Joanna Williams tells the forgotten story of a suffragist, scientist and trailblazer

Why would anyone want to write a book about Lydia Becker, a woman who died over 130 years ago, of whom no-one has ever heard? Actually, it's not strictly true to say no-one, as now there is a Lydia Becker Institute of Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases in the University of Manchester, a Lydia Becker Way in Chadderton, and Lydia's tearoom at Foxdenton Hall. So Mancunians are gradually waking up to the fact that, as well as the dazzling Emmeline Pankhurst, Manchester produced another great campaigner for women's rights a whole generation earlier.

The ground was prepared and the seed was sown; the rest is history

Born in Manchester, but growing up in middle class comfort mainly in rural Altham near Burnley, Lydia was the eldest of fifteen children. She had no formal schooling but read voraciously and her letters show that she resented her lack of education and opportunity for a career. She determined to use her rural setting and became a serious botanist, making accurate records of plants, and writing a simplified scientific guide, Botany for Novices.

After she moved with her family in 1865 to Manchester, city of social and political ferment, she attended a speech by London campaigner, Barbara Bodichon. She was thrilled to discover that there were others who felt as she did that women were getting a raw deal. Lydia regarded the vote as crucial; its achievement would mean recognition as citizens and power to effect change for women. For over twenty years as the secretary of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage she charmed, argued and bullied to drive the campaign forward across Britain. For the final nine of those years, she also led the London society as their parliamentary agent, steamrollering in to lobby MPs and ministers as no woman had ever done before.

Using a loophole in the law, Lydia persuaded women with property to register for the 1868 general election, and indeed up to thousand of them across the country cast their vote. It seems likely that this approach was suggested to her by the experience of Lilly Maxwell, a Manchester widow with her own crockery shop.

In a by-election in the city in November 1867 Maxwell's name somehow got onto the voters register; how this happened is mysterious. The Times thought that the Manchester suffragists had managed to sneakily register the unsuspecting lady. They strongly denied the accusation, but Becker quickly took Lilly under her wing, made sure that she got to the poll in Chorlton-on-Medlock town hall, and was able to cast her vote for Jacob Bright in front of a, no doubt, bemused room of officials and male voters, who promptly gave her three cheers.

The actions of Lilly Maxwell and of the many women who voted in the general election of 1867 disproved arguments that women did not want to vote or have the mental capacity to do so. But in a high court judgement the traditional view that women were too frail and lacked the intellectual capacity to vote prevailed and the loophole was closed. That didn't stop Lydia and her colleague, Alice Scatcherd, from visiting the Isle of Man in 1880 and persuading the Tynwald to give women the vote on the same terms as men. It took another 48 years before the rest of the UK followed suit.

The issue was kept on the boil in parliament with the presentation of a bill or a resolution for women's votes almost every year from 1870. At the start the campaigners encountered entrenched prejudice; in 1873, one MP remarked he 'did not like to see women enter into competition with dancing dogs, to show their wonderful powers in doing things which it is not expected they will do'. But gradually MPs began to take the question seriously. By 1890, they were properly debating women's votes and many were in favour. And this was thirteen years before the Suffragettes began their agitation.

The accusation that before the Suffragettes the women's campaign was only interested in the middle classes is patently untrue in the case of Lydia Becker. When a bill modified the electoral system for municipal corporations like Manchester, Lydia successfully suggested an amendment to give a vote to women householders, many of whom were working-class. She then held a series of women's meetings to explain the process and encourage them to question candidates about their policies, and even to stand themselves for the local school board or poor law board.

As the only woman on the Manchester School Board herself for 20 years, from its beginning until her death, she worked assiduously for the education of poor children. It was an effective way of showing that women were capable of success outside the domestic sphere. It also allowed Lydia to push for equality for girls in education. She demanded equal capitation with boys and access to academic subjects for girls. And she pithily announced that 'if she had her way, every boy in Manchester should learn to darn his own socks and cook his own chops'.

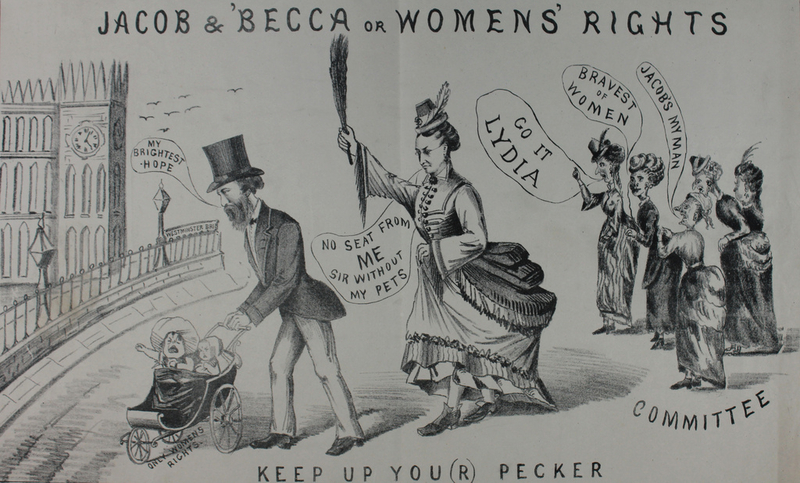

The path of a mover and shaker has never been smooth. Lydia was attacked in the press and parliament with jibes which were intended to humiliate. Hostile cartoons showed her and her colleagues as aggressive, strident, ugly, scruffy and manly.

For women brought up to be retiring, passive and silent in male company, the public indignity of these attacks was hurtful, even alarming. But an increasing number of people were won over, in parliament, in political parties, and amongst the general public.

In 1874, a fourteen year old Emmeline Goulden (later Pankhurst) was taken by her mother to a women's suffrage meeting in Manchester. She recalled in her 1914 autobiography that she heard 'the great Miss Lydia Becker' speak and as a result she came out 'a conscious and confirmed suffragist'. The ground was prepared and the seed was sown; the rest is history.

Joanna Williams is the author of several books including biographies of Manchester greats such as Abel Heywood and Lydia Becker.

To purchase a copy of The Great Miss Lydia Becker visit the Pen and Sword Books website

Read next - Piccadilly Gardens: plans, projects and dreams that never happened

Read again - ‘City Visitor Charge’ - will the Manchester ‘tourist tax’ benefit all?

Get the latest news to your inbox

Get the latest food & drink news and exclusive offers by email by signing up to our mailing list. This is one of the ways that Confidentials remains free to our readers and by signing up you help support our high quality, impartial and knowledgable writers. Thank you!