John Blundell on how pangolins and a health crisis have more in common than you think

The COVID-19 pandemic has piqued my interest in public health issues. It’s worth remembering that the idea of it being the responsibility of the state to tackle public health crises originated here in Manchester, rather than in far flung corners of the world, as part of the newly industrialised metropolises of Britain.

In Rochdale, the alderman chose to build the splendid Town Hall rather than a sewerage system

Manchester, as well as being filthy rich a century or two ago, was also just filthy. Alexis de Tocqueville, who became a French minster, said “from this filthy sewer pure gold flows” when describing our great city. Around the time of his backhanded compliment, following the Municipal Corporations Act (1835), Manchester was incorporated, which (eventually) meant sewerage and sanitation became a consideration of the city’s policy makers.

Unsurprisingly, sewers were not high on upper classes’ agenda, as it didn’t affect them despite their wealth having been generated by the booming economy. Infamously, in Rochdale, the alderman chose to build the splendid Town Hall rather than a sewerage system. We ended up with both in the end, but it reveals the middle classes’ priorities at the time.

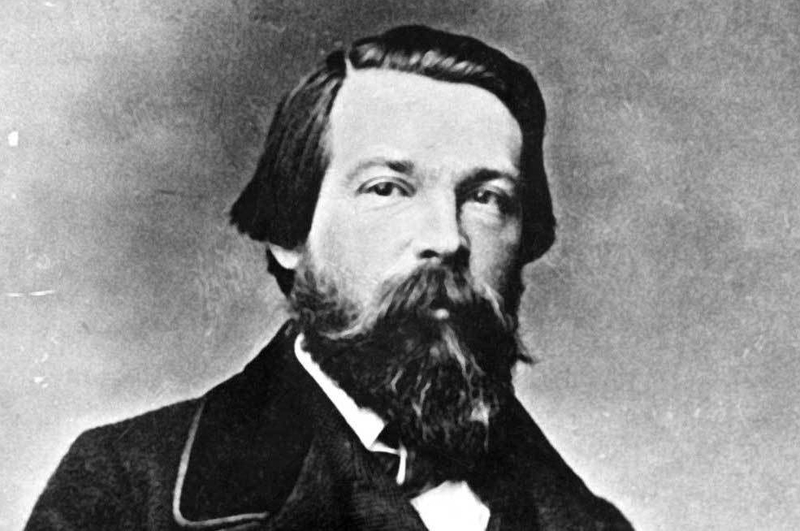

Off the back of the squalor in Manchester, Friedrich Engels wrote a book called the The Condition of the Working Class where he wrote (in a revised edition) 'repeated visitations of cholera, typhus, small-pox and other epidemics have shown the British bourgeois the urgent necessity of sanitation in his towns and cities.' The sights he and Marx witnessed in Manchester were so wretched it inspired the original communist text Das Kapital.

Another Mancunian, Edwin Chadwick, was behind the revolutionary Public Health Act (1848) - making sanitation, health, standards and safety a statutory concern of the government. Still to this day councils must have a director of public health by law with certain diseases and addictions they must tackle.

Chadwick convinced the Poor Board to allow him and a Rochdalian doctor called James Kay-Shuttleworth to inquire into a recent outbreak of typhus. His report, named The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, is what lead to the new legislation and the Central Board of Health being established.

Britain now tackles public health issues successfully, but it wasn’t always that way. The speed at which China has developed economically is nothing short of a miracle but, like we were, they have been slower to enforce corresponding laws designed to protect the public’s health.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a local public health issue (such as the selling of wildlife for human consumption) that has gone global due to the nature of today’s economy and global travel. Coincidentally, the initial outbreak was in Wuhan, Manchester’s sister city, a place that has grown rapidly in recent years

I found The New York Times' recent article Coronavirus: Revenge of the Pangolins? fascinating. It perfectly frames what has happened by quoting President Xi Jinping as saying “we can’t be indifferent any more,” referring to the Chinese’s insatiable desire for consuming certain wild and exotic animals.

The article puts a spotlight on the trafficking and consumption of pangolins, which may have been the source of the virus, which is outlawed in China but not properly enforced. The foetuses of pangolins are believed to make men more virile, their scales are thought to have medicinal properties and its meat used to impress guests.

China’s ancestors took the opposite view of pangolins. The alchemist of the Tang dynasty (7th century), Sun Simiao, said “there are lurking ailments in our stomachs. Don’t eat the meat of pangolins, because it may trigger them to harm us” and others believed it may cause convulsions and a fever.

The balance between environment and society has clearly been out-of-kilter but it wasn’t so different here. William Cowhered, the reverend of the ironically named Beefsteak Chapel in Salford, was a prominent vegetarian in the early 1800s and he believed it was a form of temperance.

In 1847 The Vegetarian Society was established off the back of his movement, with their first public conference being held right here in Manchester. Unsurprisingly, storing then eating meat in the slums of Manchester sometimes made you ill. In a similar vein to Cowherd’s words of wisdom, China’s yesteryear soothsayers probably were on to something too.

The idea of it being the responsibility of the state to tackle health issues, you could argue, was born out of the experiences of the working classes here in Manchester but these disasters didn’t spread as far and wide. The difference today is that we have never lived in a more connected world where somebody else’s actions, no matter how far away, can have consequences for us all.

Hopefully, like Chadwick’s national campaign, what will rise from the ashes of this pandemic is a global response to how we all treat and exploit our world.

Follow @johnblundell993 on Twitter

Occasional contributor John Blundell is a Labour councillor for Smallbridge and Firgrove, and the Cabinet Member for Regeneration, Business, Skills & Employment on Rochdale Council.