AS THE nineteenth century became the twentieth century Edgar Wood (1860–1935), one of the most elusive and brilliant architects this country has ever spawned, designed the First Church of Christ, Scientist in Victoria Park. The building was complete by 1904 and is a ten minute walk from the Whitworth Art Gallery and five minutes from Victoria Baths.

A great creative power in which a certain poetic gift is dominant

It was described by Britain’s most famous architectural commentator, Nikolaus Pevsner, in the Buildings of England series as ‘a pioneer work, internationally speaking, of an Expressionism halfway between Gaudí and Germany about 1920, and it stands entirely on its own in England.’

The bringing together of Arts and Crafts with Art Nouveau and marrying them to a desire to be ‘modern’ yet beautiful was one of Wood’s hallmarks. You can see these qualities in all his twenty-plus listed designs including Long Street Church and School in Middleton (1901), his Elm Street School (1908) also in Middleton and the house he built for himself in Hale, Royd House (1914).

First Church of Christ Scientist - 1904

First Church of Christ Scientist - 1904

Detail on the door plate, also designed by Wood

The attention to detail and the flair of the designs seems to fit the character of the man exactly. As the chief scholar for Wood, John Archer, has written: ‘(Wood’s) individuality was conspicuously displayed by an eccentric and flamboyant taste in dress. He wore a voluminous black cloak lined with red silk, a broad brimmed hat and carried a silver-handled cane; and he had a dachshund which he called ‘Lily Lies Low’. (Yet), he was no effete dandy but a man of great vehemence, determination and prodigious energy.’

Edgar Wood: aesthete

Edgar Wood: aestheteDespite his relative lack of fame in Britain outside architectural circles, he was well-known across the art world during his working life. As David Morris in his fine essay on Edgar Wood says: ‘Wood’s work was exhibited at the Architectural League of New York in 1900 and at the international exhibitions of Turin and Budapest in 1902. He was published in foreign architectural journals as well as in British publications.’

Deutscher Werkbund member Hermann Muthesius in his internationally renowned work Das Englische Haus (1904) placed Wood alongside Rennie Mackintosh, Voysey and Baillie Scott characterising his buildings as ‘exceptionally interesting’ and describing him enthusiastically, as Morris reveals, as ‘one of the best representatives of those who go their own way and refuse to reproduce earlier styles’. Wood is described as having ‘a great creative power in which a certain poetic gift is dominant.’’

Royd House. Wood built this for himself. The car isn't his. Probably.

Royd House. Wood built this for himself. The car isn't his. Probably.Wood was born and brought up in Middleton, four or so miles north of Manchester city centre, the son of a cotton manufacturer. He was supposed to join the family business but instead he favoured becoming a fine artist. The compromise agreed with the family was that he apply himself to the more practical art of architecture – although he would design tilework, furniture, friezes and so on all his life, becoming a founding member of the Northern Art Workers’ Guild in 1896.

Many of his commissions came through extended family connections and most writers agree that he preferred smaller commissions over which he could exercise full control. Thus his work is frequently domestic with a few churches, small commercial buildings and street and park furniture ranging from water fountains to the 83ft Lindley Clock Tower in Huddersfield.

He may even have been behind this lovely typeface (below) on the Manchester School of Art Extension now part of Manchester Metropolitan University. Certainly this was the work of the Northern Art Workers' Guild probably working with the celebrated WJ Neatby just a year after the Guild was formed. The typeface looks very close to Wood's typefaces of the time.

Did Wood work on this too?

Did Wood work on this too?Wood could design big too. In the 1890s he proposed a façade for the new building of Whitworth Art Gallery which would have been 26 bays wide, roughly equivalent to Manchester Town Hall.

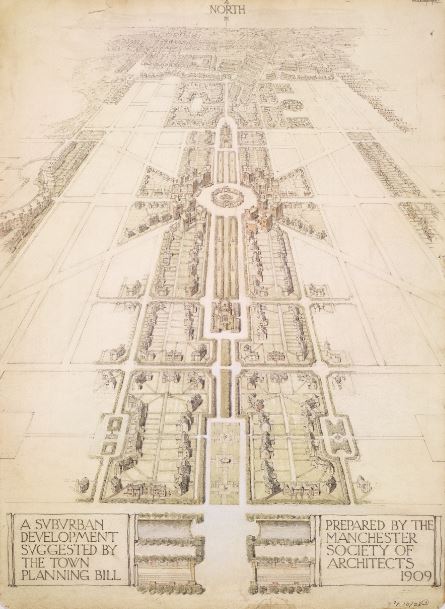

But his grandest design would have transformed part of Manchester and transformed it gloriously with a capital G. During research for a new book Lost & Imagined Manchester, coming out this week, I came across a scheme by Wood that if it had been built and somehow survived would have made excursions to Port Sunlight from Manchester redundant. This would have been the garden village/model village par excellence for the North of England, indeed, of anywhere in the country, complete with art gallery, public baths, meeting hall, extensive gardens, fountains, churches and a school.

It would have covered a huge area between Platt Fields Park and Alexandra Park and was commissioned by Manchester Society of Architects in 1909 following the Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1909. The latter banned back-to-back housing and imposed certain standards on house building. It also encouraged garden suburbs following the pioneering work of Ebeneezer Howard at Letchworth Garden City.

Wood's genius: (looking North) The tourist attraction and living space we never built

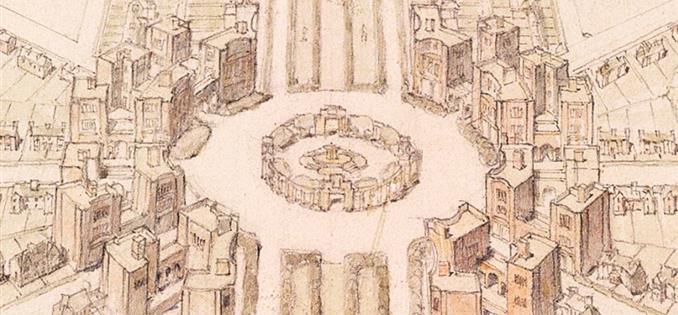

Wood's genius: (looking North) The tourist attraction and living space we never built Wood's genius. the southern part of the development with the public buildings

Wood's genius. the southern part of the development with the public buildingsThe level of drawn detail on the proposal around the main central avenue is very high but whether this was anything but a proposal, a testing of the water so to speak, is unclear. Manchester shortly after delivered garden suburbs at Chorltonville and Burnage under private ownership and ultimately in the vast acres of Wythenshawe under city ownership. After WWII suburban council estates proliferated which have ultimately proved socially dubious.

But this Wood design would have been the bee’s knees, the icing on the cake: a work of art covering many acres from Claremont Road to beyond Wilbraham Road in what was then Withington Urban District Council.

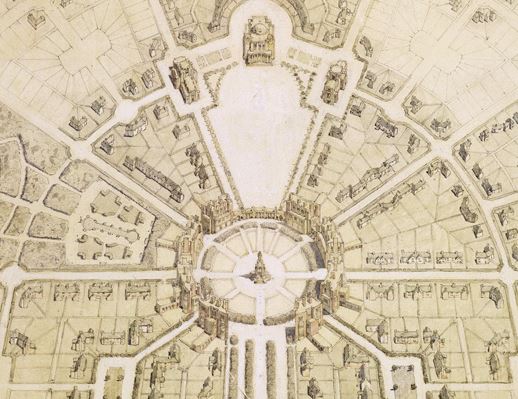

The design was delivered at a time when Wood was working with James Henry Sellers who introduced him to the new type of ‘cubic’ architecture using reinforced concrete to create buildings with shapes freed from the demands of say a traditional pitched roof. Wood’s work as a consequence, while never losing its attention to detail, lost some of its picturesque nature but gained a different type of punch.

You can see the images here how that delightful ‘circle’ of flat roofed, modernist houses and apartments, resembling Wood and Sellers’ (mainly Sellers’) work at Elm Street School the year before. These surround a garden surrounded by a colonnade containing a fountain.

Wood's genius: as modern as it gets for the time

Wood's genius: as modern as it gets for the timeWood came into a fortune upon his father’s death in 1909. He no longer needed to work so he applied himself less and less to architecture. He eventually retired to Mussolini’s Italy (an odd choice for a man who had been left of centre politically all his life but then again Italy is never an odd choice for an aesthete) and lived out his life at Monte Calvario Imperia close to the French border on the Italian Riviera. He died in 1935.

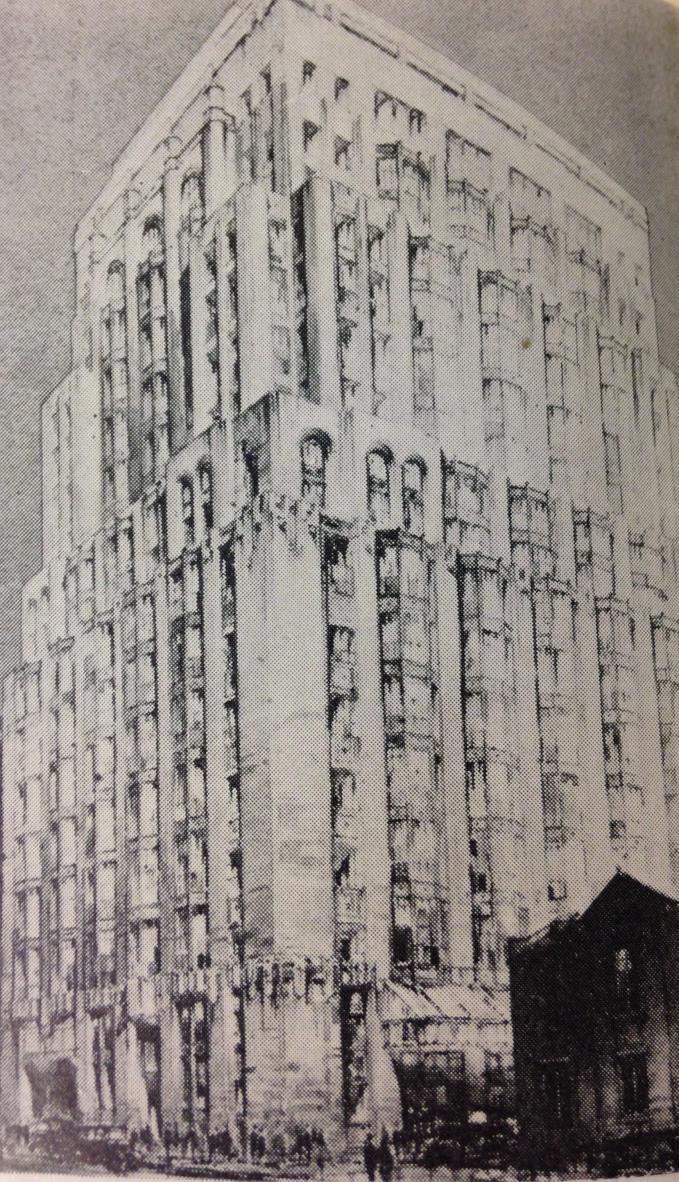

There was time for one last heroic flourish that would have delivered that grand city centre building. Lee House, Great Bridgewater Street, Manchester (1931) is an eight storey building that should have been seventeen storeys. Although credited to the firm of Harry S Fairhurst, it was, says Morris, ‘designed by Sellers with assistance from Wood, in their earlier art deco styling. Brick pilasters, broad at the corners, run the full height of the structure, alternating with canted bronze windows subdivided into ‘leaded lights’ (now replaced). The piers and corners were subtly highlighted using recessed mouldings, and the ground floor and top were faced in Portland stone with art deco ornament. Had it been completed, Lee House would have been one of the highest buildings in Europe and is a fitting climax to the unique architectural partnership of Wood and Sellers.’

Lee House - just half way there

Lee House - just half way there Full height Lee

Full height LeeMorris is part of the Edgar Wood Society based in Middleton. So is Nick Baker, both part of a team fighting the good fight to keep the flame of this remarkable man and artist burning.

Baker says: "Edgar Wood's importance lies in his unique and compelling contribution to the fertile European and North American architectural scene at the turn of the twentieth century. It is arguable that, aside from Scotland’s Charles Rennie Mackintosh, no other British architect’s work was so consistently laced with restless, avant garde progression as that of Wood."