Jonathan Schofield takes a starter for five with some odd and unique buildings

Architecture, buildings, man made artefacts; they come in all sorts of shapes and sizes around Manchester. Some of these are peculiar, strange and eccentric, others are simply unique. All are, in their own way, interesting.

Here we begin an occasional series looking at five very different yet fascinating curios.

Tunnel entrance to the Guardian Telephone Exchange - George Street

Public access to this sinister structure is denied...

This is one of the ugliest buildings in Manchester and one of the grimmest by association. On George Street, between Princess Street and Oxford Street, is something that looks like a WWII prisoner of war block. That mood is strengthened by the forbidding walls and gate festooned with barbed wire.

The building is the entrance to the Hades that is the Guardian Telephone Exchange. This was built in the 1950s by the Ministry of Public Building and Works, as part of a network of four tunnel complexes in London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow designed to maintain links with the rest of NATO should the UK be attacked by Soviet atomic weapons. These tunnels were not, therefore, for Manchester’s great and good (they would have had to burn with the rest of us), but for communications staff.

Soon after completion the Guardian Exchange was obsolete. Atomic weapons had given way to nuclear weapons and the tunnels weren’t deep enough to withstand that upgraded breath of hell.

Public access to this sinister structure is denied as BT currently runs cabling through them. This is a shame because in these days of returning uncertainty and a possible resumption of the Cold War, trips down there might concentrate minds and provide food for thought.

The generators, entitled Marilyn (Monroe) and Jane (Russell) after the stars of the day, still sit almost 60m (200ft) beneath the city. The vast, 35 ton steel door at the foot of the lift down to the complex contains a gun slot for shooting anybody who shouldn’t be getting in. If the worst had happened back in the fifties, and that door had swung shut with you on the inside, then you’d know you were safe for a while in this city centre bolt hole... but you’d also be aware that your family and friends were being incinerated above.

Heaton Park Pumping Station - Heywood Road

The delight on this structure belongs all to Mitzi Cunliffe... the New York sculpture best known for designing the gold Bafta mask

It looks at first site like a stumpy pylon from Ancient Egypt, a very different type of pylon than the ones that carry electricity, of course. But get up close and you find one of the great British public artworks.

The building dates from 1955 and was the handiwork of city engineers led by Alan Atkinson and the prolific city architect LC Howitt. Its task was to control the waters refreshing the city from Haweswater - 82 miles away in the Lake District. The aqueduct was completed in the 1930s, forty years after the aqueduct from Thirlmere (also in the Lake District). These were the days (as seen below with the Ship Canal) when Manchester Corporation, as it was then known, had the muscle and money to deliver epic engineering.

The delight on this structure belongs all to Mitzi Cunliffe (1918-2006), the New York sculptor who settled in Didsbury after marrying historian and Manchester University prof Marcus Cuncliffe. Cunliffe is perhaps best known for designing the gold mask presented at the Baftas. But compared to Heaton Park, that is a minor, if instantly recognisable work.

Maureen Ward of the Manchester Modernist Society got Cunliffe spot on with this description: ‘She epitomises the spirit of an exuberant, utopian partnership between planners, architects, artists and sculptors dedicated to rejuvenating the public realm after the chaos of the Blitz; functional yet accessible, experimental yet egalitarian, international yet rooted in everyday surroundings.’

The roadside wall of the building is coated, aptly, in Lake District slate. Cunliffe has incised a lovely relief of the aqueduct emerging from Haweswater on the left, then sweeping magnificently to the right, where lush, life-giving water flows out. There are figures of workmen pouring lead into a joint as well. Everything is delivered with magnificent clarity. It’s breath-taking. The history of the Haweswater scheme is shown in more panels underneath. The interior is just as good but not accessible to the public.

The Godlee Observatory - Sackville Street

...look to the roof from Sackville Gardens and you will see one of Manchester’s little jewels

The former Municipal School of Technology between Whitworth Street and Granby Row is now part of the University of Manchester. This terracotta wonder from 1895-1902 is by Spalding and Cross and is quite the equal of the Principal Hotel or London Road Fire Station in terms of spectacle. The radiant window at the entrance (on Sackville Street) includes a glorious ship inspired by the Manchester coat of arms in gorgeous technicolour stained glass. The whole arrangement in the foyer of glistening faience is impressive and, yes, open to the public - just push open the doors with their lovely brass Art Nouveau handles.

Behind the foyer is a stately lower hall with terracotta piers that is moody but mighty. The exterior is populated by terracotta heads of scholars and mythical monsters. While impressive the building is not unusual in itself, but look to the roof from Sackville Gardens and you will see one of Manchester’s little jewels. This is the Godlee Observatory from 1903, in a copper coat with a dome made of sealed papier mâché to ensure it is light enough to be turned to the desired point in the heavens. This is the home of the Manchester Astronomical Society.

Access to the telescope chamber is via a wrought iron spiral staircase that rises in three sharp turns. This is a beautiful piece of engineering but might give the faint-hearted vertigo. Under the dome of the observatory is the original Grubb telescope and refractor made in Dublin especially for this space. The dome of the telescope is manoeuvrable by ropes and wheels and has a cunning mechanism which allows it to follow the polar axis. It is refreshing to see technology that is clear in its function, a break for anybody whose life is ruled by the hidden mysteries of the microchip and the ‘cloud’. It is refreshing also to see the enthusiasm of the people who make up the Astronomical Society.

The name of the observatory comes from the patron and mill-owner Frances Godlee, who had factories in Swinton and a house in Wilmslow. He was obsessed with clocks and mechanisms such as telescopes. He was remarkably progressive when it came to the early adoption of technology too. He got in very early with telephones, and was awarded with the magnificent phone number of '4'. Just 4. Wonder if he ever forgot it?

Nico Ditch and Cathedral remnants - Platt Fields Park

There are many myths about the feature. One is that it was built in one night by hundreds of men...

There are some large oddities in this first part, but let’s also include a couple of smaller weirdos. Two of these can be seen together in Platt Fields Park in south Manchester.

Adjacent to Wilmslow Road and across from junction with Old Hall Lane is the sweet little Platt Chapel, originally from 1790 and built for Unitarians. Sadly this is empty at the moment. At the edge of the graveyard to the south and against the boundary wall of the park is a depression in the ground. This is a ditch that can be followed by entering the park at the gate to the left, then turning right and following the fence with Manchester High School for Girls.

The ditch might seem unimpressive but forms Greater Manchester’s largest surviving Anglo-Saxon remains. This is Nico Ditch, a five or so mile defensive earthwork that ran from Ashton-under-Lyne to Urmston in a shallow curve. There are several traces of it, with perhaps the best preserved parts in Denton golf course.

Why it was dug is unknown.

It may have indicated a boundary between two Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Northumbria and Mercia, and thus be 1,400 years old. Or it may date from a couple or more centuries later, from around AD890 and AD910, when Danish (Viking) incursions were threatening from the south. Certainly the ditch had the excavated earth dumped on its north side to form a barrier to invaders from the south. Whatever it looks like now it would have been an impressive feature after construction, four metres from ditch base to the top of the bank.

It’s around the time of the Viking invasions that the first mention of Manchester appears in history, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which relates how one of the greatest Saxon kings, Edward the Elder, retook and fortified Manchester. This may refer to the excavation of Nico Ditch.

There are many myths about the feature. One is that it was built in one night by hundreds of men, which seems incredible bordering on the ridiculous. Another is that Gorton and Reddish were named after a bloody battle between Saxons and Danes across Nico Ditch. Gorton thus means 'Gore Ton' and Reddish 'Blood Red-ditch'. These are nonsense too. It’s all a mystery, so make up your own story if you wish.

To add atmosphere to Nico Ditch in Platt Fields Park there are medieval ruins. When Manchester Cathedral’s west tower was being rebuilt and extended between 1862-68, one of the medieval windows - probably from the 1400s - was removed. This was acquired by one Mr Robinson, a wealthy merchant, as a folly and a romantic reminder of times passed. It now sits, a little forgotten and untended, in what was part of Robinson’s garden, before his house was demolished and the garden incorporated into Platt Fields Park.

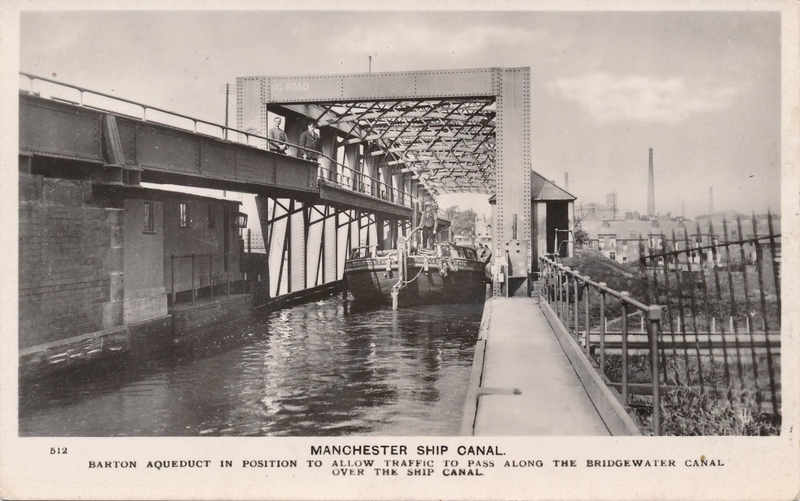

Barton Swing Aqueduct - Eccles

This is only swing aqueduct in the world... the Stonehenge of Victorian water engineering

Manchester was the British leader in delivering grand engineering projects at the end of the nineteenth century. Nothing on these islands was as big or ambitious as the creation of Manchester Ship Canal. To carve this out now would be almost as costly as HS2. What's more impressive, all the money came from Manchester. But why did we need a Ship Canal though?

In 1882, Daniel Adamson, an eminent Manchester engineer, organised a campaign for the construction of a canal to allow ocean-going traffic to sail inland as far as the city. In 1885, Parliament approved the Ship Canal Act, despite strong opposition from Liverpool Docks and the railway companies. It was these bodies which had fuelled the impulse for the canal through the tariffs they imposed on Manchester products. It had cost 19s 3d to send a ton of finished cotton from Manchester to Calcutta in 1856, of which 12s 6d was incurred getting it out of Liverpool.

It took more than 16,000 navvies six years to excavate the 56km, eight metre deep canal. Opened by Queen Victoria in 1894, the trade the canal generated, together with the large industrial area of Trafford Park which grew along the south bank, helped bolster Manchester industry for decades. At one point Manchester was the third largest port in the UK by tonnage, despite its distance from the sea.

The headwaters became redundant as container vessels grew too large. The last commercial visit to the headwaters, now Salford Quays and MediaCityUK, was in 1982 (although large ships still arrive at the grain works and scrap yard a couple of miles further down the canal).

Gargantuan engineering, mostly designed by Sir Edward Leader Williams, remains from the original construction, such as Irlam High Line Bridge. The greatest triumph and curiosity of the colossal undertaking was the Barton Swing Aqueduct. This swings 800 tons of water through the air to allow passage of ships along the Ship Canal when open, and passage of barges and narrowboats along the Bridgewater Canal when closed.

This weighty motion was controlled from a brick control tower with a steeply pitched roof, positioned in an island in the middle of the Ship Canal. The swing aqueduct rests on an axis along the island to allow ships to pass.

This is only swing aqueduct in the world and is inexplicably only Grade II* listed. It is also in a dilapidated condition, which makes me ball my fists with rage. Here is something that not only Greater Manchester but the UK should be proud of and celebrate. It is a mile from the ridiculous Trafford Centre with its millions of visitors, it is owned by Peel Group, it is unique. Why is it not a huge tourist attraction? This is the Stonehenge of Victorian water engineering and it lies forlorn and unloved.

As a postscript, Salford City Council deserve credit for creating a pocket park to the west of Barton Aqueduct which reveals part of another wonder from an earlier age. This is the retaining wall of the embankment carrying the Bridgewater Canal to the aqueduct. This is from 1761 and by Brindley and Gilbert. It carries masons marks etched in the charming red sandstone.

The swing aqueduct replaced the original aqueduct which had in its time been the wonder of its age attracting visitors from across Britain, Europe and beyond.