Jonathan Schofield writes about a vision that would have hugely improved the city centre

THE Northern Quarter could have been all park.

The city might oil the wheels for developers to construct more buildings but it won't create that proper city centre park

It would have been called New Central Park and filled half a square kilometre. This would have occupied the area between Piccadilly Gardens and Great Ancoats Street on the south and north and Shudehill and Newton Street on the west and east.

The proposal was made by Sir Ernest Simon and John Inman in their 1935 book The Rebuilding of Manchester.

Simon, and his wife Shena, must be included in the greats of Manchester civic life. Their money came from the family engineering firm. They were generous-hearted and hugely intelligent people who displayed indefatigable energy in attempting to improve the lot of Manchester's citizens.

When The Rebuilding of Manchester was published Simon had already been the chair of Manchester Housing Committee, the Lord Mayor and a Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health. It was his money through which Wythenshawe Park - including the recently fire-damaged hall - was bought for the city. He had even been a prime investor in Sidney and Beatrice Webb's New Statesman.

Green as far as the eye can see: the area that might have been a park

Green as far as the eye can see: the area that might have been a park.JPG) An expanded view of the area looking south west (both views from the car park over Shudehill Transport Interchange)

An expanded view of the area looking south west (both views from the car park over Shudehill Transport Interchange) Simon and Inman's book looked at various aspects of Manchester life in the 1930s with a particular focus on the appalling housing conditions in the densely populated inner suburbs. But they also realised the city centre needed urgent re-planning as well. They consulted with Max Tetlow, architect and town planner, over this.

We must, the authors wrote, 'improve the amenities of the city. (The) main proposal is the creation of two great central parks, with Mosley Street as a straight main road, three-quarters of a mile in length, connecting the two parks. The park in the south would lie between City Road and Chester Road occupying eighty acres of land, that at the north would be between Piccadilly and Great Ancoats Street. In each case there would be some notable building standing in the park facing the end of the central road, situated so as to terminate the vista looking along it in either direction with striking effect. At the south end might be erected an Exhibition Hall, which Manchester needs at present; while the north end would be an effective site for the proposed new Art Gallery or new Cathedral.

'It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of one or two fine central parks,' they continue. 'One has only to think of the effect of St James's Park in the West End of London, or of any of the great parks in the leading cities. These two parks would of course be expensive. But other cities are able to afford far larger parks than we have proposed. Why cannot Manchester do the same? The citizens of Manchester demand some such thoroughgoing attempt to make the commercial centre worthy of a city of the size and reputation of Manchester.'

The proposal is beguiling, the points made telling, the reasoning compelling. For Piccadilly Gardens' sentimentalists it's interesting to note how that space has been filled with commercial property on this plan as 'it is clearly too small to effectively function as a gardens'. So they take everything north to Great Ancoats Street, around 35-40 acres, ensuring a real park can be delivered.

.jpg) The proposed 1935 city centre plan

The proposed 1935 city centre planTwo years after The Rebuilding of Manchester, the Chamber of Commerce produced a lovely little book called Manchester, the heart of the Industrial North with a foreword by the well-known Yorkshire writer JB Priestley and gorgeous watercolour illustrations by Radcliffe and McKibbin. One featured a typical Manchester park and how it should be maintained. The park shown was Alexandra Park in Moss Side and seems to be exactly the sort of place Simon, Inman and Tetlow had in mind for their New Central Park.

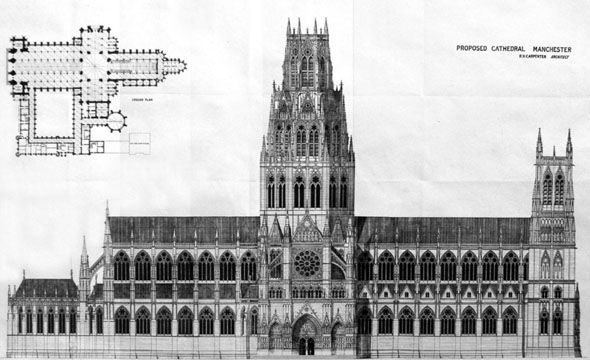

The idea for an Art Gallery or a Cathedral was nothing new as a focal point for the northern end of the city centre. A few years before the publication of the book there had been a competition for an art gallery in Piccadilly and in the late nineteenth century a plan for a cathedral there had been a strong contender. Neither had worked out so as the debate raged on a temporary 'gardens' was installed which has become a millstone around the city's neck and also an excuse not to go for a proper city centre park.

Curiously, almost exactly where an 'exhibition centre' was suggested at the southern end of the 'central road', arts centre, HOME, has recently risen, although the small square it sits within is hardly the introduction to eighty acres of noble landscaping.

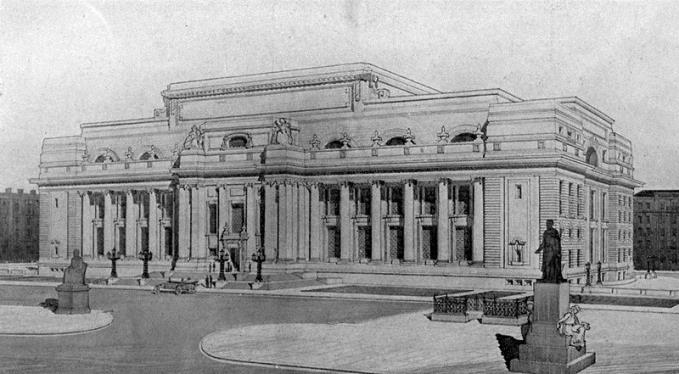

One of the ideas for a Piccadilly Art Gallery, you can see the still present Queen Victoria statue on the left foreground

One of the ideas for a Piccadilly Art Gallery, you can see the still present Queen Victoria statue on the left foreground

The monumental plan for a new Manchester Cathedral in Piccadilly from the nineteenth century

The monumental plan for a new Manchester Cathedral in Piccadilly from the nineteenth centurySimon, Inman and Tetlow's proposal for the 'central road' anticipates elements of the 1945 Manchester Plan and almost certainly inspired some of the ideas proposed in that brutal re-imagining of Manchester (the plan is discussed within this article). The Manchester Plan would have destroyed more than ninety per cent of the city's pre-1914 architecture and imposed a grim gridiron of streets.

But in the 1930s, before World War II, before the post-war ascendency of the town planner, before the decline in the relative status of the city, the dreams are far more human and humane, despite the city and country being in the grip of an international depression and with the dark spectre of Facism haunting central and southern Europe. The map above shows how St Peter's Square was also to be expanded to spread south-east as far as George Street at least. There are even traffic calming measures in these plans. It's a lovely vision.

The Rebuilding of Manchester holds a mirror to the modern city and reveals across 81 years that the problems and hopes we have for our city centre are reflected in stark clarity. The Manchester Guardian, as it was before it became the Guardian, hired the celebrated Professor Patrick Abercrombie to review the book. 'This is indeed a book to make Manchester think,' wrote Abercrombie on June 24, 1935, 'and it shows how Manchester can again lead the country.'

In terms of a coherent large green space in the city centre, Manchester is still waiting for that leadership. An opportunity to buy the former BBC site on Oxford Road has been lost, which would have delivered a five or six acre riverside garden in a very busy part of the city centre. Through much of the last hundred and fifty years Manchester would buy city centre areas to make improvements, those days it seems are past. The city might oil the wheels for developers to construct more buildings but it won't create that proper city centre park.

Of course such criticism must be tempered with reality. In 1935 the levels of pollution, the smog, the dereliction and poverty in what we consider the city centre would make our jaws drop with a clang. The energy of an industrial city centre might be exciting but the industrial grime would repel us. Still the fact the latter no longer exists in its worst forms shouldn't stop us making reasoned appeals to push the progress of the city centre further. The ideas contained in The Rebuilding of Manchester still carry weight.

This article comes from Jonathan Schofield's follow-up book to Lost & Imagined Manchester, which will be published in May. You can buy the first book here which contains detailed descriptions of the Piccadilly Cathedral and Art Gallery proposals.