Jonathan Schofield welcomes the return of a city favourite and tells its story too

"Who would find eternal treasure, must use no guile in weight or measure."

These are the words around the dome of the Royal Exchange in the former trading hall. Not that you've been able to read them for a while.

Access to the trading hall, one of the jaw-droppers of Manchester tourism, is now allowed again

Access to the trading hall, one of the jaw-droppers of Manchester tourism, has been denied since March 2020. At long last, it is now open again to people other than those just attending a show at the theatre. People can now have a shufty from 11am-5pm from Monday to Saturday.

The restaurant, The Rivals, is not set to open until spring, but the cafe with the same name is open for coffees, cakes and some booze. The shop with its crafty emphasis is permanently closed.

More positively there will be events and these include Sundays. On Sunday 5 December there's a vinyl record fair including Charlatan Tim Burgess' Vinyl Adventures. There's going to be a Christmas fair in the hall too.

As stated, it's about time the hall is opened. Having taken tourists around the city since the bizarrely monikered "Freedom Day" in July, it has been very noticeable how many of the public sector institutions have been slow to re-open to their audiences.

Just about all the museums and galleries are still closed on Mondays and Tuesdays when most were open seven days previously. This has flummoxed guests taking a long weekend in Manchester. To see, say, the hospitality sector often with tiny resources trying so hard to open provides a contrast to the reaction of much of the public sector attractions in the last months.

Still, now we have the Royal Exchange back as a place to admire, to sit and take it easy and even, as the Americans say, seek sanctuary for a "comfort break".

So what’s the story behind the building?

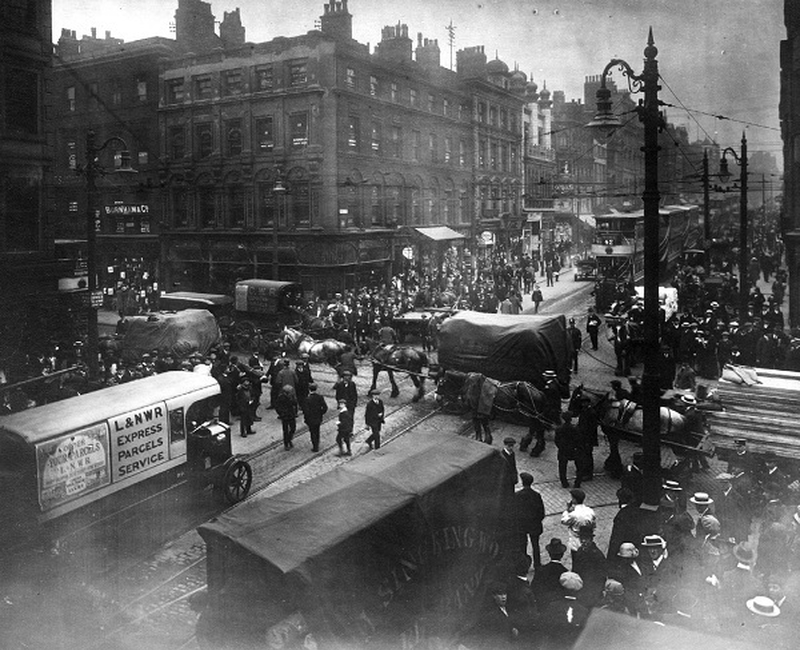

The Royal Exchange was the centre of the global finished cotton trade for centuries. It’s where on Tuesday and Friday members would meet to do business and swap news. It was a huge talking shop. The Exchange was expanded and rebuilt on several occasions and attracted manufacturers, merchants, engineers, shippers, bankers and insurers from around the world – often up to 15,000 per day. It was as big as business gets. At its height during the last decades of the nineteenth century up to the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s, it controlled more than 80% of all the world’s trade in finished cotton.

A picture from the 1920s shows the place packed to the rafters with traders – like a crowd on the terraces in a footy game. On any visit look out for the former trading board close to the ceiling on the western side of the room over the restaurant.

The heyday atmosphere was beautifully captured in the 1920s by HV Morton of the Daily Express as he followed a trader as he moved through the crowd.

"As I look down with a feint Olympic feeling from the Strangers' Gallery I try to follow one little man through his adventures on the floor. I see him moving through the monster, a part of it, yet to me the most important part of it because I am thinking of him as an individual and I watch him stop at various groups, edge his way, say his little bit and move on, watching, searching, trying to make money, and the whole thing so casual, so removed from roll-top desks and all the paraphernalia of the business.

"He stops to make a joke. Someone tells him a joke that makes him laugh just a little bit too much. He is anxious to please. Now he looks grave, and rubs his chin with his little hand and shakes his little head. Did someone try to sell him a pup? Sometimes a man comes to him or rather seems swept up against him in the chaos, and they bring out notebooks and look solemn. They have booked an order. He is, I am sure, having a good day. He is a cheerful little man. I watch him tell the same story time after time in different groups. Often I see him standing politely waiting until a conversation ends before he introduces himself. ’Change is the only place in Manchester where a man will not butt into a conversation, no matter how much he wants to. It is not done.

"And the little man, just as I am beginning to like him, just as I begin to hope that he is kind to his wife and always takes her home presents, when his pencil has been busy on ‘Change, goes and loses himself in the rather grim impersonality of the monster. And the voice of cotton goes on and on and on..."

The building we see today wasn’t the first one. This iteration was finished in 1921, designed by Bradshaw, Gass and Hope (they also did the old financial Exchange which now houses the Bull & Bear restaurant in the Stock Exchange Hotel on Norfolk Street).

This was the last in the line of several older and smaller structures stretching back to 1729 – the first of which had even hosted the severed heads of the 1745 Mancunian traitors in the Bonnie Prince Charlie rebellion.

This building is a classical structure with pilasters and elaborate detailing on the outside, and that beautiful trading hall inside complete with scagliola columns and three domes. It was built as though the cotton industry in Manchester would be a permanent, immovable force. Ah human vanity, eh?

In some ways, it’s a damned shame we lost the prior design because that had one of the UK’s grandest porticos. This graced and energised the view from Albert Square. It had to go though, as the directors wanted to snaffle all the available land for the present incarnation, so they demolished the portico and pushed the Royal Exchange out to the limits of the building line.

The trading room we see now used to be almost double the size with another three domes. The Royal Exchange lost its claim to be the biggest trading room in the world when a WWII incendiary bomb gutted the northern end of the structure. By the time of the rebuild, the telephone had arrived and people didn’t meet as often as they had, so the other part of the hall was filled with offices. The writing was on the wall in any case.

The Lancashire cotton trade was dying. Countries with easier access to the raw material and cheaper labour costs were catching up and taking over. Also, the UK industry hadn’t invested in newer production methods when it should have done. Two hundred and forty-nine years of history came to an end when the doors closed on 31 December 1968.

And then as a city, we were bloody lucky. With remarkable foresight, the fledgling Royal Exchange Company commissioned Richard Negri and Levitt Bernstein Associates to build a theatre in the old trading room. The result is that Manchester’s gained its own, internal Pompidou Centre (in design terms not function), which was opened in 1976 by Sir Laurence Olivier. The new structure was a fiercely individual, high-tech response to the vast chamber which surrounds it; a perfect tonal contrast to the older structure, and as sharp today as it was when it opened.

Of course, the bombs returned, with the IRA in 1996 when the domes and theatre were badly damaged. Two years and £30m later the building reopened, massively and cleverly brightened and freshened with the addition of more colour up high and better facilities.

This is all a bit personal for me. The Schofields used to be members and we had our own spec. The trading hall got so packed the columns were numbered or lettered to create an internal grid reference. Members would meet other members at a position indicated by the intersection of letters and numbers. The textile machinery company of J&H Schofield Limited would meet at J2. It’s a nice connection I can point out to guests and maybe even show them my dad's membership card. I then point out we went bust in the 1940s which was rather too soon for me to access any of that lost family fortune.

Royal Exchange Theatre, St Ann's Square, Manchester, M2 7DH. Open Monday-Saturday 11am-5pm with some Sunday access during events.