As leaseholders are asked to stump up costs, is it time we turned the sprinklers on the property barons? By Danny Moran.

The news that residents at two Green Quarter tower blocks are being asked to pay for their buildings’ cladding to be replaced is merely the latest spectacle to be seen at the ideal homes atrocity exhibition currently touring the nation.

Post-Grenfell, it implies a conspiracy against the home owner which goes beyond the realms of satire.

Among the manicured lawns and frothy little fountains at the Redbank district, just a stone’s throw from Victoria Station, are Vallea Court and Cypress Place: at fourteen and eighteen storeys respectively, just two of the 323 residential blocks which have been identified, nationwide, as having the lethal ACM composite in their exterior surfaces.

Ignominiously, Manchester and Salford are two of the six local authorities which have been revealed to have eleven or more non-compliant blocks under their jurisdiction.

The aluminium composite is thought to have been a major contributor in the deaths of 72 people when fire swept through a North Kensington high rise last summer. Yet who, down at the Green Quarter, is deemed responsible for replacing it?

Incredibly, that would be the residents, so it would seem.

The government allowed it, the industry knew about it, the architect chose it, the developer installed it, the council approved it, the realtor washed their hands of it, the experts dubbed it “more flammable than petrol” … yet somehow it’s the leaseholder who is liable to pay to have it fixed.

Welcome to the deregulated reality of post-crash, pre-Brexit Britain.

What sticks in the craw is that they want to bill us their legal fees for the expense of bringing the case against us

Going green

Irene Wilcox and her husband bought their two-bedroom apartment back in 2012, when the prevailing wisdom was that property was worth more than money in the bank. In an up-and-coming area close to both the train station and NQ4, the Green Quarter seemed the perfect location for a buy-to-let investment.

“The interest rate after the crash plummeted,” she recalls. “The government and everybody else were saying ‘buy property’. So we took our pension money out and thought ‘well okay, we’ll put it in an apartment’. The plan was to rent it out for ten years and then sell it.”

That plan hit the spikes after last year’s safety checks were conducted and freeholder Pemberstone got in touch to say they would be asking them to put their hands in their pockets to fix a badly-built skyscraper.

Which is where the small print on the lease comes into its own, of course.

“It was just a note through the tenant’s door…” says Irene. “It upset me because my daughter was diagnosed with cancer in November and I’ve other things on my mind. So this has come as an unbelievable shock. Of course, I wrote and asked them about it. And that’s when the paperwork started to arrive…”

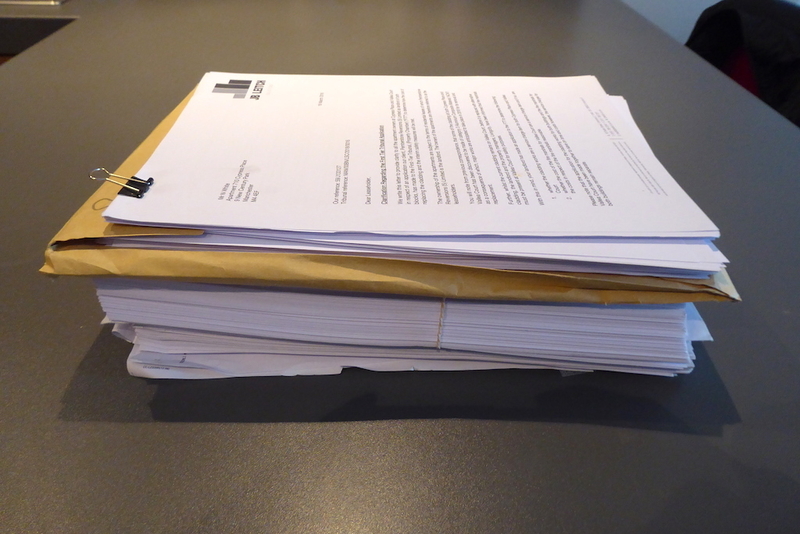

Neighbour Nick White shows us the mansion of documentation he too has received since Pemberstone got wise to the fire safety farrago. Hundreds of pages at a time in successive batches: a textual netherworld, seemingly, where legalese, jargon and waffle conspire to haunt the reader with intimations of culpability.

The 35-year-old HR manager purchased his seventh-floor pad in 2014. Back then, he remembers, the Sunday Times were hailing the development as one of the best places to buy in the land. Four years on, having climbed Mount Papermanjaro, he last week found himself dragged along with other residents to a hastily-convened tribunal, in a bid to determine definitively who will foot the bill.

“Not that there’s really any doubt about that from a legal standpoint,” he points out. “Unless the government were to step in and legislate.” Like his fellow leaseholders, Nick believes the purpose of the pre-emptive hearing was to railroad residents into accepting the inevitable. “They just want to clarify who is liable so they can rubber stamp whatever follows. And we’ll have to accept it.”

Pemberstone have cited £10 000 per resident as a likely estimate. But as nothing has been properly costed yet it’s widely believed that that figure has the potential to rise dramatically.

“What sticks in the craw is that they want to bill us their legal fees for the expense of bringing the case against us. That will go on our management fee too, if they’re successful.”

So that’s quite a lease you’ve got there, the reader may note. You’re lucky you’re not being asked to shell out for a brand new building.

This shows that leaseholders don’t really own their own homes... it’s in some ways a more expensive form of renting.

A landlord down under

Accounts of the hearing lay bare the sense of buck-passing attending the dispute. How can this be the residents’ fault? Why do the management company, Living City, seem to think this is a fait accompli? Why don’t Pemberstone go after the original developer, Lendlease? And how can the city council, for that matter, be courting Lendlease to manage the town hall?

The Australian property giant, headquartered in Barangaroo, Sydney, last year recorded pre-tax profits of $1.2bn.

As the company who built the two tower blocks, would it not make more sense for Pemberstone to seek compensation from them? Pemberstone told us they are “in dialogue” with the landlords down under, which is nice. Perhaps they could counsel each other on the unfolding public relations apocalypse taking place beneath their feet.

For housing campaigner Ruth London there is a deregulation parable to be drawn from a situation in which residents are asked to somehow find ten grand down the back of the sofa.

Sofas were made safe back in the 1980s, you will recall.

“It’s completely unacceptable that so many people are still in danger of fire,” she tells Confidential. “It’s a year on from Grenfell now, and progress is at a snail’s pace. This shows that leaseholders don’t really own their own homes. They’re subject to all sorts of conditions. Standing charges going up without notice, and so on. It’s in some ways a more expensive form of renting.

Residents are being forced to pay for something which is not of their making, and it can ruin people. There are people who’ve ended up in hospital because of the stress. Set this against the fact that there are people who have made a lot of money out of property, on the backs of people they’ve skimped on basic materials.”

The outcome of the tribunal won’t be known for several weeks. Meanwhile neither the council nor the government will release a list of premises which have been found to be non-compliant.

No word from Whitehall, then, on rumours that the Chips Building could fry at any moment.

Asked why the secrecy, the council referred us to the housing ministry, who told us they weren’t prepared to offer a reason. But with a bit of prodding, the combined authority disclosed to us that there are a whopping 73 high rises in the Greater Manchester area which have been found to be in breach of the checks, the vast majority of them having the Grenfell-type ACM cladding.

Of these, 42 are social housing whose residents will not be asked to pay. With one or two possible exceptions, it’s expected that the majority of the remaining 32 privately-owned blocks will be seeking to secure the cost of re-medial work from leaseholders.

In the meantime, residents at the two Green Quarter towers, and many others besides, are acclimatising themselves both to the financial consequences and the new realities of living in a dangerous tall building. Along with its flammable cladding, Cypress Place has just a single staircase down which hundreds of people would be expected to evacuate in the event of a blaze.

Fourteen-storey Vallea Court, on the other hand, boasts the full house of: tinderbox cladding, single staircase, no general smoke alarm, and no sprinklers. In place of these a walking warden now tramps the corridors, 24/7, his hourly wage having been added on to the residents’ generous tab.

We could still be here in 2025. You find yourself wondering: how do I get out here? Do I need to buy a rope?

Let them eat fire extinguishers

“Watching the documentaries about Grenfell and seeing how quickly the fire spread makes me very nervous,” says Nick, when asked about the mood in his block. “All it takes is one idiot who can’t afford to pay to lose his mind and start a fire. With so many tower blocks and a finite number of contractors you worry that this could all take a lot longer than has been advertised. We could still be here in 2025. You find yourself wondering: how do I get out here? Do I need to buy a rope?”

As a non-residential owner Irene is hardly less perturbed. She worries about losing her pension. The properties are worthless, currently, as no one will lend against the risk. Thoughts of bailiffs, county court judgements, repossession are never far away, and the emotion in her voice is well-worn.

“We’ve been stitched up,” she splutters. “If we’re hit with a ten thousand pound bill we’re going to be in dire straits. You start thinking about what you’re going to have to sell. I can’t sell my car because I need it. So what do I sell? You start thinking: when it comes down to it, in the end, will I have to sell my own home?”

Solutions to these problems aren’t difficult to devise. As Ruth says: “The replacement of all cladding and the provision of sprinklers should be funded by the government. And in the longer term, we need regulations to protect people. Those who are responsible for this kind of thing have to be held to account, and residents’ voices need to be listened to. That was what was so evidently absent at Grenfell, and it has to change.”

Deregulation may be seen to have done little for our trains, our wages and our utility bills, and so it is with housing. The consequences of Mrs Thatcher’s ‘bonfire of red tape’ for fire safety have been well rehearsed over the last twelve months, but there is a story here too about the leasehold system which cuts to the heart of the property debacle. Just as Captain Cae0s found last year, just as the residents at Royal Mill and other places caught in ground rent traps have found, just as the good people of Cypress Place and Vallea Court are finding in the wake of the cladding fiasco, your lease can be little more than a surrender to powerful interests.

Until regulation is introduced and leasehold reform taken seriously, the whole market remains on the brink of all manner of woes.