A rant, an investigation (sort of) and some assorted observations

The music in your restaurant is too loud. There, I said it.

I appreciate I sound like a boring old fucker but hear me out. I am a loud person. I like listening to loud music and going out to loud places. Except when I eat. When I eat I like to be able to hear the people I'm eating with and recently I can't because everywhere's too loud.

Brief tangent. There’s an origin story to this rant / investigation (the latter a loose term) and like all good origin stories it begins in Zizzi, Birmingham. Picture the scene. It’s the night before my brother’s wedding, everyone’s stressed and my brother has decided to take my rents out for dinner.

Zizzi is busy but me, my brother (deaf in one ear) and my parents (elderly, both hard of hearing, my mom has a hearing aid) manage to snag a table. We sit down, look through the menu, and like any time I eat with my mom and dad, they start asking what things are. Except, that’s what I think they’re saying. I don’t know because I can’t hear them. The music in the restaurant is too loud.

A staff member comes to take the orders. Similar story. A round-the-houses back and forth when the staff member tries to confirm our order. Everyone tries to make small talk but after five to ten minutes of leaning in, muffled half-received conversation and shouting, everyone just concentrates on the food and agrees to talk the next day at the wedding.

A family left awkwardly looking at each other, defeated by the Zizzi sound system.

This is not an isolated incident. A recent dinner I went to was marked by a spray-on-jean clad saxophonist and his bongo-bashing bestie galivanting around a busy dining room, free-balling it to a Wonderwall house mashup. Please, someone stab me in the ears. Make it stop.

The music volume backlash

The topic of sound levels in restaurants is a contentious one. Everyone has a stance and much of the debate is positioned as a face-off between old and young. Jay Rayner in one corner bemoaning low light levels and pointing out which age group has the most money to spend. Ynyshire’s Gareth Ward in the other corner playing techno and winning Restaurant of the Year.

Both have a point. A great restaurant is a finely curated experience. From the plates the food is served on to the interior flourishes. Playlists in restaurants across this city are poured over by restauranteurs. Music can enhance a meal, even speed up the eating and drinking. But at what point does it do the opposite?

Just had a lovely meal at Exhibition in Manchester. Amazing food, great service. But the music was SO LOUD. Dear Joe @BaratxuriBar I love your food and am happy to pay >£100 a head but the music makes me hesitate about going back. Maybe make the music that loud after 10pm?

— Simon Beresford (@JSimonBeresford) November 19, 2022

The hearing loss charity Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID) will tell you 80 decibels (dBA) is the upper limit. That’s louder than a vacuum cleaner. Extended periods of being exposed to noise 85 dBA or above, according to the RNID, can lead to hearing loss, whilst noise over 90 dBA is akin to sitting next to a motorbike.

Earlier this year research by sound measuring app, Soundprint, found that London’s restaurants were the loudest in Europe whilst San Francisco’s topped the charts as the loudest in the world. 80% of 1,350 London restaurants were deemed too loud for conversation and half of the restaurants measured exceeded 80 dBA.

Campaigns like Pipedown have sprung up as a response to this. Backed by the likes of Stephen Fry and Joanna Lumley as well as those who suffer from hearing loss and hearing-related conditions like tinnitus. Conditions not limited by age.

A decibel investigation

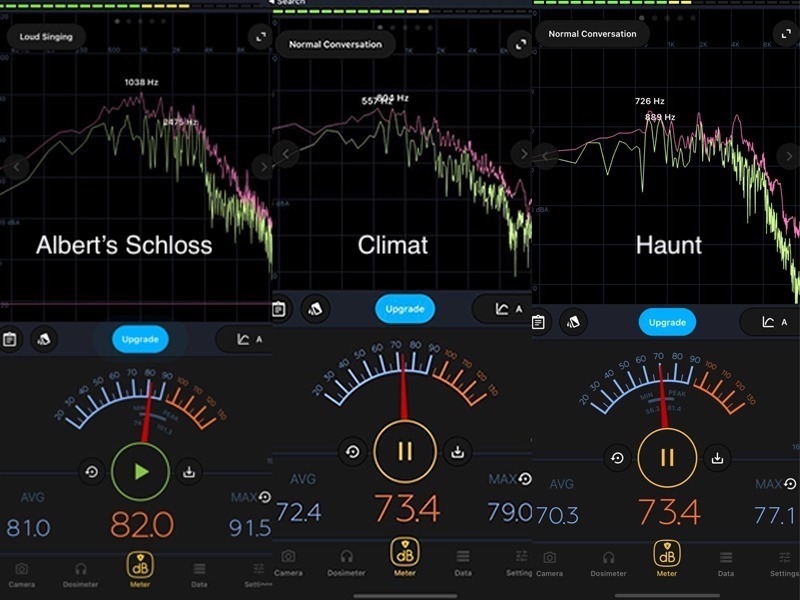

On the Soundprint app, designed so that user-submitted sound levels can go towards building a database of quiet places, you can see sound readings for restaurants across Manchester.

The sample group is questionable, mostly one recording in each venue at peak time. But what results is a rough guide to restaurant volume levels in the city. Of the thirty places tested within a 5-mile radius of the city centre, the highest reading is Shoryu (90) and the quietest is a split between Tampopo in the Corn Exchange, Vegan Shack and Yo! Sushi (69).

Of the 30 restaurants within this radius, the average recording on Soundprint is 79 dBA.

A modest investigation of our own using the Decibel X app returned similar results.

New Peter Street multi-kitchen concept Exhibition was the loudest at 90 dBA whilst Tahi was the quietest at 71 dBA. It’s also worth noting The Lombard Effect in all of this. The involuntary response in loud situations whereby people unconsciously speak louder, as well as altering voice pitch and syllable length. A phenomenon where noise breeds louder noise. Hawksmoor's hive-like main dining room is a good example.

A 2022 Soundprint analysis of 10,000 plus submitted sound recordings from US-based hospitality venues meanwhile, comparing objective sound levels and users’ subjective views on loudness, found that a venue 70 dBA or below was considered ‘great’ for conversation. Food for thought for hospitality.

Changing restaurant experiences, the acoustics of industrial design and a reactive approach

If you’re wondering why restaurants seem louder of late, here’s a few potential reasons.

One reason is the pandemic. “It’s change that’s the crucial thing with noise,” according to leading psychologist Professor Andrew P Smith at Cardiff University who has been studying the effects of noise on wellbeing since the 1970s.

“We adapt to living in noisy environments, but it only takes a slight change – a period of quiet – to find that very distracting. And I think there will be an adverse reaction to the return of noise – not just greater annoyance, but less efficiency at work, in education, in our sleep, as well as more chronic effects.”

Another reason could be architectural acoustics. Concrete, a material widely used in modern industrial-inspired interiors is bad for sound absorption and good for reflecting, meaning it’s likely to contribute to the overall din. The use of sparse, former industrial spaces combined with hard, minimalist interiors can have a similar effect.

There are options to address this. Holly Hallam, Managing Director of interior design agency DesignLSM explains:

“We strategically plan effective ways to manage the acoustics within the interior design – this includes the specification of sound absorbent materials when upholstering furniture, adding felt under tables, looking at softening the hard surfaces to reduce the acoustic bounce, as well as discreetly integrating acoustic paneling to places such as the ceiling or behind artwork.”

Granted, not everyone’s got the money to be felting the undersides of tables. Especially in the current climate. But if you’re keen to experience this in action, have a feel under the tables in Ducie St Warehouse next time you’re in. It can be a loud venue but it gets the acoustics right.

Another reason for louder venues is the fact eating out is changing. As Mike Shaw, chef patron of Manchester’s new Japanese-inspired restaurant MUSU points out.

"Dining experiences vary more than they used to. For me it’s about the customer having a great experience. This doesn’t necessarily mean tablecloths and staff standing like mannequins. If the staff are relaxed then I believe the customers will be.”

Mike points to Gareth Ward’s Ynyshire as a place that is unapologetically itself. You know what you’re signing up for when you go and if it’s not for you, then don’t go.

There’s also the trend for restaurants transitioning into late-night bars, something MUSU is part of with its Nijikai concept alongside other Manchester venues like Exhibition, Ducie St Warehouse and MNKY HSE. Mike says that the transition itself is important.

"We are a restaurant with a late-night offering, I don’t, and will never use the word club. It’s important we get the transition right from the restaurant to the nijikai party and our later bookings are told about the nijikai so there’s no surprises."

When done right, music in a restaurant can be an art form. James Galton, General Manager of Where The Light Gets In describes his restaurant’s music setup like second nature.

“This isn’t something that’s on our minds a lot now, purely because we have our system down. It’s a totally organic and reactive thing. Our playlists change depending on the day of the week, but volume is much more variable like the dimming of the dining room lights.”

“In terms of volume we talk a lot to our guests, with a story per dish, so it’s variable depending on the crowd and it subtly goes up if the room feels ready for it. Usually once the last hot course has left the pass at about 10pm, the guests are really relaxed at this point, so you can lull them with a bit of Enya or blast some Prince on a Saturday night to get the weekend party started.”

Update: The music in your restaurant is too loud for me.

(But, I appreciate I’m probably more sensitive to sound after the pandemic, the price of acoustic architecture to offset a minimalist, industrial fit-out is expensive during a hospitality crisis, and your business might be navigating a transitional phase between restaurant and bar in order to survive and prosper. Perhaps turning the volume down one or two decibels is a beneficial compromise for everyone?)

There, I said it.

Follow Davey on Twitter and Instagram: @dbretteats