My cardinal points

THE NORTH

Maybe we should all write down what our North is.

For me it’s a complex of positives and negatives which adds up to the only place I ever want to live. It fits me like a glove. Like an old sock. I know its ways, its bad habits and its peculiar joys.

Something that started a hundred years and more ago, the romantic ideal of continual process, a sense of communities developing is sliding away.

At its best it’s the spirit of independence melded with humour, at my end of the North that means Anthony Burgess, Robert Peel, John Bright, Lydia Becker, Elizabeth Gaskell, Elizabeth Raffald, Joseph Brotherton, Sam Bamford, Joan Bakewell, Anthony Wilson, hotpot, Lancashire cheese, steak and cow heel pie, curry, and pint after pint of golden ale.

It’s Morrissey and Doves and Hurts. It’s Caroline Aherne and Steve Coogan and Les Dawson. It’s Chetham's Library, United, Liverpool, City, Rochdale, LCCC and the National Cycling Centre. MIF. Multi-cultural. It’s the 25 Nobel prize winners from Manchester University. It’s liberating.

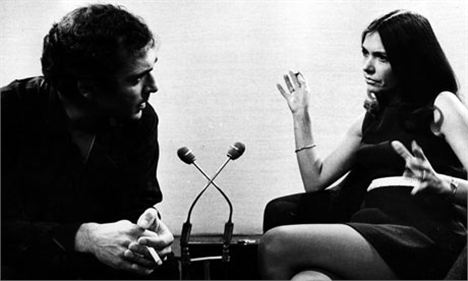

Joan Bakewell being interviewed in the 1960s as Paul Morley was growing up in Reddish

But it’s also Bernard Manning and 8% of a low-turnout voting Nick Griffin as Euro MP. It’s Shameless and people being somehow proud of that, it’s a chip on the shoulder, a vehicle for condescension, it’s understanding the anger that comes from that. It’s reductive.

It's the Miners Community Arts & Music Centre and Small Cinema in Moston, creating something out of nothing with their bare hands. It's innovation, entrepreneurship and radicalism.

The North is physical, visceral, a landscape beneath my feet.

It’s moorland and wooded cloughs, disused mills, grand Town Halls, church spires and council estates, weavers cottages and millstone grit, it’s brick, it’s brash, it’s high meadows and crazy sunsets at the end of dull days. (The main picture at the top of this page was taken on the hills above Shaw looking into Manchester at sunset.)

It can be breath-takingly more beautiful than anywhere else in these British islands and fifteen miles away it can be irredeemably uglier than anywhere in these British islands.

It’s a mass extinction, revealed in massive masonry by the side of rivers, peeping from under greenery. A place where you guess a factory once reared high above, where hundreds of humans worked long hours in clog and shawl at a time when through the Royal Exchange in Manchester 6.6bn linear yards of cloth flowed with nearest rival Japan producing but a paltry 56m linear yards.

It’s the spark that’s left the furnace.

It’s a sense that maybe the really important times are over. That every dog has its day and that we’ve had ours. It’s the hope that if we once had all that, then the North can rise again - and is rising with the move of the Beeb and the transformation of Liverpool and Manchester. It’s the doubt that much of this new money wasn’t generated anywhere here in the North.

Post-industrial city, sunrise or sunset?

It’s the almost hand-moulded hills of the Trough of Bowland, the sandstone and views of Alderley Edge, the sheer effortless beauty of the Lune Valley, the can-this-be-real drama and gentleness of the Lake District, the ludicrous sand dunes at Formby.

It’s the empty urban areas of east and north Manchester, the shattered districts of inner Liverpool, demoralised small towns like Radcliffe and Widnes. It’s boarded up pubs and shops and worse, the hundreds of cut off, isolated, estates such as Langley or Hattersley or Kirkby that make me seethe with rage about the inhuman planning disaster of post World War II Britain – that internal diaspora played out with more brutal potency in the heavily populated North than just about anywhere.

It’s the endless transition between well-to-do and poor, between haves and have nots, between wilderness and towns.

It’s the place where you see the skull beneath the British skin more obviously than anywhere else. The North is the rough with the smooth. It’s where, as Jim McClellan wrote, ‘the social processes are more visible’.

Yet the North is all about the people who’ve achieved, not through privilege and inheritance, but through ‘nous’ - although I know I may be kidding myself.

And losing steam.

And repeating myself.

Because of course when I talk about the North I’m only really ever talking about the North West, my bit.

And I’m only ever really talking about me.

Paul Morley’s cardinal points

This is what Paul Morley has done in his 580-odd page book The North, talked about himself and his North.

And he invites us all to do the same.

“It’d be lovely if people did something similar themselves, made a record, a list. Maybe this is a template for that. It’s a book for the Google age I think. Or what a book can be today in response to the digital world. It’s a way we can adapt and find our own North. That’s an audacious idea, but it’s my belief,” he says.

Paul Morley

The result of Morley’s vision for the book, for us and the future of literature delivers a peculiar result.

It’s part narrative of Morley growing up in Reddish, that half-land between Manchester and Stockport, it’s part history text of his part of The North or rather the bits he feels most comfortable with such as Manchester, Stockport and Liverpool.

It’s also a very engaging Wikipedia of characters and incidents delivered in a different typeface to the main narrative with a simple date for a title and then a paragraph or two of content.

“The structure is unusual perhaps, but it seemed the right one,” he says. “I wanted the form to represent the sense of the book, moving through shapes and making journeys and allowing these great northern characters to babble and tell a good story in a way that seemed part of where they came from.

“Interspersed is my memoir going forwards and backwards. History swirling forwards and backwards with it. The people swirling around too. The North isn’t one narrative, it’s thousands, millions, and I wanted to catch this metaphorically.”

The North, switching this way and that

It’s an interesting device, but it doesn’t always work. The ‘northern characters’ and the little factoids (I love that Hugh Charles from Reddish wrote the Vera Lynn classic ‘We’ll meet again’) become the bits the reader chases down, sometimes glossing over the more complex Morley memoir written with his usual multi-layered punch.

Now more than ever

Morley thinks this is a good time to write about the North.

“The present younger generations are moving into the screen and this will only accelerate. They don’t see the North the same way as I did growing up. They have a global reach now digitally and aren’t as tied to time and place. I didn’t have that growing up.

“When you look at the music scenes in British cities back in the seventies and eighties, they were local, rooted in the historical and physical nature of the locations from where they came. Merseyside felt different from what was taking place in Manchester which in turn had a scene that felt very different from what was happening in Sheffield. “

"People were proud of those differences but today everything is more linked, international, through technology. Kids can pick and choose from anything across the world that appeals and interact with it. Listen I’m not saying this is a bad thing, but it’s different from what I knew and leads to different results.”

So is The North as an idea dying? Can identity survive the digital age?

“Certain elements will linger but even accents are getting more generic, the difference between a Stockport and Rochdale accent isn’t so clear in 2013. Something that started a hundred years and more ago, the romantic ideal of continual process, a sense of communities developing is sliding away. Instead of districts and areas having similar outlooks, the individual takes over, the international individual, and paradoxically the more individuality there is the more uniformity we have. More access to more things has meant more and more of the same.”

But was there ever a North in the sense of Morley’s book? Does he even have it himself? His work here is very North Western, there’s not much on Hull or Newcastle; Sunderland and Middlesbrough don’t even get a mention.

Not much Newcastle

“The book is The North as I perceive it. My North. I think across this whole area there is a shared outlook. There’s intense rivalry, but the truth is that while we compete, the other areas are on my side. The content of the book does cover, especially through the Northern characters in there, in the anecdotal sections, every part of The North and all the people who have possessed it.”

Voice of unreason

Maybe, but a north easterner will still probably feel short-changed by the book.

What all in The North might agree on though is accent.

When I went to university back in the eighties a Twickenham lad, who has since become a good friend, confessed after a few months that, when he’d first heard my Rochdale accent, he’d just assumed I was thick.

“In my work, throughout my career, I have tended to be used as cultural rough, a joke. And that’s all down to my accent,” says Morley with a laugh. “There’s a contradiction in this. You could say the southern accent, especially received pronunciation, is fey and superficial yet the accents that seem more British, stronger and more authentic, are patronised. This still goes on - of course in terms of influence and power the former wins.”

Morley mentions Liam Broady, the young Stockport tennis star, who has had problems with the All England Club. Morley writes in the book how even in the 21st Century ‘a so-called provincial accent represented a blunt, uncouth attitude that was somehow fundamentally unschooled and trouble-making’. The All England Club might disagree of course, their side of the argument is missing.

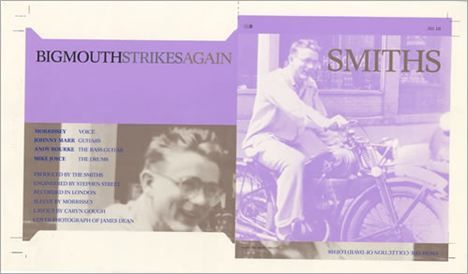

The Smiths - big northern mouth strikes again

Do we in the North make too much of accent-prejudice. Maybe. Maybe not. I know of a BBC producer ahead of the move to Salford who had a tour of the city and declared he loved it: "But I won't be moving up, I wouldn't want my children to talk like you," he said, without tongue in cheek.

There are some sub-editing problems with the book. There are several errors of fact, one or two hilarious, calling the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857 the Great Exhibition is missing a big historical point, while referring to the Refuge Assurance building on Oxford Road as the Refugee Assurance building brings a smile – how very progressive.

As befits a man from Stockport, the word ‘viaduct’ appears more than in any other work known to Man including The Observer Book of Viaducts.

A fading Northern worldview

Morley doesn’t think The North a ‘sentimental book’ but there is a sentimental element to it. This is unavoidable. He is looking back at a place he left. That necessarily delivers an air of nostalgia.

It’s about him moving away, yet not losing his ‘Northernness’ because it made him, provided him with his world view, his weltanshauung.

“I’ve never turned my back on The North, it was always simmering away there.”

In the book Morley quotes fellow sentimentalist Morrissey in an interview: “You’re southern – you wouldn’t understand. When you’re northern, you’re northern forever and you’re instilled with a certain feel for life that you can’t get rid of. You just can’t.”

Many of us, like Morley, like Morrissey, feel the same. But that intensity of identity that either induced pride or flight seems to be fading.

Not because people, kids, don’t think they’re from the North anymore and aren’t proud (or ashamed) of that, rather in the global digitalised age we are losing the signifiers, the dialect words, the way of dressing, the way of working, the trad foods, the stories, the muck maybe, the brass too, even the buildings that were the hard millstone grit of our lives.

As Morley says, that’s not sad, in fact it’s liberating, but it is happening. The North will not be the same, will not mean the same.

Time, maybe to make that list.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter here @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+

The North (And Almost Everything In It) is out now. Price £20 from Bloomsbury.

Paul Morley will be talking to Dave Haslam at Gorilla on Whitworth Street West on 14 June, you can book here.