GASKELL HOUSE is a sweet new Manchester attraction and unusual too.

I bethought me how deep might be the romance in the lives of those who elbowed me daily in the busy streets.

As a city we lack historic houses, both grand and humble, open to the public and those we possess have usually been treated outrageously by Manchester City Council, often because of a lack of money, but equally through downright negligence.

Presently, Heaton Hall and Wythenshawe Hall are mothballed and the former, a building of national significance, needs urgent restoration work on the west wing. Clayton Hall opens once a month, Baguley Hall even less frequently.

It's not just the council though. Historic houses in private ownership can be an utter disgrace, such as Hough Hall in Moston, while Slade Hall in Longsight is fading fast.

The remarkable Hough End Hall in Chorlton, disgarded and sold-off by the council, has at least become the focus of attention through an energetic Friends group - indeed we have to thank Friends groups generally for the care they offer many of these buildings.

That just leaves Ordsall Hall in Salford and Platt Hall in Rusholme to reflect Manchester's domestic building legacy.

Or it did until recently.

The Gaskell House on Plymouth Grove has reopened after a £2.5m restoration and is an absolute delight. The joy lies not just in the scale of the place - this is a livable home, not a 'stately home' - but in its associations.

Not only did one of the country's great nineteenth century novelists, Elizabeth Gaskell, live here for many years but the house hosted a roll call of nineteenth century luminaries including Charles Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Ruskin, Charles Halle and Elizabeth's good friend, Charlotte Brontë. Elizabeth Gaskell wrote the biography of the unpredictable Yorkshire woman in the house after the latter's death in 1855.

Elizabeth Gaskell

Why was the house such a magnet?

This was down to the Gaskell's themselves, who lived here from 1850 until 1913.

These gentle reformists were Unitarians, a thoroughly free-thinking religious sect. They believed in equal education for men and women, equality of opportunity for all classes of people, tolerance of others and they utterly rejected the 'seen but not heard' attitude to children; essentially all the rights and values progressive 21st century folk embrace.

The most famous of the Gaskells, was the aforementioned Elizabeth, writer, novelist, mother, gossip, traveller and general good egg.

She was already a published writer before her novels, but the death of an infant son, threw her into despair. It's said, to take her mind off the pain her husband, William, encouraged her to write her first novel, Mary Barton. William, by the way, was the minister at Cross Street Unitarian Chapel and a man heavily involved in social and educational initiatives, he dismissed the idea of original sin and believed humans were innately good.

Elizabeth was clear about her objectives in novels from the start.

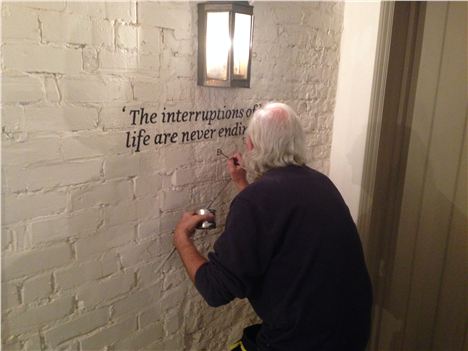

In the preface to the Mary Barton she says: ‘I bethought me how deep might be the romance in the lives of those who elbowed me daily in the busy streets. I had always felt a deep sympathy for the careworn men who looked as if doomed to struggle through their lives in strange alternations between work and want.’ Her purpose was to show the ‘other Manchester’, the other Britain, ignored in the salons of polite society.

For a middle class woman of the mid-nineteenth century to touch on subjects such as crime, poverty and prostitution was courageous, even provocative. In her novels, too, there’s often a returning son, a poignant nod to her dead infant lad, who's death lay behind that first novel.

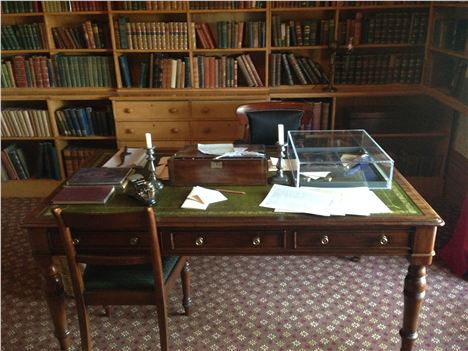

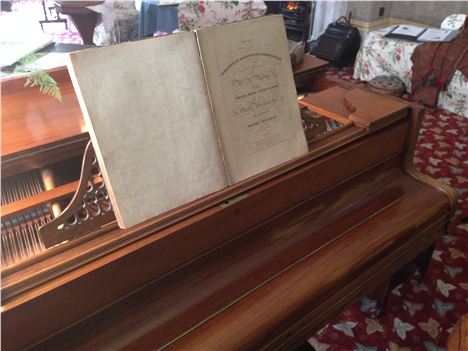

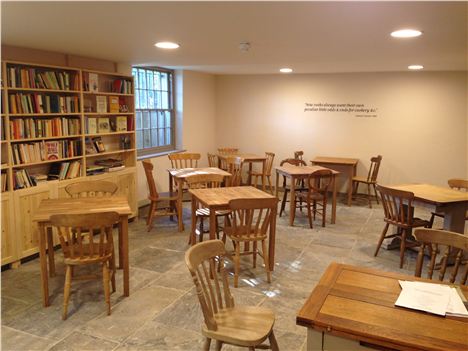

In the reopened neo-Greek house on Plymouth Grove - restored to how it might have looked in the 1850s - you can see William’s study, the dining room where Elizabeth wrote, the lovely drawing room where Charles Halle taught piano to Marianne Gaskell and the morning room. There’s a café downstairs too. As funds come available other rooms including a bedroom will be restored.

The architect it seems was probably Richard Lane (Friends Meeting House, 84 King Street - now a Pizza Express) and the building would have been finished by 1838.

Detail from the Neo-Greek decoration

Two unmarried Gaskell daughters lived on in the house until 1913 when the last one, Meta, died.

The Spectator wrote a moving obituary about the role the family and Meta had played in Manchester.

‘Everyone who was distinguished in letters, music, painting or scholarship gravitated to the house in Plymouth Grove. Probably no such gatherings of accomplished people have ever been organised in an industrial town. Miss Meta Gaskell laboured for Manchester to the day of her death. She was a great citizen, a great friend, a great optimist. Manchester will not soon be able to measure its loss; but let us hope that the example may mean much, not only there, but in other great towns where the secret is known that the life of England has not its chief, much less its only, source in London.’

It’s excellent news - through lottery grants, the indefatigable energy of Janet Allan, the long hours of the volunteers, the work of John Williams - that Manchester has that rarest of visitor attractions in this city, a fine historic house: even better it has one which has played an honourable role in the cultural history of these islands.

The Gaskell House is at 84 Plymouth Grove, M13 9LW, and is open Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays – 11am-5pm.

Adults: £4.95, Concessions (Senior citizen and students): £3.95, Children under 16: free (must be accompanied by an adult). The money goes to further restoration and maintenance, all the staff are volunteers.

You can hire the building for dinner, capacity twenty for a sit-down meal, or you can get married there or civil partnered-up - of course.

You can follow Jonathan Schofield on Twitter @JonathSchofield or connect via Google+

If it's under perspex is a Gaskell artefact

If it's under perspex is a Gaskell artefact

The oculus above the stairwell to let light in

The oculus above the stairwell to let light in

Rear view, Elizabeth wrote in the bay of the dining room