned into such a flame.

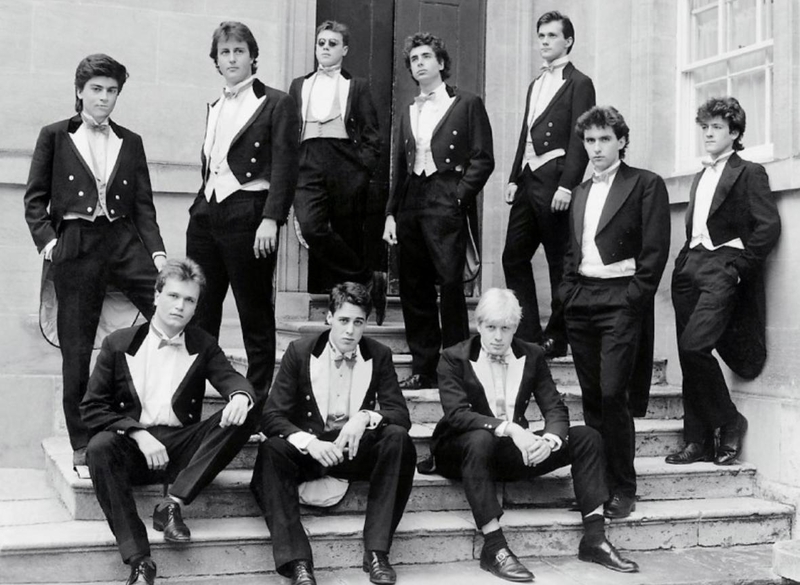

'We seem to be catching up the United States with its Lincolns, its Garfields, its Grants, and its sure, straight road from the log cabin to the White House. There is lots of caste still left in England, but it is being swept into holes and corners; into social life, for example, where it does no great harm; into private schools; in some villages, where we shall have to catch up with it someday. There is no tolerating it at all in really great affairs.’

In other words the Manchester Guardian is saying that the rise of a commoner such as Lloyd George, born in a terraced house in a working class corner of Chorlton-on-Medlock, proved that it was merit that should henceforth be the prime consideration for great office - not background. The Etonian and private school strangehold on Government since 2010 shows that five generations later ‘caste’ is still a long way from being ‘swept into holes and corners.’

Jonathan Schofield conducts regular tours of Manchester and the North West of England. You can buy vouchers for his tours for when the emergency ends here.