NUDE male races, public hangings, 100,000 horse racing enthusiasts and 300,000 protestors. The elusive grandstands at Kersal Moor saw it all.

There was a strange unheard of race in which scantily clad women took part.

From at least 1687 to 1847 Kersal Moor, four miles outside Manchester and offering views across much of Greater Manchester, was the scene of ‘unbridled merriment’ or ‘drunken debauchery’, depending on your viewpoint.

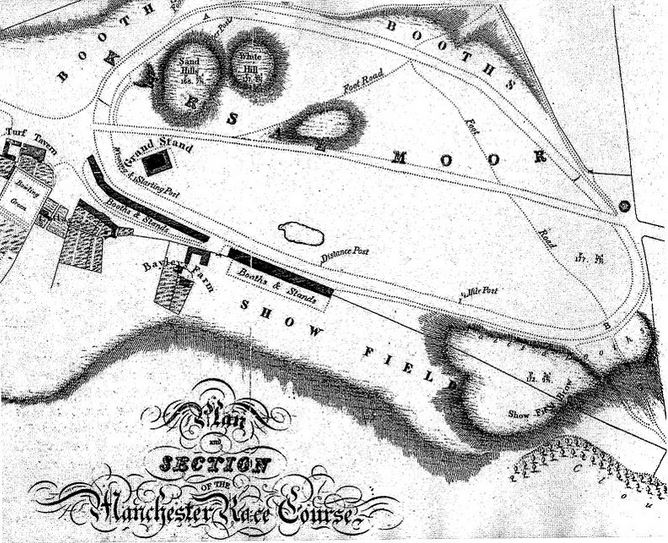

The grandstand in its final form after 1819 is glimpsed through the odd sketch or print, hence its elusiveness, and looks very handsome. Set on ten or twelve arches it supports a large main terrace. Behind this is another large structure on top of which is more seating at some considerable height. The building is surmounted by some sort of pediment and a flagpole. There were rooms with refreshments within the building.

It was a fine edifice, but there could be trouble, on one occasion in 1825, a railing failed and many people were injured - though none fatally.

The best picture from 1830 shows the riders charging towards the finish post under the grandstand, past a large temporary stand.

A Ladies’ Stand had opened in 1780, some years after the first stand had been erected at Kersal Moor, although sources might be muddled here and this may have been the first permanent stand to be built. Then again it may have also been temporary. What we know is this advertisement was posted: ‘The ladies’ stand on Kersal Moor will be opened on Wednesday next for the accommodation of ladies and gentlemen of the town and neighbourhood of Manchester, where coffee, tea, chocolate, strawberries, cream, etc, will be provided every Wednesday and Friday during the strawberry season. By the public’s most obliged and humble servant, Elizabeth Raffald.'

Kersal Moor

Kersal MoorRaffald has always been one of Manchester’s most celebrated characters. She was a businesswoman running pubs and indoor and outdoor catering, author of books including the first Manchester and Salford Street Directory and a hugely popular cookbook, The Experienced English Housekeeper. She died there in 1781, having, according to many sources, given birth 16 times.

The main race meets took place around Whitsuntide, the seventh Sunday after Easter, and brought huge crowds, with over 100,000 gathering at some events. As early as 1687, £40 prizes were given, a princely sum at the time.

There was huge fun to be had and huge amounts of drink drunk, there were betting booths and entertainment booths. In the mornings, until the practice was banned in 1835, cock fighting took place. The mass crowds meant also the sale of ‘obscene prints’, gambling with dice and a lively level of pick-pocketing.

A strange custom in the early years was nude male racing – whether fully nude is not clear – but this was an occasion it was said for ‘females to study the form of prospective mates’. Rumour is that when 65-year-old widow Barbara Minshull saw 6ft 4in Scot, Roger Aytoun, charging down the track she decided to woo the young man. Within days they were married, Aytoun attracted by her status as one of the richest women in the North and she attracted perhaps by the physique of a kiltless Scot. It was said he was so drunk during the marriage service he had to be held upright by friends. Minshull Street and Aytoun Street in the city centre mark their strange union.

On another occasion a local minister wrote, ‘there was a strange unheard of race in which scantily clad women took part’.

Meanwhile, before the races came to an end the stands witnessed other events, such as in 1790 when James McNamara was publicly hanged here for a string of burglaries and robberies in the area. Normally such executions took place in the county town of Lancashire, but a decision was made to make an example of McNamara who was hanged in front of vast crowds on ‘the large hill close to the Grandstand’. Not that it made much difference as one commentator noted. Joseph Aston writing: ‘No one could suppose that the example had any use ... as several persons had their pockets picked within sight of the gallows and the following night a house was broken into and robbed in Manchester’.

A national event took place when, according to one report, ‘the largest crowd the British Empire had witnessed’ gathered where the races were held. More than quarter of a million Chartist supporters it was claimed gathered on 24 September, 1838 – although the Manchester Guardian said there were only 30,000. The Chartists wanted fair, democratic, representation, votes for everyone, secret ballots, no property qualification for MPs, payment of MPs and equal electoral constituencies in terms of numbers of voters. All of their demands we now take as standard apart from one – the unwieldy call for annual parliaments. Speakers included John Fielden, JR Stephens and firebrand Feargus O’Connor. It passed off peaceably and was marked by music with ‘A New Song on the Great Demonstration’.

The city from Kersal Moor in the early 1850s

The city from Kersal Moor in the early 1850sSport other than horse racing has notable connections with Kersal Moor, not least that it hosted the second golf course in England after Blackheath with Manchester Golf Club, set up in 1818 by cotton spinner William Mitchell. It was also at Kersal where Broughton Archers practiced from the 1770s. Athletics, cricket, rugby and football have all been associated with the Moor and presently non-league Salford City FC occupy part of the site. In 2014 50 per cent of the club was bought by ex-Manchester United stars Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, Nicky Butt, Phil Neville and Gary Neville.

Salford City FC

Salford City FCMaybe notoriety is on the way back for one of Europe’s longest continuously used sporting locations with well over 350 years of running, jumping, hitting, and kicking.

A walk around a reduced Kersal Moor is still immensely enjoyable. Paths follow the old route of the race track and presently heather purples the hills. The best route to the moor is via Bury New Road and then left along Moor Lane. The distance from the city centre is around two and a half miles. Paths lead off on the right into the moor immediately after St Paul's Church with its odd double spire. The church was finished in 1852 and designed by William Walker.

This article is part of Lost & Imagined Manchester by Jonathan Schofield, to be published in October.