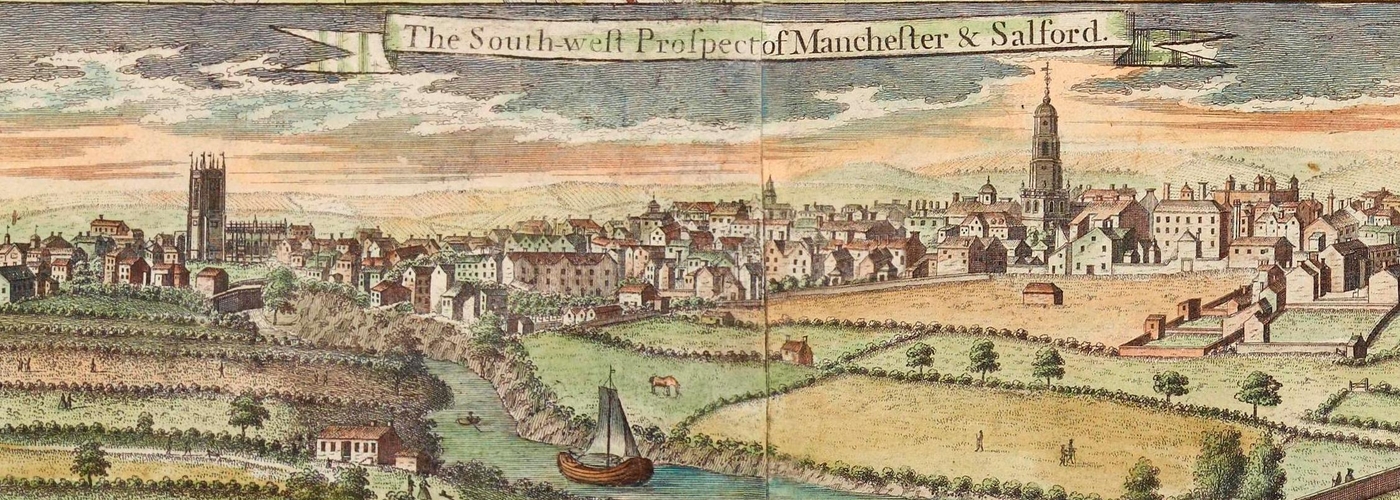

Part four of Jonathan Schofield’s history of the city (1660-1746)

AFTER the wild revelry of the restoration of the monarchy with Charles II in 1660 (as described in the previous chapter of this history), Manchester became bickery.

In some respects the next few decades in the annals of the history seem to revolve around tedious rows in the Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral) over minor doctrinal affairs and who should be the boss.

Yet, during this period, Manchester was growing, flexing its muscles, becoming the dominant force in the region. It was also becoming famous nationally for its ‘Manchester Cottons’ - a mix of flax and wool that weren’t true cotton at all.

When the author of Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe, travels through in the 1720s, this is what he says:

‘The increase of buildings at Manchester within these few years, is a confirmation of the increase of the people; the town is extended in a surprising manner; abundance, not of new houses only, but of new streets of houses, are added, a new church also, and they talk of another, and a fine new square is at this time building, so that the town is almost double to what it was a few years ago.

'You have here then an open village, which is greater and more populous than many, nay, than most cities in England, not York, Lincoln, Chester, Salisbury, Winchester, Worcester, Gloucester, no not Norwich itself, can come up to it; and for lesser cities, two or three put together, would not equal it, such as Peterborough, Ely, and Carlisle, or such as Bath, Wells, and Litchfield, and the like of some others.’

In the 1740s industry takes a step forward when merchants start handing out pure raw cotton to handloom weavers. It’s a big moment as the handloom weavers - self-employed independent-minded working class folk - will become a significant presence in the coming decades and a chief element in the protest about the lack of representation at Peterloo in 1819.

There were some fascinating characters around in this period (as in any other). One was Lady Ann Bland, the only child of Sir Edward Mosley and inheritor of the Mosley estates. She married Sir John Bland, a drinker and a gambler, as she found to her cost. Yet she was ‘a strong woman of great character and managed to hang on to her own fortune’.

She also supported the Hanoverian succession (William of Orange, Queen Anne and then George I) and therefore wouldn’t worship at the Stuart Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral). She built St Ann’s Church (consecrated 1712) as an alternative place of worship. It was the first Classical style church in Manchester. This led to the laying out of St Ann’s Square in the process – some sort of town planning had arrived in Manchester.

She frequently wore orange as a political gesture and as a snub to her rival, Madame Drake

The coincidence of her name, the Queen’s name (at the time), and the saint’s name was no accident, as Ann Bland wanted to be remembered: this was the most important reason behind the moniker. Thus the church and the square are spelt Ann not Anne, a point ignored by generations of Mancunians and especially would-be writers who want to write for Manchester Confidential.

Ann Bland also introduced the ‘harmonising assembly’ and was, as one account put it, an art collector. She was also the first lady of fashion and imported a doll from Paris every year with the latest fashions. She frequently wore orange as a political gesture and as a snub to her rival, Madame Drake, who worshipped at the Collegiate Church and would wear Stuart tartan (and also smoked a pipe and refused to drink tea preferring beer).

The split between those who supported the old Stuart dynasty and those who stuck by the arrangement made during the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (that had eventually delivered the Hanoverian succession) underpinned the early years of the 1700s.

The confusion over allegiance was summed up by Manchester writer John Byrom, whose house still survives as the Old Wellington Inn, close to Manchester Cathedral.

God bless the King, I mean our faith's defender!

God bless (no harm in blessing) the Pretender!

But who Pretender is, or who is King,

God bless us all, that's quite another thing!

In 1715, the Stuart rebellion reached Manchester in the form of a mob led by blacksmith Thomas Syddall, causing a riot and arson. Syddall was executed and his head placed on the market cross. It remained there until 1745, when another Stuart insurrection reached Manchester. This time it was a much bigger affair.

Charles Edward Stuart, the so-called Bonnie Prince Charlie, landed in Scotland from France to try and wrest the throne from George II. He marched south gathering volunteers.

The advance party arrived in Manchester on 28 November 1745 and consisted of ‘two men in Highland dress, and a woman behind with a drum on her knee’. The rest of the army and the prince soon followed.

People appreciated having the celebrity of the Prince amongst them and there were ‘gatherings and illuminations’, but there was less enthusiasm for his cause than he’d supposed. Only 300 volunteers joined him. They advanced as far as Derby and then, faced with a far larger British army, retreated.

As they returned through Manchester they demanded £5,000 and took a hostage to ensure payment. In 1746, the Stuart cause would be extinguished permanently at the Battle of Culloden, not far from Inverness. The Manchester men were captured at Carlisle, the officers tried for treason in London, and hanged, drawn and quartered.

One of the executed was James Dawson, the fiancé of Katherine Norton. The pair became a famous song. Nine traitors were to die on the same day as Dawson. Miss Norton followed the hurdles on which the condemned were dragged from prison to gallows at Kennington. She watched as her lover was half hanged, stripped naked, his stomach opened, his heart ripped out and his head cut off. As one report goes, ‘she got near enough to see all the dreadful preparations without betraying any extravagant emotions; but when all was over, she cried, ‘My dear, I follow thee! I follow thee! Sweet Jesus, receive both our souls together!’

Norton’s death by broken heart was marked by the nationally popular The Ballad of Jemmy Dawson with lines such as, ‘And ravish'd was that constant heart, She did to every heart prefer; For though it could its king forget, 'Twas true and loyal still to her.’

The heads of two of the officers, Deacon and Syddall, were returned to Manchester and impaled on the roof of the Manchester Exchange as a warning to other Stuart sympathisers.

Syddall was Thomas Syddall, the son of the aforementioned Thomas Syddall, who’d been found guilty of high treason thirty years earlier. Syddall junior, ‘a barber (who) had supported a wife and five children in a creditable way’, was hoping amongst other things for vengeance. This pair have an air of uniqueness about them. Never before, or since, have two family members had their heads displayed in Manchester, across a generation, over a cause that never had the slightest chance of success. It’s a metaphor for pointless sacrifice.