Jonathan Schofield takes an occasional look at some of the streets that have gone or totally changed

Cannon Street starts life more than 200 years ago as a minor street and ends as perhaps the ugliest thoroughfare to afflict this country. What comes down to us though, are lots of interesting stories and one of my favourite photographs, largely because it looks on the face of it so mundane.

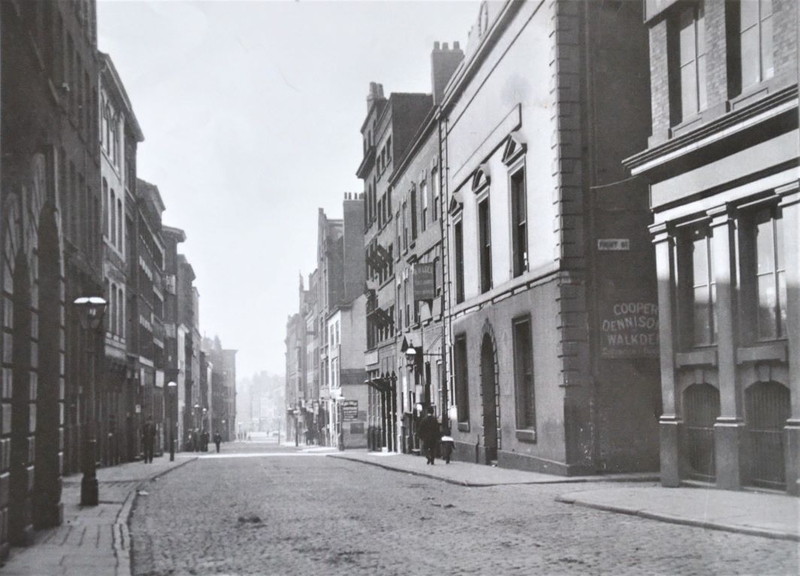

The photograph below from Friday 10 May, 1907, by T Baddeley, is wonderful precisely because of its anonymity.

It captures a typical early morning scene in the city centre of Edwardian Manchester. Cannon Street can be seen receding down from High Street towards what is presently Exchange Square. There is a bobby on the beat, on his own, walking towards the camera, possibly dreaming of the day when he can charge around in one of those new motor vehicles he’s recently seen tootling about the city.

More charmingly on the right is a father and child, hand in hand, the man sporting a bowler and the child seemingly dressed in something akin to a sailor’s uniform. Let’s hope they are enjoying a happy stroll, dad being daft and the child giggling at his silliness. Let's hope for them this was a good day.

After widening and damage in World War II, all trace of old Cannon Street was finally removed as the Arndale Centre emerged in the 1970s

The street had been built on what was previously open land from the middle of the eighteenth century and several Georgian period properties survived until 1907.

The father and child are walking past Cannon Street Independent Chapel, one of the first buildings to arrive from 1760. At the rear of the building there were several tombs. The last interment had been that of Dugal Mann, tape manufacturer, in 1788. The building closed as chapel around 1860, by which its congregation had long disappeared from the city centre. In this picture the property has become an ink factory for Cooper, Dennison and Walkden. The alleyway meeting Cannon Street here is called, aptly, Print Street.

Next down Cannnon Street, on the right here, is a fine eighteenth century townhouse converted into RW Lees, tailors. Then comes a building which displays a once commonplace now extinct feature of industrialised Manchester. The building is nineteenth century and commercial, maybe the workshop of Lees, the tailors, or maybe a general warehouse. Either way, the windows carry reflector boards, effectively cheap mirrors placed at an angle on the outside of the window to throw extra light into the rooms behind. These would have been such a familiar sight in the warehouse districts of Manchester no-one would have thought to mention them.

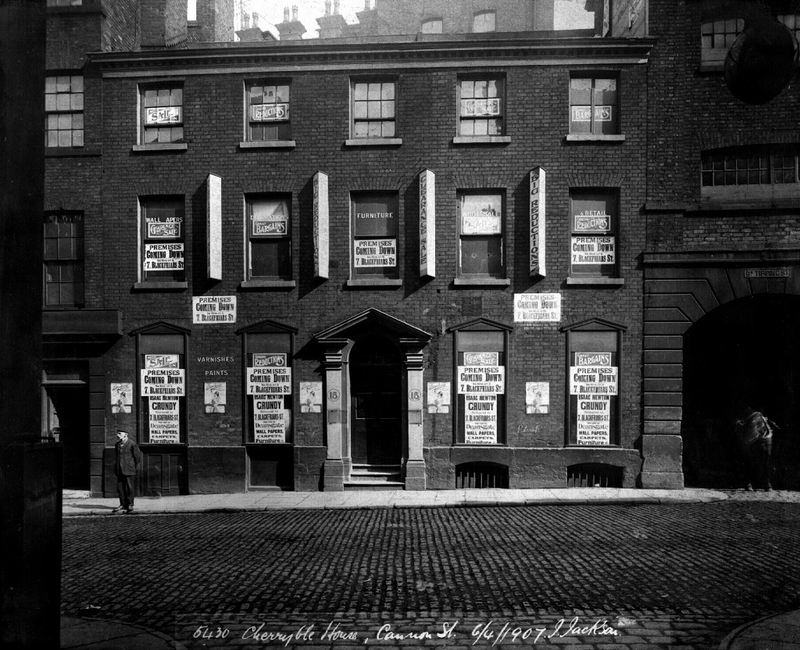

As our dad and son heroes continue down the street they will pass a doomed eighteenth century house converted into commercial use. In 1907 demolition signs have been stuck to the windows (pictured above). This had been the townhouse of the Grant brothers in the early nineteenth century. The Grants had their factories in Ramsbottom, as the Grants Arms Hotel in that fine Pennine town reminds us.

Charles Dickens incorporated the brothers into his novel Nicholas Nickleby but gave them the name of Cheeryble. They were the opposite of the miserable penny pinchers Scrooge and Gradgrind which Dickens would feature in A Christmas Carol and Hard Times respectively. The Cheerybles were kindly, benevolent, philanthropic, and as their name suggests, cheerful.

A newspaper report of 1907 reads:

'‘Great clearance sale, premises coming down’. These are the words on the placard pasted on the outer walls of Cheeryble House, in Cannon Street. With the exception of a few slight internal alterations, the house stands today as it did when Dickens described it. It has the carved old oak staircase leading to the upper and domestic part of the premises. They are at present in the occupation of Isaac Newton Grundy, a firm of linoleum merchants. The necessity for the abolition (of the building) has been brought through the Corporation scheme for widening the streets. In a recent interview one of the partners said that lovers of Dickens came from all parts of the world to inspect the old place and he had been offered large prices, especially by American tourists, for relics of it.'

Someone, somewhere must still have some of those ‘relics’ because they were certainly removed before the demolition. After widening and damage in World War II, all trace of old Cannon Street was finally removed as the Arndale Centre emerged in the 1970s. A new Cannon Street emerged as the ugliest street in Britain, a canyon of yellow tile and exhaust fumes, hosting the main bus station.

Following the IRA’ bomb of 1996 the Arndale was remodelled and the bus station and the street disappeared. Thus, the name Cannon Street was permanently expunged from history as completely as the identity of a father and child in a late spring sunshine walking down a hill, the sun shining, the day ahead of them, the future unknown.