Jonathan Schofield continues with an over-view of the region’s architecture: this time covering the nineteenth century

For the first part of this architectural history click here.

THE nineteenth century is perhaps the century that popularly defines Manchester's architecture. This was the age of the triumph of cotton, the making of British engineering, the century where the great urban/rural population shift took place. The following description underlines the cataclysm that for better or worse utterly transformed the United Kingdom as written in the streets and buildings of our city.

By the 1850s Manchester had changed completely from the place it had been in 1800

Let's start with churches.

In the first part of the nineteenth century the fashion had returned to the Gothic style, but to begin with only as a species of Gothic dreamed up in the architects’ heads without the principles developed in medieval buildings - it was a period of time that also led to the Gothic novel such as Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. In this instance Gothic was spelt Gothick and was great fun, and is still with us in the form of Stephanie Myers and Twilight.

Charles Barry’s All Saints (1826) at Stand near Whitefield, with its tall, Gothic-horror porch, is a classic example; another is the more restrained St George's in Castlefield/Hulme by Francis Goodwin. Barry crops up again in this section and would later rebuild the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) into every tourist's favourite photo opportunity in London.

A crucial building nationally is the much messed about with St Wilfred RC (1842) in Hulme by AWN Pugin. This was one of the first ‘archaeological’ churches, harking back to the principles of the Middle Ages, if a bit dull. After it, everything with churches had to be done correctly according to the dictates of true Gothic architecture and the various accepted styles: Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular.

A selection of the best nineteenth century churches are St Mark's, Worsley (1846, GG Scott), St Mary, Hulme (now apartments, 1858, Crowther), the Holy Name, University (1871, Hansom) and St Augustine’s, Pendlebury, (1874, Bodley). This last building was considered by architectural critic, Nikolaus Pevsner, to be ‘one of the English churches of all time.’

Two curiosities are Edmund Sharpe’s church, Holy Trinity, Rusholme, (1845) built entirely out of terracotta, and J Medland Taylor’s St Edmund's in Rochdale which is as much a temple to Freemasonry as the Almighty.

But then again most things by the latter architect are a curiosity such as his St Anne’s in Denton, described as Arts and Crafts Gothic and worth a long detour to visit.

Thomas Harrison was one of the first to bring the Greek Revival to the city with the Portico Library (1806) whilst Charles Barry added the grandest of these buildings with what is now the Manchester Art Gallery. Barry’s motto for the building was 'Nihil Pulchrum Nisi Utile' – nothing beautiful unless useful, a very Manchester sentiment, much better than Peter Saville's more recent strapline 'Original Modern'.

The most individual take on this style was Charles Cockerell’s Bank of England (1845), now offices on King Street. But we have to return to Barry for one of the most inspirational buildings in the city’s history. This was the Atheneum (1837), based on Italian Renaissance palaces. With its dignified, grand appearance it was adopted by cotton barons as the style of choice for their warehouses and the so-called ‘Manchester Palazzo’ was born.

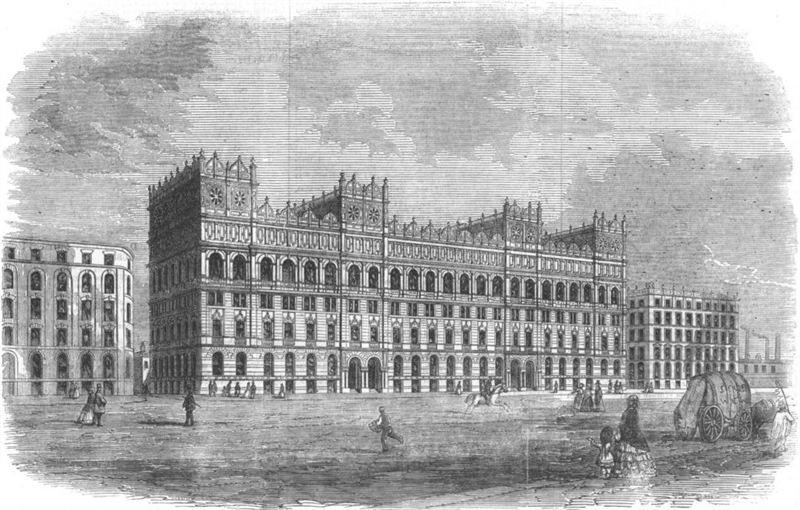

The simple but stately design of the Renaissance model allowed plenty of light into buildings whilst not wasting too much space on decoration. The main salesrooms with cotton samples were on the upper floors, the first floor provided the counting house and the administration, whilst the lower basement contained the machinery, the steam engines and the boilers. A large iron gateway led from the rear or side through which cotton carts left. The heavy carts cracked stone kerbs so iron kerbs are a feature in Manchester streets.

This picture shows one of the elegant Princess Street buildings by Clegg and Knowles, 1869. As C.R. Reilly (1924) described: ‘[the] warehouses represent the essentials of her trade, the very reason for her existence. They are too near to her heart, for any light treatment. Hence their simplicity, strength, and sincerity, and consequently their real beauty.’

Edward Walters was a fine ‘palazzo’ architect, but his best ‘palazzos’ weren’t warehouses. His masterpiece was the Free Trade Hall (1856), the main façade of which survives, in the Edwardian Hotel, whilst the Manchester and Salford Bank (1860), now the Royal Bank of Scotland, on Mosley Street isn’t far behind. Earlier JT Gregan in St Ann’s Square had built the most exquisite ‘palazzo’ of them all, Heywood’s Bank (1846), a triumph of Manchester architecture, with its attached manager’s house – the first in beautiful cut stone, the second in no-nonsense brick. Heywood's Bank is pictured in the main picture at the top of the page.

The ‘palazzo’, as with all art and architectural fashions was never a pure ideal and often was simply a frame from which to hang off a variety of designs: an essay in showmanship. This led to remarkable structures such as Travis and Magnall’s Watts Warehouse (1858), now the Britannia Hotel, the greatest of the textile warehouses occupied by a single company and a cocktail of architectural styles including Italian, French, Elizabethan and even Egyptian motifs. The present style of seedy hotel doesn't do it any favours but an idea of the ebullience of the Manchester cottontots (the nickname for the textile millionaires) is forehead slappingly in evidence in the gorgeous grand staircase.

By the 1850s Manchester had changed completely from the place it had been in 1800. Industry had already arrived by the latter date but it was still recognisably a town of the eighteenth century – it was still a product of the old ways. By 1850 Manchester could not have been confused for anywhere else, in effect it was a city state - confident of its place in the world and attempting to control its own destiny.

The change is graphically illustrated in William Wyld's 1852 painting Manchester from Kersal Moor, where the foreground shows a traditional English country scene but the background is Manchester and Salford and a world changed with the old ways burnt away in the furnace of industry.

The sense of city confidence and pride in its position was reflected in the pioneering Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, the first major temporary blockbuster art show and arguably still the biggest ever, with 16,000 works placed in an exhibition hall in Old Trafford.

The pride was also reflected in the architectural practices. Manchester begins to get dynasties of designers. The most prominent nationally was that begun by Alfred Waterhouse and continued by his sons (although Waterhouse did decamp to London). In 1859, at the age of 29, the Liverpool born, Manchester trained architect, won the commission to build the Assize Courts in the city. This essay in modern Gothic was a total success. The Courts were sadly demolished after bomb damage during WWII. It was followed by Manchester Town Hall (1877) – described as ‘a classic of its age’ - and the Victoria University (1887), now the University of Manchester, both in Gothic plus numerous other buildings.

Manchester Town Hall remains the poster-boy of the city's Victorian architecture. Or will be again when it reopens in 2025 after refurbishment.

As stated in our article on the building (Stamped and Celebrated) it is a candidate for the Victorian building par excellence – the whole age summed up in one: the extravagance, the energy, the self-belief and the achievement.

At the opening banquet in 1877, MP John Bright described the way the city felt about the new building: "With regard to this edifice, it is truly a municipal palace. Whether you look at the proportions outside or the internal decorations… there is nothing like it… in any part of Europe."

The main picture at the top of the page shows the Great Hall. You're right Mr Bright, a municipal palace indeed.

Waterhouse’s contemporary was Thomas Worthington who begun a practice which still survives in the city. His contribution straddles both buildings and monuments in a variety of Gothic styles such as the Albert Memorial (1862), the Memorial Hall (1866), and the City Police and Sessions Court (1875), Minshull Street, now Crown Courts.

The middle years of the nineteenth century have been called the Battle of the Styles in Britain, an often passionate debate between those who favoured Gothic architecture and those who favoured the Classical, and its various offshoots. In public buildings in Manchester, unlike in Liverpool, the Gothic boxed the ears of Classical.

No doubt the new money industrialists and businessmen found it warmer and more charming than the colder purities of the other style. Edward Salomans, Manchester’s most prominent Jewish architect (who had designed the Art Treasures building pictured above), must have felt the same, or at least his clients did. His best building the Reform Club (1871) is in splendid Venetian Gothic. Gothic still cast a shadow over the end of the century when Basil Champneys designed the last great flowering of Gothic in the UK with John Ryland’s Library (1900), a tour-de-force in red sandstone.

This extravagant building is a virtuoso performance in Gothic, capturing again some of the freedom and flair of the Gothick buildings of the early part of the nineteenth century within, of course, a scholarly discipline. John Rylands Library is the firework display at the end of the whole British neo-Gothic revival. It's an astonishing way to bow out.

Manchester Ship Canal had opened in 1894 and with a general upturn in business a building boom hit Manchester. The steel framed building hit the city at the same time. The buildings in the late 1890s until the outbreak of WWI in 1914 are some of the most bombastic in the city.

This was the Imperial Age, the triumph of Pax Britannica, where the sun never set on the Empire and never set on Manchester’s cotton and manufacturing interests either. For a decade after WWI the great building programme continued with buildings such as Harry S Fairhurst's Lancaster House and India House, but they will be covered in part three of this history.

For the first part of this architectural history click here.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield

If you liked this article you'll probably like...

Manchester architecture part one

Elegant city centre boost with hotel in a heritage building

Manchester airport plans

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!