With stalwarts such as MadLab and Marc the Printers now gone, Andrea Sandor speaks with those being pushed out of the city's indie heartland

If you live or work in the Northern Quarter, you’re probably aware of how quickly things are changing. It feels like a particularly exciting time for food and drink: Patron, Folk & Soul, Just Between Friends and Flok are just some of the new bars and eateries that have opened up in recent months.

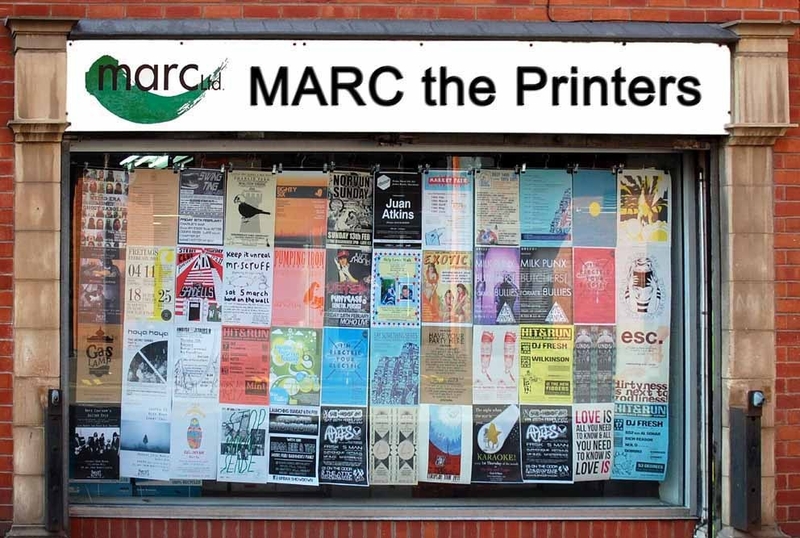

However, at an equally fast rate other organisations and businesses are moving out or shutting: MadLab, Marc the Printers, the Wonder Inn, Texture, and Bonbon are just a few of the more recent examples. If you want a lesson in capitalism, it would seem, come to the Northern Quarter.

I started taking a greater interest when MadLab, a grass-roots innovation organisation, moved to PLANT NOMA in May. I help manage a community group that meets there and received an email from a member asking what the move meant for our group. Clueless, I got in touch to find out.

MadLab’s thrilled to be partnering with PLANT, where it continues to operate as normal, but the team openly acknowledges that the move wasn’t their choice. Rather, it’s the result of what they believe are wider issues happening in the area due to “rocketing rent prices and insensitive development.” On their website, they say they’re in talks with the Arts Council, Andy Burnham and Manchester City Council about the need to protect and grow a diverse creative landscape.

You can stop reading there, because that’s essentially all I’ve been able to find out too. Except you should keep reading. Why? Shoreditch, that’s why. That should be enough to make any Mancunian vomit. Small businesses, arts and community groups are what makes a place a place. They attract people and make them want to stay. And while not a Mancunian myself (I herald from Washington D.C. a poster city for institutionalised arts), I’d like to want to stay. So my project began.

We didn’t want to move, but it was made clear to us that rent would increase by a third

Within a couple of hours of emailing her, I was on the phone with Rachael Turner, MadLab’s energetic CEO. Apart from hosting community groups, MadLab runs a range of courses, from digital skills for women to workshops on biotechnology. Located on Edge St since 2009, they had to move when their rent was put up 40%.

Rachael’s realistic and accepts the landlord’s point of view, “They have to maximise their profits and would argue they’re not in the business of community generation. I understand that viewpoint. But that doesn’t make it any easier for us.” Rachael says the skills they equip people with through MadLab’s offering feed into the economy in a wider way. “There needs to be some kind of infrastructure for small, community organisations,” she asserts.

Talking to Kirsty Almeida, who dreamt up and ran the Wonder Inn, also makes me aware of just how much demand there is for community spaces. Tuesday nights, for example, might have seen the building filled with up to seven groups, including yin restorative yoga, holistic boxing, Japanese mindfulness flower arranging, creative writing, doodling, as well as sold out university events with over 100 attendees. I didn’t know all of those groups existed, but they do and they want spaces to meet in.

While Kirsty says she’d team up with a business partner if she were to do it all again, she still believes it’s a pity she wasn’t able to access more support for an organisation that brought in so many community groups.

Community organisations aren’t the only ones moving out. Marc the Printers, a stalwart of the area for 21 years, packed their bags and have set up in Salford. “We didn’t want to move, but it was made clear to us that rent would increase by a third,” Colin tells me on the phone between greeting customers at the shop. Like Rachael, he too is realistic. “I understand there are market forces and landlords have to maximise profits for their shareholders. It’s a cycle - maybe Salford will be the new Northern Quarter.” But there’s an edge to his voice and he cynically predicts that the whole block - now that MadLab and Majolica Works have also moved out - will be demolished and replaced with high rise flats.

While Marc’s moved to Salford and Kirsty’s returned to her music career, MadLab’s still closer to “home”. At PLANT, an open design studio and workshop space that includes pottery and woodwork, members of the public can use the space, free of charge “as long as your project will make Manchester an even more interesting place to be.”

PLANT’s run by Oh OK Ltd on behalf of NOMA, a 20-acre mixed-use development scheme that aims to be a northern gateway to the city. NOMA gives PLANT the space for free, as well as a budget. I can’t wrap my head around the idea that a developer would take this approach, so I get NOMA’s brand and marketing manager Nicky Moore on the phone.

...relying on a “benevolent landlord” isn’t the most robust position to be in

Deeply passionate about NOMA, Nicky sounds surprised by my question, “PLANT is crucial for us. We’re very aware of the value of their place-making services,” she tells me. From NOMA’s perspective, PLANT is a loss leader, bringing people into the area in a plan to slowly develop the area into a genuine neighbourhood.

Ben Young, the director of Oh OK Ltd, is very enthusiastic about the partnership with NOMA. However, he acknowledges that relying on what he calls a “benevolent landlord” isn’t the most robust position to be in. Their resiliency, he says, comes from being flexible and agile, able to move quickly and set up in new premises. That said, Ben’s keen to work with the private sector and demonstrate the value of funding organisations like PLANT.

NOMA isn’t the only example of a benevolent landlord. Colin tells me that Millerbrook Properties wanted Marc to move into Upper Tib Street after Barry Electronics moved out, but unfortunately the space was too small. It’s now leased to Siop Shop, an owner-operated independent, known for their heavenly donuts (they didn’t ask me to make that plug, it’s just true).

Colin says Millerbrook are strict about the kind of enterprise they want occupying their space, and Iwan Roberts - one half of Siop Shop - agrees they have a good ethos and want to help maintain the independent character of the Northern Quarter.

However, Millerbrook have come in for bad press recently regarding developments that might push out Rocker, the rock’n’roll clothing shop that has been in the area for ten years. In a recent article, Millerbrook’s consultant Richard Ward says rents have gone up in the area and the building is badly in need of renovation. So even this example has its murkiness.

But regardless, having a benevolent landlord is great when you have one, but the trick is having one. This doesn’t seem to have worked for MadLab or Marc.

Rachael tells me she’s been in touch with the Arts Council. When I follow this up, I’m told that “one of the Arts Council’s priorities is to make the North a place where artists can settle and work - and also make a living.” They say they’re currently in conversation with Manchester City Council about workspace development for artists and cultural organisations - and as such are unable to comment on the situation in the Northern Quarter at the moment.

I get in touch with Jon-Connor Lyons, a ward Councillor for the area who’s on neighbourhood and planning committees. He reassures me “local Councillors want to ensure the Northern Quarter remains independent and unique” - but can’t say much more as he’s on the planning committee.

So things might be happening at that level... maybe? However, these limited responses don’t leave me feeling particularly encouraged.

He says it turns out they were “harbingers of gentrification”

After a week of chasing, I get Liam Curtin on the phone, who opened Majolica Works with Wendy Jones on Edge Street in 1986. He saw the area transform as small arts organisations like his moved in. Quoting Jane Jacobs, he says it turns out they were “harbingers of gentrification”.

At the time, Liam was involved with the Northern Quarter Association, which saved several derelict buildings. Then he saw small arts organisations slowly replaced by the commercial arts. While nostalgic for the past, Liam acknowledges that he’s benefited from rising property prices, having bought a building in the Northern Quarter with five others and selling it years later, effectively as a pension. They only leased the building to arts organisations and the new landlord will have to honour the 25 year leases. But the Northern Quarter Association has long dissolved, having achieved its five year plan and members moving on with their lives. The Association was a labour of love, says Liam, and didn’t necessarily pay the bills.

Liam tells me about Temple Bar, Dublin’s “cultural quarter”. Like the Northern Quarter, the area had fallen into decay and was earmarked for urban regeneration. It attracted artists and small businesses in the 1980’s due to cheap rents, which helped revitalise the area. Rents skyrocketed, smaller ventures were pushed out, and Temple Bar became a tourist magnet, reknowned for its nightlife, drawing stag and hen dos.

While Temple Bar might be a crystal ball for the Northern Quarter, an alternative narrative - for better or worse depending on your perspective - is Shoreditch. Gentrified by creative industries, the once working class neighbourhood is known for its hipster offerings at inflated prices.

“It’s the same story everywhere”, Liam concludes, “How do you contend with market forces? You would need some kind of municipal government, I suppose.”

Apart from relying on benevolent landlords, municipal government is the only solution I’ve come across during this research. Sam Wheeler, also a ward Councillor for the area (and occasional Confidential contributor), tells me, “The problem as I see it isn’t of will but of legal powers.” He strongly believes the answer is greater devolution and more ability for local Councils to craft specific policies for their wards. “I think we should have the powers over rates, our own borrowing, and the ability to use our procurement muscle to support the types of businesses we want in Manchester.”

We can accept that gentrification is inevitable, that artists will always be nomads moving from one area of a city to another until they’re priced out and move on to another city where the process starts again. We can accept that independents will only survive if they’re “strong” enough and may too follow the artists elsewhere. Or we - Manchester - can find another way.