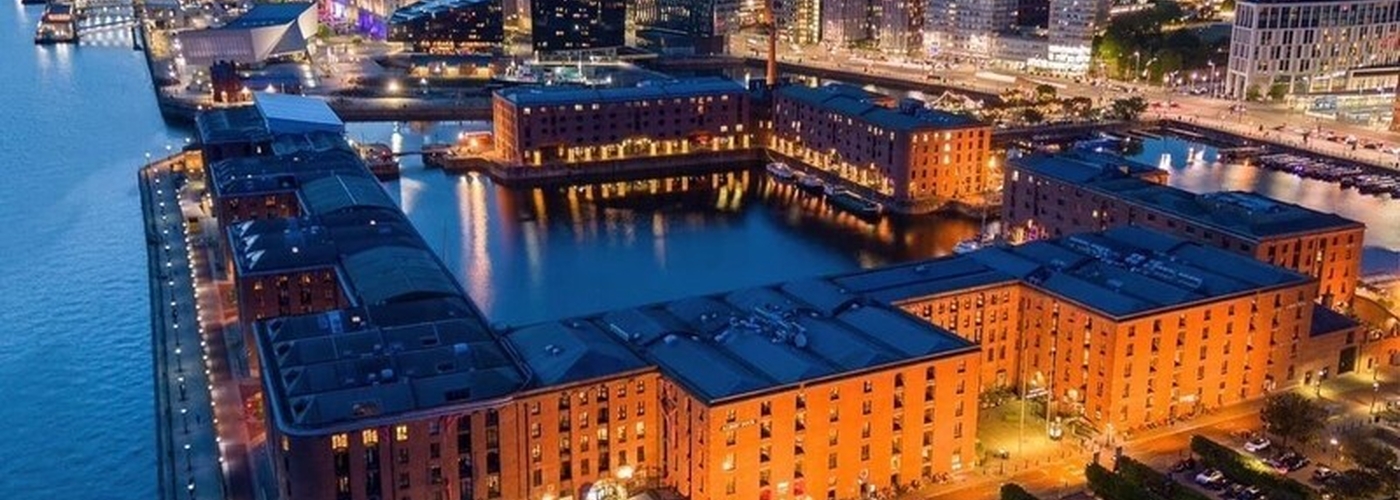

Tate Liverpool closes for a refurb and Britannia Pavilion to be refreshed

Big changes are to take place at Albert Dock. The most significant will be Tate Liverpool’s major £29.7m refurbishment, including a £10m grant from the government's Levelling Up Fund.

Meanwhile on the south side of this mighty set of Grade I listed structures General Projects and Neo Capital have submitted plans to refurbish 20,000 sq ft of existing workspace in the 375,000 sq ft of Britannia Pavilion which hosts The Beatles Story.

Part of the plans include new double-height galleries to accommodate larger contemporary works

The acclaimed complex of dock buildings designed by Jesse Hartley and opened in 1846 are some of the best known and familiar structures in the UK, and have been described as ‘the finest examples of their kind in Europe’. This means any interventions have to be incredibly sensitive.

The Tate will close from 16 October and reopen in 2025. During the closure, Tate Liverpool will work at other projects across the city and region.

The architects for the project are London’s 6a Architects. Part of the plans include new double-height galleries to accommodate larger contemporary works which were previously impossible to display at Tate Liverpool. Elements of the award-winning Stirling and Wilford design from 1988 will be retained.

Helen Legg, Director of Tate Liverpool, has said: “We are proud to be the UK’s most visited modern art gallery outside London but, after 35 years, we want to do more to engage new audiences and to reduce the gallery’s impact on the environment. Through this once-in-a-generation renewal of Tate Liverpool we will become an art museum fit for the 21st century, serving the needs of artists and audiences, now and into the future while continuing to play our part in the ongoing evolution of the historic waterfront.”

Across the dock, Britannia Pavilion, which was bought in May for £40m by developer General Projects and investor Neo Capital, is to be partly spruced up from designs by Studio Mutt.

Jacob Loftus, chief executive of General Projects, in an interview with Place North West said: “The plans have been put forward to transform 20,000-sq-ft of vacant mezzanine space into fully-fitted SME workspace units which will support a cluster of independent, creative businesses onto the campus.”

Loftus made assurances about the quality of the refurbishment and how it will be very much in keeping with the Albert Dock complex.

Studio MUTT, an architectural practice from Oriel Chambers on Water Street, said: “The simple but monumental use of brick paired with iron to create large vaulted open spaces creates a powerful and unique atmosphere.” They want to “rationalise the layers of intervention that had been undertaken over the last 40 years by mostly opening up as much as possible to reveal the original skeleton brick and iron of the warehouse and make this the main feature.”

A bit of history

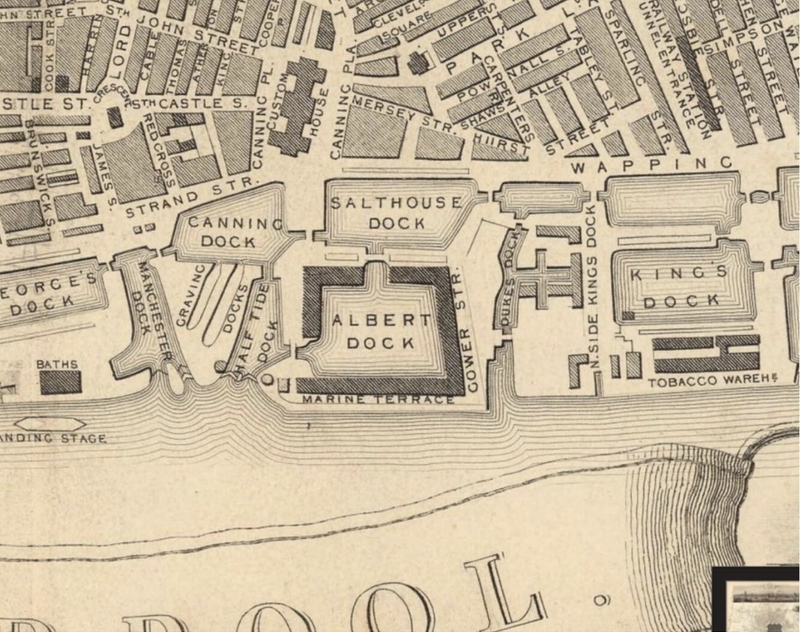

Between 1824 and 1860, Jesse Hartley, the docks engineer, more than doubled the dock accommodation in the city. Clarence Dock and Clarence Graving Dock opened in 1830, with Waterloo Dock completed in 1834. By 1836, Victoria and Trafalgar Docks were open, and along with Waterloo Dock they formed a uniform trio of inter-connecting water spaces, with river access gained through the Victoria Dock lock gate.

However, his most celebrated dock, and the warehouses which surround it, was the enclosed Royal Albert Dock, which followed the Dock Act of 1844. Designed by Hartley, along with Phillip Hardwick, who had earlier worked on London’s Docks, Royal Albert Dock was opened in 1846, and was constructed entirely of cast iron, brick and stone/granite, with no structural wood. In 1848 it was equipped with the first hydraulic cranes in the world, and cargo handling was based on the loading and unloading directly from the ship to warehouse. It served as the main dock for cotton, tea, silk, tobacco, ivory and sugar, and in association with Salthouse Dock.

The Royal Albert Dock complex has been described by architectural guru Nikolaus Pevsner in 1969 as ‘one of the finest examples anywhere in Europe of romantic architecture parlante, i.e of expressing the strength of resistance to water and the bulk of ships’.

James Stevens Curl, the architectural historian, has written that ‘some canal and dockside architecture seemed to point towards a new style where Classical relationships of proportion, solid and void, and integrity of geometry would be paramount, but stripped of all the tyranny of overt use of the Orders, and minus all decorative frippery.'

The Royal Albert Dock was one of those rare cases, Curl believes, in which this style was achieved: “These are the most Sublime of all nineteenth-century examples of commercial and industrial architecture, with their cast-iron unfluted Doric columns, massive undecorated brick walls, repetitive elements, and avoidance of ornament.’

The docks declined after World War 2 and closed in 1972. There were several ideas including a berserk one from Liverpool City Council to use the basin as landfill. Fortunately the value to the city and to the nation of Albert Docks was eventually realised and the complex was repaired, restored and fully re-opened by 1988.

Main image above is from Andy Mallins and his incredible drone pictures.

If you liked this you might like:

Liverpool waterfront set for a single major masterplan

Drama of the city from above

North city developments: are they tall enough

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!