Even Jonathan Schofield can't find any precedent for these times in Manchester's history

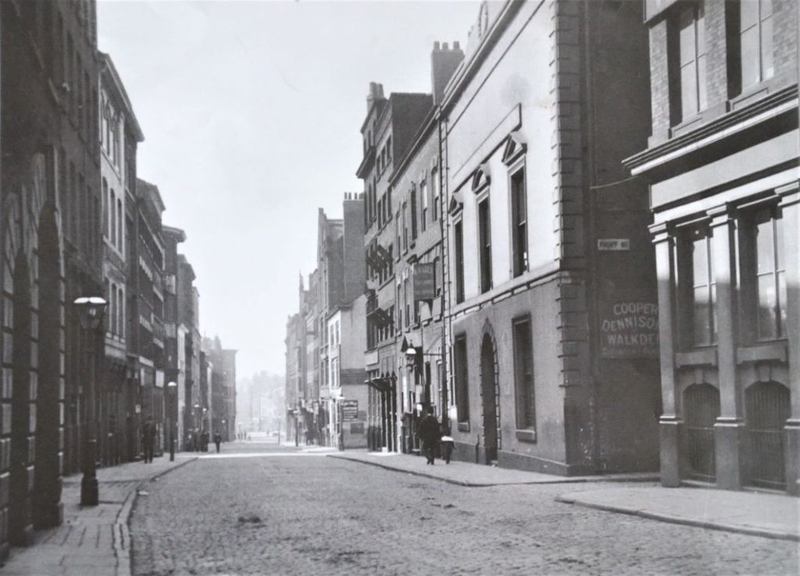

The image below shows a quiet day in 1906. Cannon Street should normally be packed with commercial and private transport and crowded with people. We count six humans in view. It’s a quiet day in 2020 and Manchester’s streets have emptied in the picture above. There are even fewer humans in the view.

It’s lovely and sunny in both. There is one difference. The picture of Cannon Street 1906 was taken on a Sunday. Nobody’s there because nobody was ever there on a Sunday. Shops were closed and people were taking their day off seriously. In 2020 the streets are artificially empty, they shouldn’t be like this.

Streets rarely have been empty except on Christmas Day, Sundays and Bank Holidays. Before the Sunday Trading Act 1994, most town and city centres were dead. You could walk down the middle of Market Street and not see a soul. Suburb and country pubs might be rammed, the parks busy, but city centres, away from the capital and a few tourist locations, were ghost towns.

Enforced ‘lockdowns’ have been rare in the UK. During the heaviest night of Manchester's wartime bombing, 22nd/23rd December 1940, people carried on mostly calmly. These words from Ron Train following the first night of terrible destruction are telling.

'The following morning everybody went off to work. Streets were littered with broken glass, shops wide open with notes in the spaces where the windows used to be announcing ‘OPEN AS USUAL.'

'The company that I worked for did a fair amount of work for the breweries so we went to our first job in Jackson Street to jack up the damaged roof. Another casualty was the Hare & Hounds on Shude Hill. This was very badly damaged as we had to replace a large part of the roof, but life carried on.'

There are reports of people putting on their shirts and ties and work frocks and coming to their jobs through rubble strewn streets to stare at the gap in the street where their office or warehouse used to stand.

At the beginning of the war theatres and places of entertainment had been closed (although not pubs) and football and other mass sports halted. This was in case they were hit by bombs. However, within a very short time the rules were relaxed as the government thought it better for morale for people to have recreation. Theatres and cinemas reopened and football was allowed in district leagues with maximum capacities of 8,000.

That was war. Our last major pandemic was the so-called Spanish flu of 1918-19. A quarter of a million people died in the UK (50m-80m globally perhaps). In the City of Manchester (not Greater Manchester) 2096 people died in 1918. In 1919, during the second wave of the virus, 1062 people died in Manchester out of a total of 10,854 city deaths.

Yet, back then, there were no measures in place to ‘lockdown’ the country. This was down to, yes, ignorance of the virus, but also due to war. Countries such as Britain, France, Germany and many others had lost hundreds of thousands of mainly young men in WWI between 1914-1918 and they didn’t want to cause more distress by telling people the true nature of the pandemic. They deliberately withheld information.

The number of the dead was exacerbated by the end of the war as millions of infected soldiers were shipped home or to other areas of the world. But there was no lockdown, people went about their business.

My great-aunt died. Manchester writer Anthony Burgess wrote bitterly in his autobiography about the death of his mother and sister: ‘There was no doubt of the existence of a God: only the supreme being could contrive so brilliant an afterpiece to four years of unprecedented suffering and devastation.’

Throughout the nineteenth century the great killer was consumption, or as we know it tuberculosis, but the epidemics that hit Manchester came via water-borne cholera. There were cholera epidemics in 1832, 1849, 1854 and 1866. The 1849 outbreak was the worst of these, killing 52,000 out of a UK population of 27m. There were no lockdowns during any of them.

The 1832 outbreak in Manchester is instructive. Out of a population of almost 150,000, 920 died, that's less than 1%. This was in the early days of all-out industrialisation where shocking sanitary conditions combined with the most basic of healthcare. People lived shorter lives as well.

The 1832 ravages of cholera showed what can happen without adequate communication. There was a major riot in Manchester when a doctor at the Swan Street Cholera Hospital removed the head from the body of a three year old boy, John Brogan, to carry out investigation into the disease. During his burial the family discovered his head had been replaced by a brick. The hospital was attacked and severely damaged before the hero of the moment Father Hearne calmed the largely Irish crowd just before four troops of the Hussars arrived and it got much worse.

In the poor areas of the city and across Britain, poor people thought cholera had been spread by the rich to cull their number. This is similar in some respects to ridiculous stories from various parts of the world that COVID-19 has been artificially created to attack particular populations.

The 1832 ravages of cholera showed what can happen without adequate communication.

Across the whole history of Manchester I can find nothing in war or pestilence to echo the lockdown of 2020. Save one, although it’s more a quarantine than a lockdown. The bubonic plague hit the town in 1645.

‘A pestilence visited the town; and from an Ordinance of Parliament, July 9, it raged with such violence that for many months none had been permitted to come in and go out of the town. Most of the inhabitants living upon trade are not only ruined in their estates but many families are likely to perish for want who cannot be sufficiently relieved by that miserably wasted country.' Parliament voted a grant of £1000 for the relief of Manchester.

Aside from Sundays, Bank Holidays and other special occasions, there has never been anything like this situation in war and peace. Maybe we could, with a flight of fancy, go right back to when the Romans abandoned Manchester and before the Anglo-Saxons arrived when there was very probably nobody at all here. Emptiness defined.

The comfort in 2020 is, of course, that we live in times with a large health service and sophisticated medical practices, where the expectation is that we will find a cure for COVID-19. It is only a matter of time. Of course some have suggested, and still do, the tough cold way of not dealing with Spanish flu and cholera in the past might lead to a short sharp shock and let this pandemic wash through the population quicker; thus normality is resumed earlier.

It says much for global life in 2020 that we’ve moved on from that. Of course there is the practical matter of ensuring the NHS can cope, that’s a numbers game. But we also want to avoid mass graves, vast numbers of dead and all the misery that involves; we also need to avoid social unrest. Early days for all that of course, but much of what lies behind the lockdown is compassion for each other. That’s different, that's reassuring.

In both the main pictures here the days are temptingly sunny. For us that is becoming a tease as we are confined to home - if we are complying. I look at the small boy on the right in the 1906 picture, holding his dad’s hand, dressed in a little sailor suit and for some reason I hope he escaped becoming a victim of war and pestilence between 1914-18. Let's hope he went on to have a fulfilling life. The lesson is we always come out of this.