Jonathan Schofield recalls a striking failure and other Mancunian sculptural controversies

London Bridge is falling down - so goes the nursery rhyme. This week London’s Garden Bridge, designed by ex-Manchester Metropolitan University student Tom Heatherwick, did fall down. But only conceptually, the hugely expensive project, scrapped due to spiralling costs and concern over its value, didn’t actually come crashing to the street.

Though Tom Heatherwick’s major Manchester work did just that.

His towering, 56m (184ft) sculpture, B of the Bang, had one of the shortest life spans of any major global artwork. It was erected in 2005 and dismantled in 2009, lasting less than a tenth of the time of, say, the equally ambitious sculpture, the Colossus of Rhodes.

Now, some might think to compare Heatherwick’s airy porcupine with one of the Seven Wonders is perverse, yet the work had a vigour, an elegance and a truly exciting sense of scale.

Unfortunately, the tip of one shook off and narrowly avoided impaling a double-decker bus

The statue was located in Sportcity, two miles to the east of the city centre and cheek by jowl with the City of Manchester stadium (now Etihad Stadium). It was easiest the tallest sculpture in the UK and probably the heaviest at 160 tonnes. It leaned at an angle ten times more acute than the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

The work was commissioned to commemorate the 2002 Commonwealth Games, the name inspired by the words of British 100m world champion, Linford Christie, who said he'd break from the starting blocks at the ‘b of the bang’ of the starting pistol. The sculpture was supposed to be in place by 2003. That never happened. So delays in construction inspired the local nickname ‘G of the Bang’.

For the short while it was around it was thrilling to stand close to the sculpture and watch the spikes shake in the wind. Unfortunately, the tip of one shook off and narrowly avoided impaling a double-decker bus. Opinion was divided on the causes, either the sculpture was so experimental that techniques to keep it safe had yet to be invented, or the engineering was a rank failure.

Eventually, after many attempts at remedial work, the City Council sued the contractors and the artist and received £1.7m in compensation for a work which initially cost £1.42m. The central core was eventually sold for a scrap value of under £18,000. There’s a rumour the 180 spikes remain in storage.

It would be harsh to judge Heatherwick a failure as a designer however. That two major schemes have not stood the test of time tells only part of the story. His Rolling Bridge in Paddington Basin shows pushing the envelope in civil engineering doesn’t always end in failure, as did his Olympic Cauldron for the 2012 Games and his design for London Routemaster buses.

Several other Manchester attempts at progressive sculpture have fallen out of fashion, if not literally fallen to bits as with B of the Bang.

Vigilance by Keith Godwin from 1971, located outside the former Manchester Evening News offices off Deansgate, lasted until 2003. This abstract work stood 5.5 metres (18 ft) in steel on a red granite aggregate base. Never popular, it was placed into storage when the Spinningfields development moved on site and nobody has heard of it since. The same happened with The Little Prince by Jane Ackroyd, a crazy mess of a work located outside Market Street which, whilst being unveiled in 1985 by the Lord Mayor, was critically judged by a passer-by who bellowed: “Bloody hell, that is really s****.” It was, and so only lasted until 1993, a rusting blight on the area.

Then again, not even the most distinguished of city monuments have always been admired. The Albert Memorial in Albert Square dates from 1867 and was designed by Thomas Worthington. Under the spire of the memorial is a statue of Prince Albert by Matthew Noble. The memorial, which predates Gilbert Scott’s in London’s Hyde Park, is swathed in heraldry and sculptured details include Art, holding a pen and scroll; Commerce, resting upon a ship’s prow, and other idealised representations of the subjects that had interested Albert.

By the sixties it wasn’t always admired and even appeared on a list of the world’s ugliest objects.

Some in Manchester agreed and in 1968 Councillor MJ Taylor objecting to the cost of £22,000 to clean and restore it, moved a council motion to violently demolish Queen Victoria’s beloved husband. “I think the Memorial is a disgrace,” he said, “and most people I asked about it were in favour of dealing with it with a stick of dynamite.” One suggestion for poor old Albert was that the resulting shattered stonework should be used as ballast for the motorways around Manchester. Fortunately Albert survives having escaped dynamiting and his own ‘b of the bang.’

Meanwhile, some of the Prince’s neighbours in Albert Square could have had a complete makeover if a scheme by artist Liam Curtin, reported here in Confidential, had been adopted by the city in 2014.

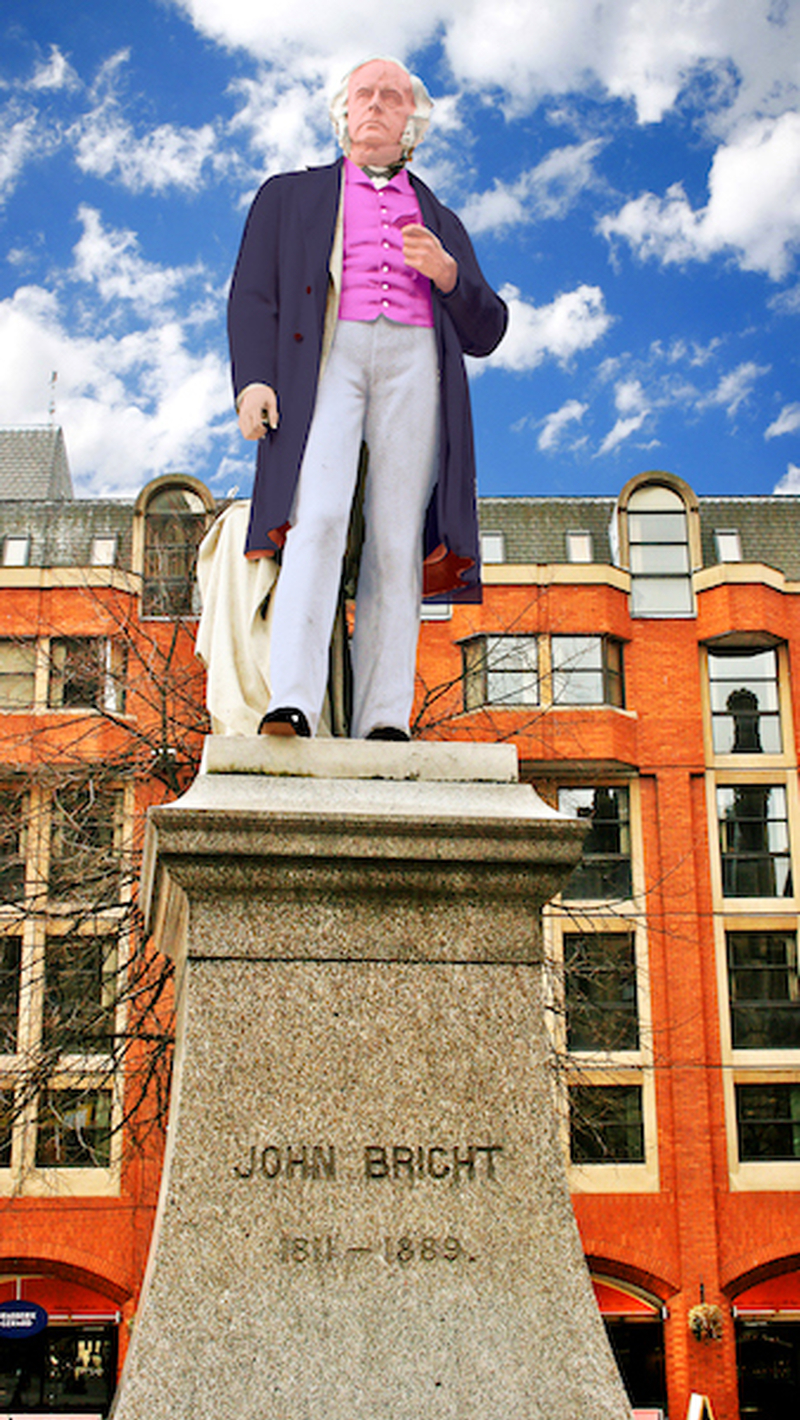

"The figures on plinths in our city squares are like forgotten ornaments on a mantelpiece,” he said. “Who was John Bright, Oliver Heywood or James Fraser, just three of the statues which decorate Albert Square in Manchester? What is clear is they were honoured by the public at the time and thought to be of great importance to the city, special enough to have statues erected to celebrate their lives. I propose we paint each statue, faithfully rendering it in colour with the advice of costume historians. Tours, web links and other materials will then explain the person, his statue and the reason for this life being celebrated."

This superb idea is yet to be taken up by the city authorities but would certainly add lustre and interest to the oft-forgotten dead of the city.

To brighten up Manchester was something much discussed at the beginning of the twentieth century. A visiting academic, John Currie, wrote to Mancunian newspapers with his thoughts in 1910. He liked very much the architecture and the energy of the city but decided the statues were dull and the city streets needed more colour. In response the Daily Dispatch came up with some suggestions. These included policemen with ribbons on their helmets and carrying posies of flowers, trams with roof gardens, factory chimneys adorned with branches from trees and ‘street corner loafers’ costumed in fancy dress.

For God’s sake people don’t tell Councillor Pat Karney about these ideas.