Andy Spinoza, who was there as it happened, interviews and reviews the biography of the mercurial Manc

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Walt Whitman, Song of Myself, Leaves of Grass, 1855.

Tony Wilson denied he ever had a career. Instead, “his occupation was Manchester”, writes Paul Morley, who was chosen by the magnificent, maddening pop culture maverick as his official biographer.

Salford-born Wilson died from cancer in 2007. His 57 years were packed with provocations, infatuations, successes, tragedies and controversies. Paul Morley has, in many ways, been writing Wilson’s story his whole life.

Football gave the city profile, but Factory gave it fascination and global sex appeal

The 11-year-old Reddish boy first became excited by books and ideas in the hush of his local library. “I was trying to find a light in the darkness, opening doorways into other worlds,” he says, in defiance of being “educated to be just another number.”

Initially a kind of awestruck younger brother, then a co-conspirator, in From Manchester with Love: The Life and Opinions of Tony Wilson, Morley begins each chapter with long lists on his subject: “emotional vampire, merry prankster, playboy philosopher, financially strapped, devious auteur, gregarious loner…acid casualty, bloody-minded sensationalist, halfway to megalomania…perpetually hosting a masterclass in the art of being Tony Wilson.”

The printed word brought the bedroom publisher and TV reporter together when Wilson read Morley’s Sex Pistols article in his Out There fanzine. Both witnessed the insurrectionary punk band bring the lightning to the city in 1976. Their two incendiary Lesser Free Trade Hall gigs set off cultural bonfires across the city, sparking new bands, artists, record labels, venues, fanzines and writers.

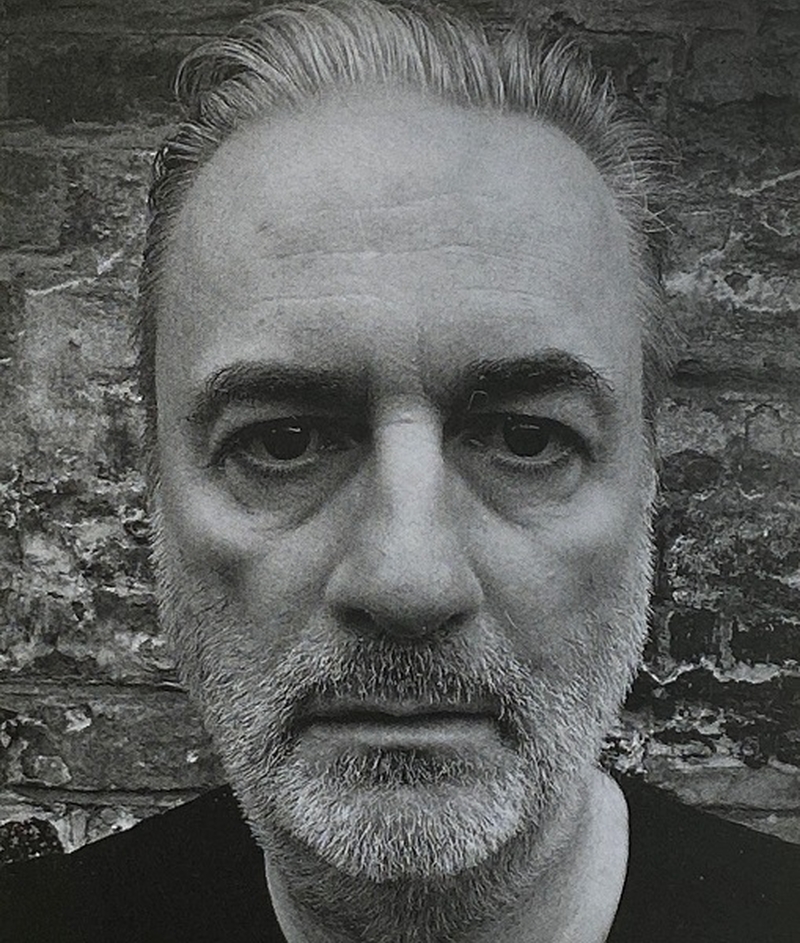

Paul Morley on 'Wilsonland'

Morley became the defining post-punk era writer. In the all-powerful New Musical Express, he all but created the Joy Division/Ian Curtis northern Gothic shaman myth. Manager Rob Gretton denied him interviews, so Morley invoked Sartre, Kafka and Beckett in 5000-word mega-features, the moody Manc existentialism intensified by Kevin Cummins’ monochrome images.

"Wilsonland", as the book’s witty map has it, not only includes the mutating city centre now bursting at the seams but the mythic Manchester that exists in the heads of people the world over. The one where Wilson is, in Morley’s words, “the metaphysical lord mayor”.

Wilson’s Factory cabinet included Gretton, designer Peter Saville, producer Martin Hannett and minister without portfolio, the actor Alan Erasmus. It may have been a boy’s club – Morley is unsparing in how women were side-lined - but they gave sustenance and space to what Wilson called “the interesting community”.

Manchester - the greatest place on the planet

Wilson had many "homes", Granada TV, Factory Records, the Hacienda club and the pimped Jag which doubled as a mobile office. As the Factory crew spliffed and riffed together through these diverse locations Wilson would apply his philosophy of "praxis" to everyday life, namely doing stuff then understanding why you did it later.

In hindsight, what Wilson and co were perhaps doing was laying the path for political devolution. Manchester (and Salford) for Wilson was the greatest place on the planet. His achievement was to inspire a city through a collective effort, firing up Mancs and incomers to forge a new metropolis from its glorious ruins. This, of course, has been a giddy, grand joint enterprise that thousands of us have been part of, and countless more have been affected by, even if they don’t know it.

Music: A matter of life and death

Back when we were leaving the 20th century, revolutionary pop music could open the space, energy and confidence to create your own destiny. Music was “a matter of life and death,” says Morley, not just today’s dreaded “content,” which he calls “mulch.”

“Now it’s just history,” he says unforgivingly. “The idea that popular culture had a potential importance in opening people’s minds and providing avenues of expression that would make the world a better place. If that’s over, then I felt it was important that I write it as a history of something that happened, another failed revolution.”

Self-correcting, he adds: “Or a suggestion that it can still be important because it increases sensitivity and connection with people, and it is about caring for life and for love.”

Streaming has drawn the radical sting from pop culture, he thinks, dissolving the time and the space needed for exciting new ideas to find meaning: “It’s difficult to get any genuine excitement from it because every day it is replaced with another face, another signal, another sound.”

Of the inferno of social media culture (he’s not on it), he says, “I guess I didn’t see the point becoming part of a torrent of communication that cancels itself out… I got the feeling it was unleashing monsters and shadows and demons.”

Here Morley is completely at odds with what Wilson would have done. Wilson gleefully embraced new platforms and channels, usually for them to be flamed and him to be shamed. Morley says: “Today someone that like that couldn’t operate, because he was sending out probes into the world – challenges and tests – perhaps the world now can’t understand ambiguity or nuance or suggestiveness or provocation. Everything is taken at face value.”

On pop culture’s playing field, Morley is the David Silva of writing. He finds spaces, creates angles, moves things along with little touches, then delivers a breath-taking cross-field pass linking the action.

He tracks the hidden ley lines that Wilson’s life reveals, from the Beatles to Buzzcocks, from Marple to Marx, from the Romans to The Ramones.

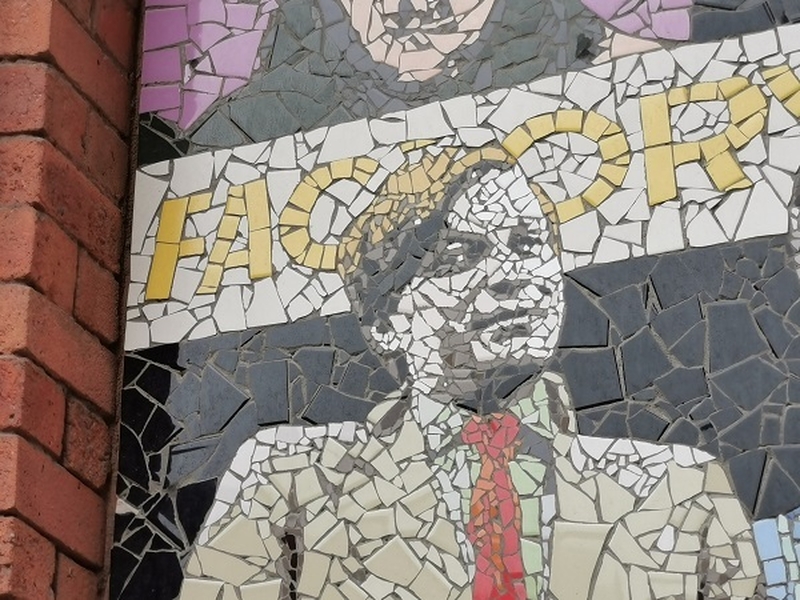

Factory and The Hacienda

As a pop culture lab experiment, he pinpoints Factory as the missing link between the Beatles’ failed Apple project and the data-tech vampire of today.

The book articulates the beliefs which shaped Wilson’s lifeforce, from Catholicism to Communism and situationism, how he changed his image (hat tip to stylist and store owner Richard Creme), and how we got from Factory punk gigs in a Hulme bus drivers’ club to the £180m-and-counting Factory complex in Castlefield thanks to the largesse of a Conservative chancellor, one George Osborne.

That’s some absurd crazy paving. If there’s no Factory/Hacienda, there’s no new shiny, skyrocketing Manchester (and Salford). Somehow, in its art, business and chaos mash-up, Wilson’s Factory - his “experiment in human nature” - cooked up the special sauce with which the city’s leaders built the new Manchester.

Football gave the city profile, but Factory gave it fascination and global sex appeal. Its output was pop culture as profound high art. Its music hit a nerve worldwide, its exquisite record sleeves hang in galleries, its cathedral of a performance space was somehow both a notorious crime scene and a palace of mass transcendence.

From Manchester with love

Morley’s book spins acute, multi-layered insights into music, culture and the very soul of the city. Rather than submerging yourself in the deep prose-poetry oceans of 2013’s The North, this book is more of a white water ride, pausing for captivating eddies and currents.

It drills into Wilson’s parents and early years, the unconventional family set-up, schooldays in Marple and Salford, his Cambridge University days (scraping a third due to student journalism and LSD) and his rule-breaking Granada TV broadcasts. He was so poor at school sports he was nicknamed "Plank". Wilson used words as a weapon to combat bullies, building up a force field of charm, arrogance and persuasion.

The original of the book’s cover photo, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, was taken in May 1985. I was standing behind Kevin Cummins when he took it for my (at that time) "alternative" magazine City Life. As Wilson peers out from behind a Hacienda pillar, he is captured smaller in the frame, less like the dominating TV big-head we saw in our living rooms.

His superpower was his cathode-ray charisma. The TV camera loved him. Being the next Michael Parkinson or David Dimbleby beckoned, but when he encountered Pistols’ manager Malcolm Maclaren, sparks flew, guiding Wilson down the path of cultural patron and provocateur.

The drugs, the gangs and the headlines

He revelled in the role of showrunner for the Manchester scene. But as Hulme-grey Manchester became dayglo Madchester, the whole circus big top collapsed under the drugs and the gangs and the headlines; the ringmaster exhausted, his clowns out of control.

In the 1990s, with Factory bankrupt, Hacienda demolished, personal finances dicey, marriage broken, there were still schemes and dreams – a beauty queen partner, digital downloading, urban planning and regional autonomy.

Morley’s book is no gooey celebration. The devastating first-hand emotional revelations of close family and friends are hard to read. Morley does not sit in judgement, his repeated "So It Goes" refrain both a nod to Wilson’s once-famous TV music show and a kind of cosmic shrug.

“To me, when you’re reading a book, you’re wearing a mask, and Tony would issue quotes, constructing a character that contained so many other characters, all this knowledge of other figures,” says Morley.

“I wanted to get that across, and once you feel you got Tony Wilson, he disappeared again and became someone else. These were all these favourite writers and he did know about them, it wasn’t superficial or show-off, he did really know and could use it in all sorts of ways. And they all turn up in the index in the afterlife, from Cilla Black to Dostoyevsky. All the people and information he had in his head, he seemed to be on the verge of a nervous breakdown, the amount of people he seemed to be able to collaborate or deal with, one of the key things he had was this unbelievable ability to assimilate all of us.”

In a 2003 note, Wilson wrote this to me: “There are things that you know and there are things that you feel, but they don’t become real until you put them into words, the right words.”

Paul Morley has taken 14 years to find the right words. Across 600 pages, each of the 51 chapters (51, get it?) weaves dream states with journalistic investigation, a tale of how one human being, with the help of like-minded spirits, psychically co-opted an entire city.

In the final chapter, Morley straps you into Wilson’s car for an exhilarating drive out of the city. The Mersey flows, the Pennines loom, you smell the aftershave and the drugs as the ideas flow and the multitude of Wilsons chatter away, and the galaxy opens up and the lights go green and Mr Manchester (and Salford) ascends to the stars.

I re-read that chapter last night and dreamed of Tony Wilson.

From Manchester with Love is published on 21 October 2021 by Faber (£20).

Paul Morley will be at HOME on Saturday 9 October at 3pm discussing his Tony Wilson biography with LoneLady (Julie Campbell).