Beneath the Etihad Stadium there was once a mining shaft five times the length of Beetham Tower

Where Manchester City’s gleaming Etihad Stadium presently sits was once one of the UK’s deepest pits. A shaft at Bradford Colliery reached a depth of over 870m (almost 2,900ft).

To get an idea of how deep this is, take a look at the image of Beetham Tower further down this page. Take that 169 metre tall building, slam it into the ground, then multiply that distance by five. Now you have an idea of how deep Bradford Colliery extended. One report says it could take up to fourteen minutes to descend to the depths.

Coal was first mined from the early 1600s on this site and continued to 1968. Originally the colliery was in the countryside - away from the traditional centre of Manchester - but steadily, through the nineteenth century, the city sprawled east and enveloped the workings. In its later years, the coal taken from the ground was consumed by the nearby Stuart Street Power Station, which has also disappeared.

As one of the histories notes: ‘Many Bradford miners made names for themselves in wider spheres. One of the Miners' Federation representatives who returned to the House of Commons in the 1910 General Election was John Edward Sutton, a Checkweighman at the Colliery. John Edward Sutton (23 December 1862 - 29 November 1945) was the Member of Parliament for the Manchester East Constituency from January 1910 until 1918, when the constituency was abolished. He was a trade unionist and Labour politician.

‘(Sutton) joined Bradford Colliery, aged fourteen years, where he became a Checkweighman as well as becoming Secretary of the Bradford Branch of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners' Federation. In 1894 he was elected to Manchester City Council as an Independent Labour Party Councillor for the Bradford Ward. The Lancashire and Cheshire Miners' Federation was founded in 1897 and it was wound up in 1945. Its office was in Bolton.’

Closure of the colliery in 1968 followed subsidence caused by the shafts, dug under what had become a heavily populated part of the city. Despite huge reserves of high quality anthracite coal, the costs associated with subsidence made Bradford Colliery uneconomic.

In its final year of operation there were 1,500 workers employed on the site producing 530,298 long tons (593,933 short tons) of coal. Subsequently the seven-acre (6.9 ha) site, renamed Eastlands, was cleared and its two deep shafts capped with reinforced concrete in a scheme costing £8 million.

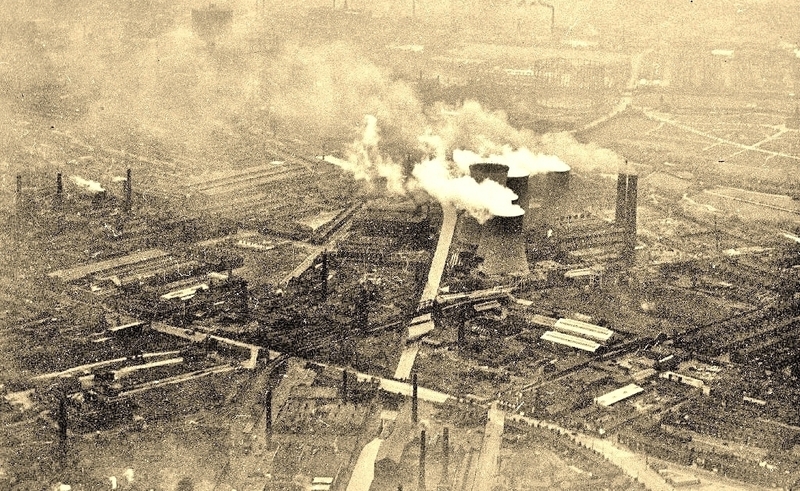

East Manchester had been one of those places dubbed the Workshop of the World in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century; a seedbed for heavy engineering, chemical works and countless other types of enterprise.

Today there is little to remind us of the energy expanded here, energy that had been partly powered by Bradford Colliery’s coal. Instead, twinkle-toed footballers on multi-million pound contracts dance over a subterranean world where thousands of men toiled for over 350 years, some of them never making it back to the surface alive.