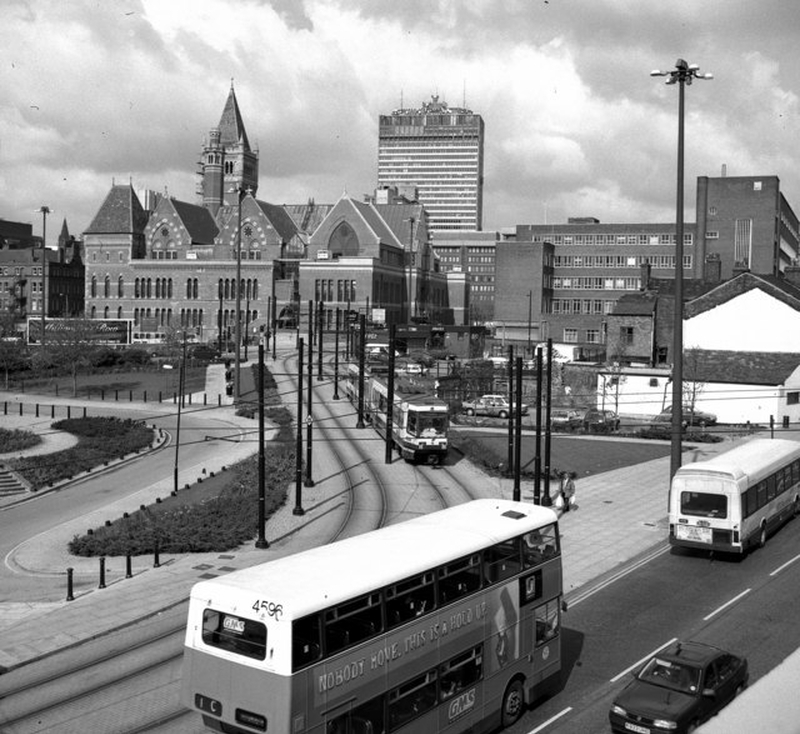

The Metrolink, bombs, Trebles, arenas, concert halls and more

THE nineties are dominated by the IRA bomb of 15 June 1996. This injured 212 innocent people and caused £700m of damage in the prime retail area of the city. It was a miracle nobody died.

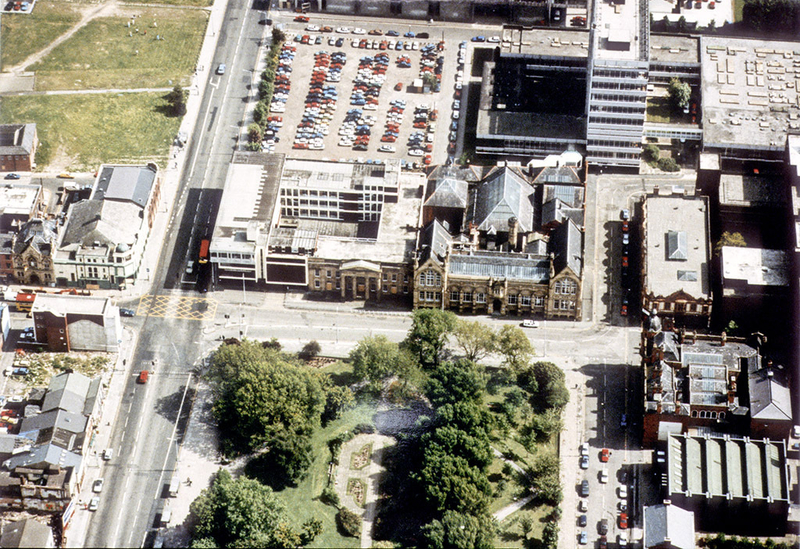

The reaction was immediate and the City Council, businesses and central government all pulled together to get a rebuild under way and make the city centre an easier place to enjoy. This was largely completed with much success by the turn of the millennium.

It’s become received wisdom that the bomb was the turning point for Manchester city centre. This is nonsense and ignores the fact the building blocks of future success had already been laid in the previous ten years through Olympic bids, the city working with the commercial world, the development corporations and, just as importantly, a return of an urban sensibility and movement back to city centres.

(For an in-depth discussion of the 1996 bomb and its aftermath read this.)

A year before the big bomb (there had been two smaller IRA bombs in the city in 1992) Manchester Arena (now AO Arena) opened. This was then the largest city arena in the country and by the end of the decade the busiest arena in the world. Earlier again, in 1994, the Manchester Velodrome had opened, now the National Cycling Centre and an Olympic goldmine. Both these projects revealed the value of those Olympic bids.

Late in 1996, the Bridgewater Hall launched and for the first time in almost 150 years Manchester’s orchestras, particularly The Halle, had an auditorium of international standard.

These projects showed the city was ticking the boxes in the areas modern and dynamic cities should offer. Despite the failure to secure the 2000 Olympics, which were awarded to Sydney, the city went on to win the right to host the 2002 Commonwealth Games, a prize that provided some light in the dark months of 1996. Meanwhile, the superb Streets Ahead festivals showed the city centre, not the parks and suburbs, was again the place in which to showcase pageantry and spectacle.

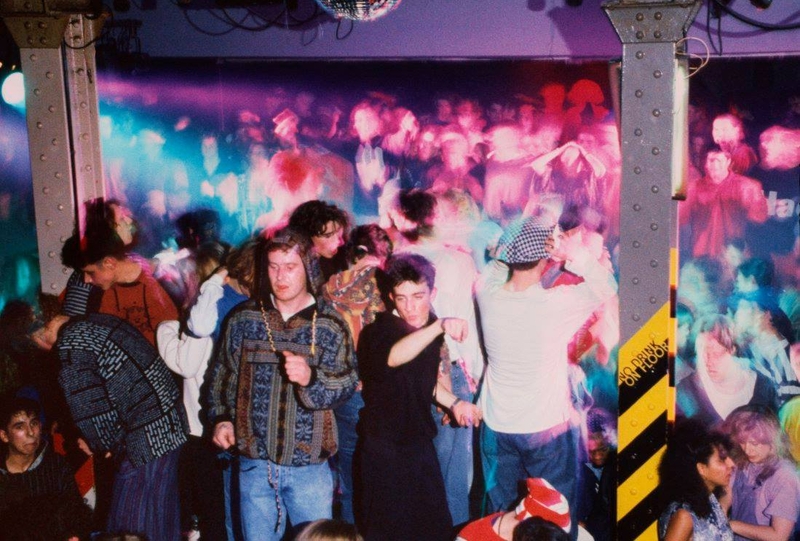

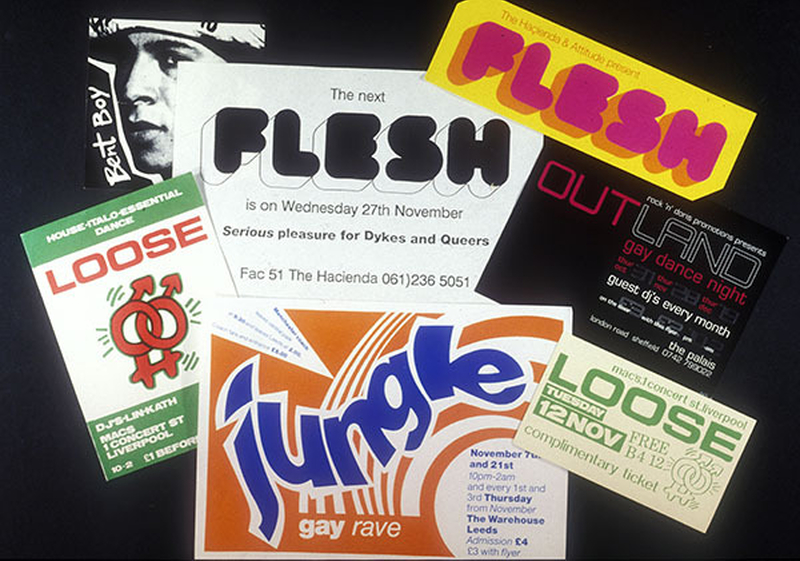

The Hacienda might have closed in 1996 but there was plenty going in the clubs, with nights such as Mr Scruff’s Keep it Unreal, the Unabombers’ Electric Chair and Homoelectric, plus Flesh (before the Hacienda went bump, some five years after Factory Records had crashed). As the decade wound on the heavy gang presence seemed to lessen. In the pop charts two Manchester groups kept things exciting but in very different ways; Take That wowed one audience, while Oasis wowed a different one.

Electric Chair and Homoelectric showed the vibrancy of the Village scene. Manchester’s gay village came fully out in the nineties when in 1992 an assertive Manto bar on Canal Street opened with plate glass windows allowing people to see in and out. The Mardi Gras festival (now Manchester Pride) blossomed into a key event on the Manchester calendar. The same could be said for Chinatown and Chinese New Year. Meanwhile the Northern Quarter began to properly stir as the left field heart of the city.

The decade closed with confirmation of the rampaging rise and rise of Manchester United under Alex (later Sir Alex) Ferguson. After knocking Liverpool FC definitively ‘off their perch’, as he put it, 1999 was United’s annus mirabilis.

It hadn't been quite the same for Manchester City, who had suffered the indignity of dropping into the third tier of English football. In 1999 they beat Gillingham in a play-off final to make it back up a division and begin a slow rise to current dominance.

City fans' delight with the result of the play-off final was curtailed by ‘that bloody United’ when the latter, for the first time in football history, secured the Treble of League, FA Cup and Champions League. The parade on the city streets was said to have attracted a million people.

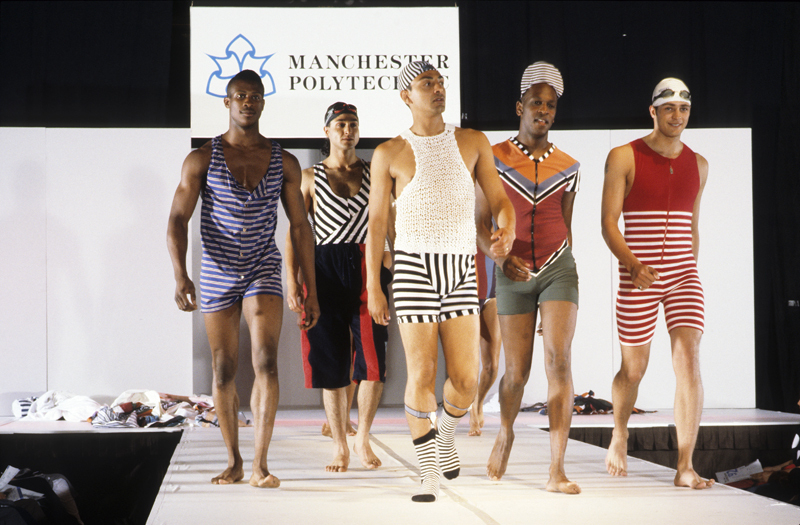

Image credits: Visual Resources Collection at Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections OR Geograph.org. All rights reserved.