David Adamson talks with Mines Advisory Group CEO Darren Cormack about the organisation’s work in Ukraine and beyond

Three floors above Peter Street in a modern but modest office sits the Mines Advisory Group, the most unassuming of Nobel Peace Prize recipients.

MAG - as they are otherwise known - were one of several organisations in the International Campaign to Ban Landmines that jointly received the prize in 1997.

And while the scourge of landmines has continued to march across parts of the world, from those long undetected to ones laid just last week, MAG has never been far behind.

This job does expose you to the horrors of humanity but it also exposes you to much of the beauty of the world

Although the organisation was established in what seems like another world - the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan - CEO Darren Cormack explained how just as modern conflicts have grown more multifaceted, so has their response to it.

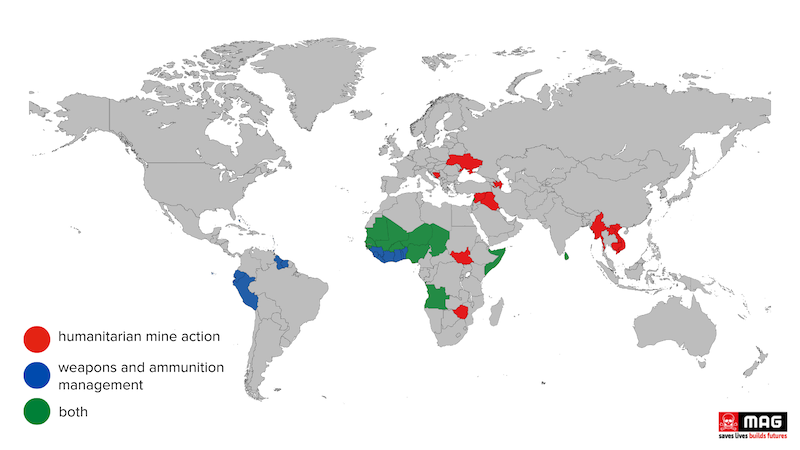

“Historically we're associated with the landmine issue,” he said. “We were founded in 1989 after seeing the humanitarian impact that the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan was having, which left a deadly legacy of landmines and unexploded bombs. We then saw those same needs in many countries that had been at conflict or were still in it, and sadly conflict remains current and on the rise globally.

“The other part of what we do is try to prevent conflict as well, and we do that in two principal ways. One is working with states to prevent the diversion of weapons that they don't hold securely enough, which can get lost, diverted, stolen and go into fuelling crime, narco-trafficking or give people the means to conduct conflict.

“Then there's also the issue of poorly secured ammunition, because many of the countries where we work were a bargaining chip within the Cold War, which left them with huge quantities of ammunition left in poorly secured buildings and store houses that were sweating under the sun and were a risk to local populations.

“So if you think what the blast in Beirut did to Lebanon in August 2020, risks like that exist all around the world and MAG conducts assessments to try and identify them and either destroy what's not needed or better manage what is there so it doesn't have the same risk of unplanned explosions.”

In the more than 30 years since its inception MAG has witnessed a bewildering shift both in how conflicts arise and how they’re conducted, but Darren places a fleet-footed and ever-evolving approach at the heart of what they do.

“Conflict is changing in some respects,” he said. “In major parts of the last century you had a sort of symmetric warfare - big state powers fighting one another, either actively or in a kind of cold war. Then we saw a fragmentation into hostility and conflict between non-state actors.

“We had the conflict in Syria, civil wars, the rise of ISIS, insurgency across the Sahel region and obviously in Afghanistan as well. So you've got very different types of conflicts involving new ideas that create new risks, like the use of improvised landmines, which has significantly increased in the last twenty years.

“Now in a way we’re back to these big state conflicts like that between Ukraine and Russia, which is almost characterised a bit like a WWI conflict with trench positions and artillery bombardment. You've got very different types of conflicts in different places, and so our work is evolving to reflect changing needs while preventing conflict as we've moved into new areas. It's about responding to the changing nature of conflict and the threats that it poses.”

While the invasion of Ukraine is at the forefront of people’s minds when it comes to conflict in the present day, Darren emphasised the importance of remembering those in need in less prominent parts of the world.

“A big focus for us is Ukraine, where we've been working since last April when we first did an assessment following the invasion,” he said. “It's a not an easy place to work, and we're currently running around an $8-10m programme there and sadly expect to be there for years, if not decades, such is a level of contamination. So within the last twelve months that's been a major focus.

“However there’s more work to do than there is the funding to do it, and aid is under pressure. There was a stretched aid budget before Ukraine, so one factor is that there's a finite amount of money and what seems like an infinite amount of work to do. So one of the tensions is trying to work out how to prioritise that, and as an organisation we've got to be responsible in terms of the size, scale and complexity of stuff we undertake.

“Funding from the UK government has reduced quite significantly in the last three years from 0.7% of Gross National Income to 0.5%, and a number of other governments are also shifting aid priorities towards Ukraine. So we've got to make sure that whilst the needs are enormous in Ukraine, we're not forgetting some of the poorest who live elsewhere in the world as well.”

One part of the world that feels a devastating local impact from a global issue is in Ecuador, where the spoils of the drug trade threaten to submerge the country, while many of the Caribbean countries contend with their own deep problems.

“I was in Ecuador last week," says Cormack, "and it's a country where there's been a 300% increase in homicide levels over the last two years due to the drug trade. 60% of those homicides include the use of firearms, and some of those can be traced back to being poorly managed in state control. So we’re working with the state to strengthen their practices and their infrastructure. Some of the ammunition I saw in Ecuador had a service date of 1890 on it, and there were homemade weapons that farmers might have used to defend their land, and many of the places where we work the weaponry is more than 50 years old. So there’s a real gamut of stuff that you can find in some of these places.

“We're just in the middle of doing assessments across ten Caribbean countries either to prevent conflicts or to help address rising levels of gun violence associated with crime. So the nature of what we do is changing, the geography of what we do is changing, and the people we need to do that work is changing as well, and all of that is relatively new in the last year or so.”

Before joining MAG in 2008 Darren worked for humanitarian aid organisations, finding himself at the centre of situations that would have seen most on the first flight back to Manchester, however he believes his experiences have only deepened his appreciation for the good in people.

“When you spend a lot of time in somewhere like Darfur in the early 2000s you are confronted with the horrors of conflict,” he said. “You meet warlords who are directly responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people, and you have cups of tea with those warlords in an effort to afford you access to areas they control so you can help those people who are most in need. So I definitely spent time sitting down face to face with people who might very well be on the International Criminal Court's ‘Most Wanted List’.

“I was caught in a very bad ambush coming back from a feeding station on the Chad-Sudan border in 2005, where we were abducted and people were very badly treated. That was a point where I think my mum's enthusiasm for what I do definitely waned, when she got the phone call saying ‘Your son's unaccounted for in Sudan’. I’ve definitely had difficult experiences as an aid worker, but that gives me the experience of knowing what I'm asking people to do in this organisation.

“There’s no question that this job exposes you to the horrors of humanity, but it also exposes you to much of the beauty of the world and in many of the places you go to you’re struck by the humility and selflessness of the cultures in which we work. Sadly it is always the extremes that disrupt it for the majority, and I think that's fair to say of most conflicts, but within a lot of that horror there are wonderfully generous people."

In early May the Pride of Manchester Awards presented MAG with the Outstanding Contribution award, and if not quite the Nobel Peace Prize, it's part of a lineage of Mancunian forces for global good.

Darren remains as modest as the office around him. “I think we quietly get on with it rather than being a vocal part of the city,” he said. “But ultimately whenever I travel I like to remind people of just how much Manchester has changed the world. In that respect I'm very proud to remind people of the roots this organisation comes from."

He pauses before adding with a smile, "But mostly people just want to talk about City and United.”

Read next - Black cabs and their cash-only obsession

Read again - Beveley Craig, Manchester council leader, what are her ideas?

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!