No philosophical background? No matter. If you're asking questions, you're in

Sometimes the word “philosophy” can get confused with “having a philosophy”. One is a distinguished if somewhat dry academic subject practised by men with beards in book-lined libraries (so the stereotype goes), the other boils down to Instagram motivational quotes, moonbathing your crystals and tapping into other people’s energy.

There has to be a healthy middle way that isn’t total woo or totally inaccessible. A way for people to think about how to live their lives with meaning, how to treat other people, good versus evil, and how to live, love, laugh (whoops sorry, how did that inspirational quote get in there?).

But any decent philosophical investigation starts out by defining its key terms. So, what the flipping heck is philosophy? If they aren’t stroking their beards or popping jade eggs up their yonis, then what exactly do philosophers do all day? Luckily, the group I decided to visit were scheduled to be discussing that very question.

The Manchester Armchair Philosophers group meets up once a month in the Lloyds pub in Chorlton for “an adventure into our minds, debating philosophical ideas or whatever takes our fancy”.

The vast majority of philosophers are white, middle class and male, and that’s a problem that we all need to be trying to address.”

I wasn’t sure what to expect, but in the end the couple of hours spent in friendly debate managed to get through a heck of a lot of material. The meet-up was attended by a range of ages, and was split roughly evenly between the sexes. Our group started off by comparing science and philosophy (this wasn’t the suggested order of questions. but luckily us philosophers like to step outside the suggested order). Is, as Stephen Hawking has said, philosophy dead? Perhaps not surprisingly, a room full of people interested in philosophy don’t agree with the eminent scientist one bit and a lively discussion ensued.

As opinionated and incisive as the group are, the majority have not studied philosophy at school or university. They are all largely self-taught in this area and feel that though the classics are more or less accessible, modern academic philosophy is nigh on impenetrable, and the suspicion is that this is deliberately so.

Afterwards I asked Professor Helen Beebee at the University of Manchester what she thought of people feeling that philosophy is not for them. She told me: “A lot of contemporary philosophy is not — and is not intended to be — accessible to the layperson. But the same is true of most — if not all — academic subjects. Ordinary English wasn’t designed to cope with the kinds of concepts you need in order to do serious philosophy — but again, the same goes for, say, physics or biology. And if you’re talking to a bunch of people who are familiar with the terminology, of course you aren’t going to bother defining your terms every time.

“On the other hand, I do think it’s important for us to find ways of engaging the general public; philosophy has the potential to be a life-enhancing thing for everyone, not just the tiny minority who get to study it formally at school or college. At the University of Manchester we have an annual public lecture, and I think so far these have succeeded in being accessible and engaging for people with no philosophical background. We also had a really nice event a couple of years ago on the relationship between philosophy and the sciences — we had a neuroscientist, a biologist and a physicist as well as several philosophers. We’re also doing an increasing amount of outreach work with local schools and colleges. The vast majority of philosophers are white, middle class and male, and that’s a problem that we all need to be trying to address.”

The Manchester Salon is another keen hub of thought that is trying to attract a wider audience to the art of thinking, with a focus on current affairs and the morally tendentious issues of the day. The discussions are organised monthly and recent talks have included “Transgressions in Sex” and “Humans Playing God”. The organisers were inspired by the Battle of Ideas, a yearly festival of talks and debate organised by the Institute of Ideas that takes place in October. This year Manchester Salon will host a Battle of Ideas satellite event featuring experts on the alt-right, online activism and identity politics at Texture, a new venue which often hosts TED-X-style talks.

A round-up of the philosophical groups of Manchester would not be complete with mention of The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, which is the first and oldest Literary and Philosophical Society in the world, and the second oldest Learned Society in the UK. Much of John Dalton’s original research was done in a laboratory at the Society’s George Street House. The present-day Society holds talk once or twice a month on a range of subjects, occasionally of a philosophical nature. It seems very fitting (and supremely civilised) that members and their guests are invited for supper after all that intellectual graft.

Back with my armchair philosophers, there has been no supper but a couple of rum and cokes and I’ve started feeling a little bit less shy about joining in. Perhaps my favourite moment of the evening is when one member of the group opines “if you are asking the questions, then you are a philosopher.” This rather lovely sentiment comes out of an acknowledgment that philosophy is all about questions – difficult questions maybe but if they were easy then you probably aren’t doing it right.

Where to philosophise in Manchester:

The pub

Philosophy requires (gentle) disagreement and where better to gain confidence in your own opinions than the pub? Go for classic boozers such as the Lass ‘o Gowrie or Kings Arms and set the world to rights.

The library

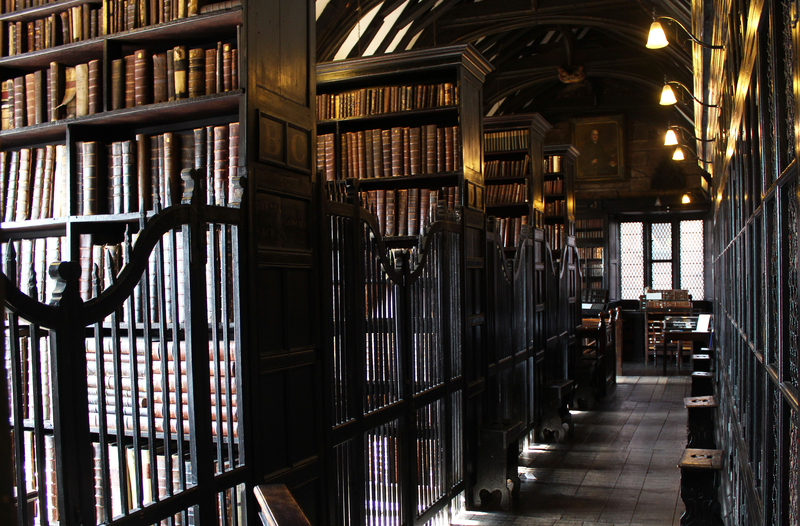

Strictly speaking philosophy needs nothing but a philosopher, however setting the ambience correctly can’t hurt. We have some beautiful libraries in Manchester, with the Portico, John Rylands and of course Chethams, really working that dusty, leather-bound magic.

Manchester Art Gallery

Manchester Art Gallery holds a bi-monthly informal discussion session called the Philosophy Café. Each session starts with looking at a piece of art linked to the topic. Absolutely everyone is welcome; the only requirement is a willingness to be open and friendly toward others’ points of view.

A cafe

If you are not feeling philosophy in the pub then go for a coffee while musing over the existential conundrum that is life. If it was good enough for de Beauvoir and Sartre then it is good enough for you. Try Icelandic coffeehouse Takk in the Northern Quarter (a second branch will soon open near the universities - handy) or neo-gothic architecture of the Sculpture Gallery (home to busts of Manchester Liberals Richard Cobden and John Bright) might inspire some intellectual flights.

The cinema

A surprise entry to the list – many films (especially sci-fi) start from a philosophical core: think Blade Runner, Matrix, Being John Malkovich, The Truman Show and many more are inspired by the questions that motivate philosophers every day. You'll find many a beard stroker in Manchester's new arts and film centre, HOME.

Online

Join the Philosophy in the North West facebook group for news of conferences and lectures in the north west.

Manchester itself is given to philosophy of a more practical nature. The Manchester School, also known as Manchester Liberalism, is a name for many strands of thought in the nineteenth century that opposed slavery, war, imperialism and advocated for free trade.

The city’s philosophical sons include WS Jevons, a logician and economist, and Samuel Alexander, a metaphysician, who worked in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which is relatively hip and happening by philosophical standards. These groovers are not well-known outside of the academy, however Manchester students will be familiar with their names at least as they turn up to lectures in buildings named after them.

More headline-catching contributions have been in the area of political philosophy (which by the standards of other kinds of philosophy is so practical it’s like being able to rewire a house while stitching on a button). Probably the most well-known example is that of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Engels lived in Manchester on and off for almost 30 years and in 1844 published his influential work The Condition of the Working Class in England based on his observation of Manchester slums. This in turn inspired Karl Marx, who was a frequent visitor, to write his Communist Manifesto. In the summer of 1845 he and Engels would study together at the table in the alcove of the Reading Room in Chetham’s Library. You can now visit the desk to pay your respects/regret the course of history and perhaps be inspired to write your own political manifesto.

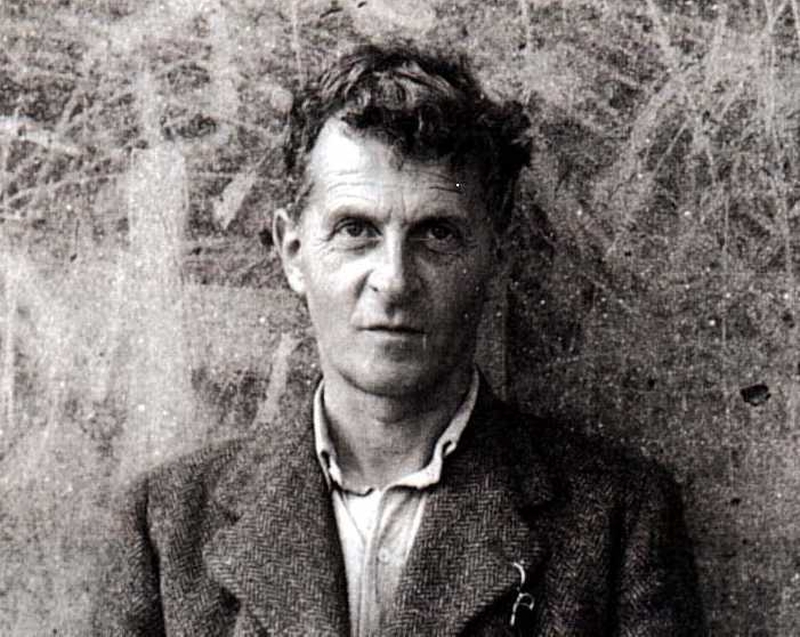

Ranked as the most influential philosopher of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein studied at the University of Manchester, though he soon jumped ship to Cambridge. Despite being one of the most rarefied and conceptual thinkers, he also showed a practical turn of mind as he was actually an aeronautical engineer during his time up north.

The exception to the trend for philosophising about matters of an earthly nature is John Dee, an Elizabethan philosopher, mathematician and occultist who believed he had spoken to an angel. In 1595 Dee was appointed Warden of the Collegiate Church of Manchester where he remained until his death.

A more recent notable student of philosophy at the University of Manchester was Milo Yiannopoulos, best known for his role in 'Gamergate' and his work at the notorious alt-right website Breitbart. He didn’t graduate.