Jonathan Schofield bids farewell to Manchester Town Hall as it closes for a major £330m, six-year refurbishment

'We cleared a vast area, and Mr Waterhouse’s beautiful design rose, stone on stone and pillar on pillar. We spared no expense. Every detail we desired to have perfect. To have been parsimonious, to have neglected corners or recesses which were obscure, to have allowed ornamentation which was tawdry, would have been for ever to brand Manchester as a city given up to no higher thought than the quickest accumulation of wealth.'

Thus spoke Abel Heywood about the Town Hall he’d guided to completion. Heywood was a politician, printer, polymath, mayor and much, no doubt, to his posthumous delight, is now a pub in the Northern Quarter.

The designer of Manchester Town Hall was Alfred Waterhouse, acclaimed architect and much, no doubt, to his posthumous delight, is now a Wetherspoons’ pub on Princess Street.

That Heywood and Waterhouse’s ambition was to create something which wasn’t ‘tawdry’ but ‘beautiful’ was clear from the start. It was timely too. By the 1860s Manchester needed a statement building, one that reflected its world status and its role as the capital of two million people in what would now be considered Greater Manchester.

The old Town Hall from the 1820s on King Street had become far too small for what had become a city state. Manchester Corporation controlled all aspects of city administration; water, gas, police, education, parks, roads - and it was rich. A new Town Hall was desperately needed. The corporation decided it was to be ‘the equal if not superior, to any similar building in the country’.

Completed in 1877, the building is Manchester’s greatest civic structure. For many, it is a candidate for the Victorian building par excellence, the whole age summed up in one: the extravagance, the energy, the self-belief and the achievement. At the opening banquet, MP John Bright described the way the city felt about the new building: ‘With regard to this edifice, it is truly a municipal palace. Whether you look at the proportions outside or the internal decorations… there is nothing like it… in any part of Europe.’

In Albert Square, a cliff of ornate Gothic stonework drags the eyes upward to the giant clock tower above – the minute hand is 3m (10ft) in length and the spire 85m (288ft) above ground level. On the top of the spire is a golden ball with spikes symbolising a cotton bud about to burst, but also the sun, for wherever the sun shone Manchester had business. The roofline is a wonderland of pinnacles, gables, chimneys and metalwork.

The celebrations for the opening in September 1877 extended over several days, and included a procession of cavalry and infantry, police force and fire brigades, a banquet, a ball and a gathering of over 40,000 local working men with examples of their crafts.

Parts of the building had opened early in May 1877 to receive a special guest. This was Ulysses S. Grant, the eighteenth president of the USA, who came to Manchester to thank the city and region for its support in the American Civil War. Manchester had been pro-Union and anti-slavery. At the Town Hall reception Grant said:

"I was very well aware during the war...of the sentiments of the great mass of the people of Manchester towards the country to which I have the honour to belong, and of your sentiments with regard to the struggle in which it fell to my lot to take a humble part. For that, and for further expressions of the kind which took place during our great trial, there has been on the part of my countrymen a feeling of friendship towards the people of Manchester, distinct and separate from that which they feel for all the rest of England."

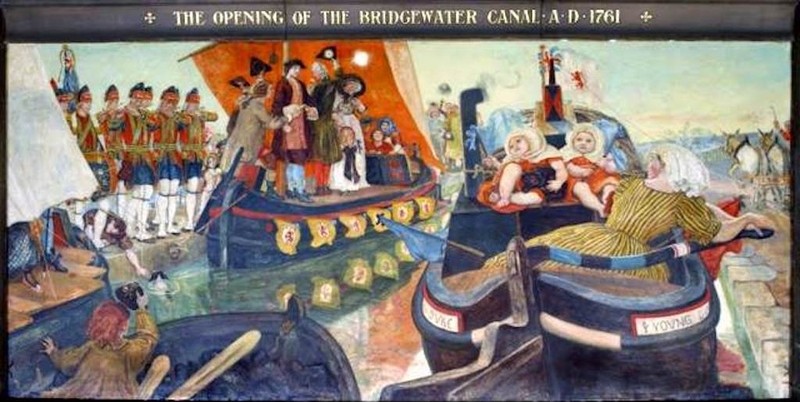

It’s the people who have populated the Town Hall that give the place life. Yes, the building has magnificent state rooms, elaborate corridors, spectacular staircases and a Great Hall with fabulous Ford Madox Brown murals depicting scenes from Manchester’s history, but they have always been the backdrop to the political and civic life of the city.

Ulysses S. Grant wasn’t the only US President to sleep over. In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson stopped over during a visit to deliver an important speech about the need for a League of Nations. Other visitors to the Town Hall include all the UK monarchs after Queen Victoria, all the UK prime ministers, plus countless sports stars, pop stars, Nobel prizewinners, artists, scientists and even astronauts such as Yuri Gagarin - the first man in space.

Let’s not forget the countless marriages in the Town Hall either, or that it became the first city hall in Europe to fly the Gay Pride rainbow flag.

The building has also been a star of stage and screen in its own right, its Gothic corridors, courtyards and chambers, appearing as a natural scene-setter for any Victorian drama. A good example being Guy Ritchie’s 2009 Sherlock Holmes, starring Robert Downey Jr, Jude Law and Rachel McAdams. It’s also been on numerous occasions the body-double for the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) as in the original House of Cards.

In the context of its 141-year history, the Town Hall’s closure for a £330m repair could be seen as simply a part of that heritage. Yet the closure will leave a six-year hole in the civic and tourist experience of Manchester. What’s galling is that if repairs had been made in a more timely fashion, then the six-year programme would have been far less. Mind you, the same goes for the Palace of Westminster refurbishment.

Perhaps the main comfort we have over the closure is evidential. The renovation and refurbishments of Manchester Art Gallery, Whitworth Art Gallery, Central Library and John Rylands Library all took years, but have all been splendid, enhancing the citizen and visitor experience. To see that level of care and skill lavished on the Town Hall, and to have it revealed almost as it was in 1877, will be a pure joy.

Let’s hope we can repeat Abel Heywood’s words at the top of this article. Manchester’s people and media will be monitoring things to make sure this is the case.

And, after all, absence makes the heart go fonder.