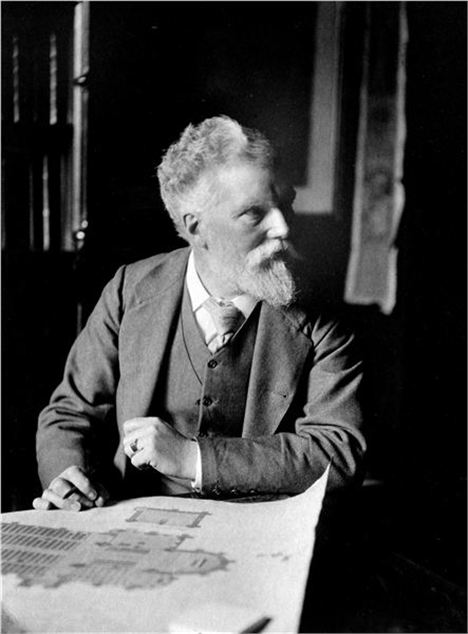

The Architect - Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905)

Waterhouse was the perfect Victorian both through his principles but also in the coincidence of his life span which almost exactly matched the duration of Queen Victoria’s reign (1837-1901). Born in Liverpool, he studied architecture in Manchester under fellow Quaker, Richard Lane. After setting up a practice in 1853, his first big success came in 1859 (he was just 29) when he won the competition for the huge new Assize Courts in Manchester. There was no holding him back after that.

In Manchester he built major buildings such as the Town Hall, Strangeways Prison and the main University block, in London he designed the Natural History Museum. The nation is stamped with Waterhouse buildings. His last phase designing hot red terracotta buildings for the Prudential Assurance Society didn’t flatter him as the style resulted in the nick-name Slaughterhouse Waterhouse. He was President of the Royal Society of British Architects from 1888-91, and was a kindly man, married twice, fathering 12 children.

The Inventor – George Garrett (1852-1892)

The remarkable Reverend George William Garrett wasn’t a natural clergyman. Born in Moss Side, Manchester, he caught the inventing bug when his father sent him to Owen’s College, later Manchester University. After university he persuaded financiers to back his submarine project with £10,000. He had a 33 ton, steam-powered, submarine made at Birkenhead. He set sail for Portsmouth to claim the £60,000 prize the Royal Navy promised if his project worked. The air filtration systems failed and the sub surfaced at Rhyl. Garrett hired a steam yacht hoping to be towed to just off Portsmouth where he’d submerge and re-emerge in triumph. But the yacht broke down, the crew of the submarine went to fix it and the last man out left the hatch open, the submarine sank. A lifeboat came to rescue the crew, rammed the yacht and sank it. The name of the submarine was Resurgam, Latin for ‘I shall rise again’. It never has.

Garrett left the church and in pursuit of his submarine dreams travelled to Sweden, served with the Ottoman Navy, then failed at farming in Florida and became a US Army corporal. He died of tuberculosis in New York. His father, the vicar of Christ Church, Moss Side, died equally unfortunately; in the pulpit delivering a sermon on the danger of sudden death.

The Suffragette - Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928)

Emmeline Goulden’s mother and father were both radical in their beliefs, although this hadn’t prevented the father surveying his sleeping daughter one night and muttering sadly, “What a pity she wasn’t born a lad.” Still, Emmeline inherited her parent’s radicalism and later married Manchester lawyer, Richard Pankhurst, a committed socialist. Richard died suddenly in 1898.

Emmeline, a member of the Independent Labour Party, carried on, becoming the Registrar of Births and Deaths at Rusholme to support herself and four children. In 1903, frustrated by the lack of constitutional progress made by the existing female suffrage movement, which had been led by another remarkable Mancunian, Lydia Becker, she set up the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in her home on Nelson Street. After raising the banner of ‘Votes for Women’ in Manchester in 1905 the movement became militant. “That is the whole history of politics,” said Pankhurst. “You have to make more noise than anybody else, you have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else, in fact you have to be there all the time and see that they do not snow you under.”

There is some debate whether the violent tactics advanced the cause or put it back but, delayed by war, women over 30 got the vote in 1918. Women, over 21, gained the franchise in 1928 – giving them equality with men in this regard. By 1928 Emmeline had done a political U-turn and was standing as a Conservative Party candidate.

The Mathematical Politician: Dame Kathleen Mary Ollerenshaw, (1 October 1912 – 10 August 2014)

Ollerenshaw was born into the wealthy Timpson family of shoe shops and shoe repair fame. Her childhood was made complicated by her hearing problems which left her deaf by the age eight, although her hearing was partially regained with a hearing aid in her late thirties. A pioneering University of Manchester programme taught her lip-reading and she started to thrive at school not only in mathematics ("The one school subject not dependent on hearing," she said), but in sport as well, playing hockey for the North of England. Later in life she became a celebrated University of Manchester lecturer on mathematics, in which she had a special fascination with magic squares, grids in which the numbers add up horizontally, vertically and diagonally to the same total. She also became a well-known educationalist, committed to improving standards within the education system.

At the same time she represented the Manchester council ward of Rusholme as a Conservative councillor. She was Lord Mayor in 1975 and moved into the Town Hall's Lord Mayor's quarters, writing a children's book The Lord Mayor's Party in 1976. Part of her young life was spent in boarding school, where she developed a learning technique called 'subliminal learning':

"Before falling asleep, I 'drew' with my finger any relevant geometrical figure or algebraic equation on the partitioning of the bedside wall. The result would be miraculous. Without fail, on waking in the morning, the details, the logical argument required or the facts that I needed to recall were clearly imprinted in my mind and, because of clarity, any required solution would often be clearly 'written' on the partition."

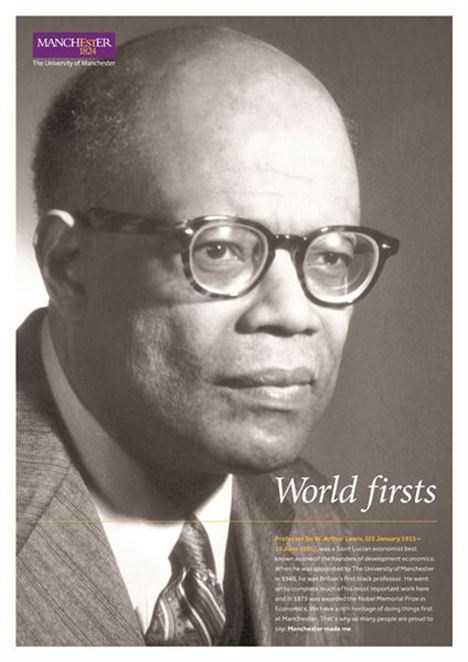

The Economist - Sir Arthur Lewis (1915-1991)

Lewis was the first black Nobel Prize winner in an academic category, indeed the first black winner in any category other than peace. He was from the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia, but studied and taught at the London School of Economics. However, it was in Manchester from 1948 to 1957, as the first black professor in the UK, where he made his major contributions to development and growth economics leading to the 1979 Nobel Prize.

In essence, he placed ‘development in a historical context, stressing the transfer of labour from the traditional agricultural sector to the more productive industrial sector’. In his view development was not an isolated exercise but one in which political, social and cultural influences were crucial. This became known as the ‘Lewis Model’. He also believed further education was key to progress. With his prestigious colleague Max Gluckman, Professor of Social Anthropology, he set up two social and educational centres for Manchester’s Afro-Caribbean population. After Manchester he led the University College of the West Indies, later working at Princeton in the States. He has a building named after him within the University of Manchester campus.

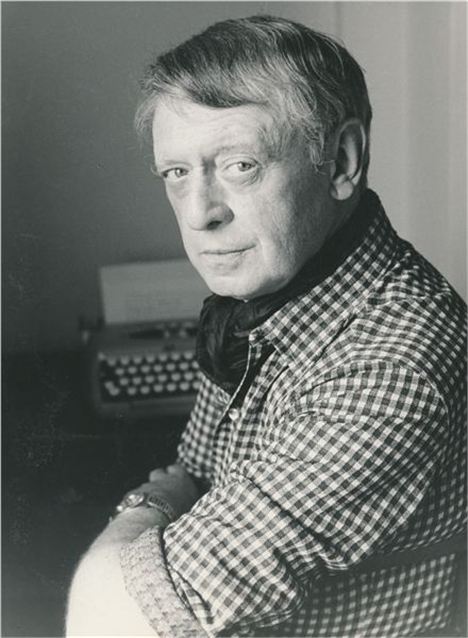

The Polymath – Anthony Burgess (1917-1993)

One brief biog of deceased Manchester author Anthony Burgess reads ‘English author, poet, playwright, composer, linguist, translator and critic’. It might also have added, ‘drinker, smoker, periodic curmudgeon, conversationalist and general good egg.’ Born in Harpurhey, Manchester, as John Burgess Wilson, he changed his writer’s name to Anthony Burgess using his confirmation name and his mother’s surname. As for his other parent, Burgess claimed he was ‘a mostly absent drunk who called himself a father’.

He became a novelist while teaching in the then British colony of Burma. He is remembered principally for A Clockwork Orange, the bleak but powerful view of a brutal future, adapted into a Stanley Kubrick film in 1971. Other works, such as those in the Enderby Series are better novels. For insight into Manchester in the first half of the 20th century, the novel Any Old Iron and wonderfully entertaining autobiography, Big God, Little Wilson, are recommended. His first wife Lynne, died of cirrhosis. Burgess’s second wife, an Italian translator, Liliana Macellari, created the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, financing it through Burgess’ estate, after the polymath's death. Burgess was a bon viveur and created his own cocktail called Hangman’s Blood: ‘Into a pint glass,’ he wrote, ‘pour double measures of gin, whisky, rum, port, brandy, add a small bottle of stout, top with champagne. It tastes very smooth and induces a somewhat metaphysical elation’.

The Impresario - Anthony Wilson (1950-2007)

Anthony ‘Tony’ Wilson's urbane confidence, fierce wit and sharp humour imbued the city, or at least the people he encountered, with a metropolitan confidence. He was a broadcaster, impresario, writer and the owner of Factory Records, the archetypal post-punk ‘indie’ label. With bands such as Joy Division/New Order, Happy Mondays and others he was the music critic’s darling. When the Hacienda nightclub opened in 1982, the legend of both Factory and Wilson was enhanced. By aiming for excellence Wilson was instrumental in reconstructing the identity of Manchester, during a difficult time of industrial decline. The city would probably not have gained Manchester International Festival without the example he set.

The richness and complexity of his character has led to his portrayal in movies. Manchester actor and comedian Steve Coogan played him in Michael Winterbottom’s 2002 film, 24 House Party People, and Craig Parkinson played him in Anton Corbijn’s 2007 film Control. After his early death to cancer, Phil Griffin, writing on Manchester Confidential, said: ‘Tony strode down Deansgate and Quay Street a Made Man. Nobody ever took Manchester this way: took it and made it better.’ There will be a street named after him in the First Street development close to the site of Factory Records' Hacienda nightclub.